Joel Whitney at Public Books:

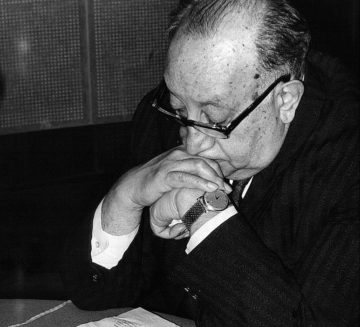

“Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” explained Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1973.

“Our Latin American literature has always been a committed, a responsible literature,” explained Guatemalan novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias in 1973.

The great works of our countries have been written in response to a vital need, a need of the people, and therefore almost all our literature is committed. Only as an exception do some of our writers isolate themselves and become uninterested in what is happening around them; such writers are concerned with psychological or egocentric subjects and the problems of a personality out of contact with surrounding reality.

It is the bourgeois writers, he wants to say here, who ignore the looting of their resources by the rich behemoth to the north, which then turns around and redeploys those riches on death squads and dictators. It is no surprise, then, that Asturias’s landmark novel, Mr. President, confronts its readers with similar frankness. Mr. President examines widespread corruption around a fictional Guatemalan dictator. But its 1946 debut reflected a delay of more than a decade by the country’s real dictators, who disrupted the novel’s genesis and sent its author into exile. And in this act of suppression, Asturias’s censors and exilers were aided by the US, specifically the CIA.

Such suppression has long impaired Asturias’s career, reputation, and recognition. Indeed, in a new introduction to Mr. President—out last summer in David Unger’s lucid new translation—literary scholar Gerald Martin calls the novel “the first page of the Boom.” “The Boom” was the nickname for a clutch of new Latin American novels emerging in the 1960s, including those by future Nobel laureates Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa.

More here.