Category: Recommended Reading

Serious Clowning: Satirist David Sedaris on life, death and his latest collection of essays

Lou Fencher in EBX:

His father set a number of things in place so that after death “there would be little bombs that would explode upon me,” Sedaris tells me. “Like when I graduated from college, he said he’d set up an IRA for me and talked for years about it. You know, he never set it up. And he left me the minimum amount of money you can leave somebody so they wouldn’t contest the will. When I found out about it and confronted him, that was his big disappointment, that I’d found out before he died. It was also in his will that I would get any boats or cars that he owned. We’d never had a boat and I don’t even know how to drive. My father took pains to sell his 1964 mint-condition Porsche a year before he died just so I wouldn’t get it. It’s nasty things, hurtful things. I’m not hurting for money, but it’s not about that. It bothers me that I’m allowing him to hurt me. Everyone else in my family is getting two-and-a-half million dollars. If he had left me that two-and-a-half million dollars, I’d probably be thinking, you know, he’s not so bad, maybe I just misunderstood him. But to have been treated that way in life and then in death as well? I feel pathetic being a 65-year-old man whining because his father wasn’t nice. And then it bothers me that I’m being pathetic.”

His father set a number of things in place so that after death “there would be little bombs that would explode upon me,” Sedaris tells me. “Like when I graduated from college, he said he’d set up an IRA for me and talked for years about it. You know, he never set it up. And he left me the minimum amount of money you can leave somebody so they wouldn’t contest the will. When I found out about it and confronted him, that was his big disappointment, that I’d found out before he died. It was also in his will that I would get any boats or cars that he owned. We’d never had a boat and I don’t even know how to drive. My father took pains to sell his 1964 mint-condition Porsche a year before he died just so I wouldn’t get it. It’s nasty things, hurtful things. I’m not hurting for money, but it’s not about that. It bothers me that I’m allowing him to hurt me. Everyone else in my family is getting two-and-a-half million dollars. If he had left me that two-and-a-half million dollars, I’d probably be thinking, you know, he’s not so bad, maybe I just misunderstood him. But to have been treated that way in life and then in death as well? I feel pathetic being a 65-year-old man whining because his father wasn’t nice. And then it bothers me that I’m being pathetic.”

More here.

Richard Sherman (1928 – 2024) Songwriter

Barry Kemp (1940 – 2024) Archaeologist And Egyptologist

Doug Ingle (1945 – 2024) Musician And Founder of Iron Butterfly

Saturday, June 1, 2024

Fanon the Universalist

Susan Neiman in The New York Review of Books:

Decolonization, said Frantz Fanon, began a new chapter of history. It’s common enough for the politically engaged to magnify their engagement, if only to sustain themselves through the cycles of danger and boredom that accompany serious political struggle, but in this case Fanon might have understated things. Stronger nations have overtaken weaker ones since the beginning of recorded history—indeed, since before there were nations in our sense at all. Contrary to much current opinion, colonialism did not begin with the Enlightenment, whose ideas were later twisted to support it.

Until the last century imperialism was as universal a political practice as any: the Romans and the Chinese created empires, as did the Assyrians, the Aztecs, the Malians, the Khmer, the Mughals, and the Ottomans, to name just a few. Those empires operated with different degrees of brutality and repression, but all presupposed the logic recorded in Thucydides’ dialogue between the Athenians and the Melians: big states swallow little ones as night follows day. It’s a law of nature against which reason has no claim.

Enlightenment philosophers asked whether such assumptions really are as natural as alleged, and they used their reason to ground a thoroughgoing attack on colonialism. Kant congratulated the Chinese and the Japanese for their wisdom in refusing entry to “unjust invaders”; Diderot urged the “Hottentots” to let their arrows fly toward the Dutch East India Company. Like progressive intellectuals in our day, these thinkers had limited political success, at least in the short term: the colonial projects they condemned only expanded in the nineteenth century. Pace the ambivalent American experiment, it wasn’t until the twentieth century that Enlightenment ideals about universal human rights began to undergird real anticolonial struggles from Ireland to India.

More here.

How Israel’s Illiberal Democracy Became a Model for the Right

Suzanne Schneider in Dissent:

Amid the mass slaughter and starvation of Palestinians in Gaza, it is easy to forget the political drama that gripped Israel only one year ago. After assuming power in December 2022, a new far-right government led by Benjamin Netanyahu had proposed a slate of judicial and administrative reforms that prompted a wave of anti-government protests. Concerned journalists, former U.S. and Israeli government officials, and major American Jewish organizations issued ominous warnings about democratic backsliding. Israel, it seemed, was heading in the direction of illiberal Hungary.

This framing was never quite convincing. While hundreds of thousands of Israelis marched to save democracy, most refused to address, or even acknowledge, the occupation. A country that maintains an unequal citizenship system for Jewish and Palestinian Israelis—and disenfranchises approximately 35 percent of the population in territory it controls on account of their ethnic identity—does not match the conventional definition of democracy. But there is an alternative idea of democracy in vogue among partisans of the global right, one built around the right to discriminate and to privilege the needs of the nation over those of individuals in general and minorities in particular. It is this version of democracy that has long prevailed in Israel, and which the Jewish state’s supporters now offer as a blueprint for illiberal leaders around the world.

Aided by new institutional networks that spur the circulation of right-wing ideas and practices among Israeli, Hungarian, and American conservatives, the Zionist right has acquired ideological heft and global recognition by joining the legal right to discriminate to a defense of national particularism, tradition, and other “conservative values.” The champions of illiberal democracy claim to represent a venerable alternative to both liberalism and fascism; their political vision is more accurately described as ethno-authoritarian. One problem, as Israelis began to experience during last year’s crackdown on anti-government protests, is that states built around eliminating enemies of the people eventually tend to devour their own.

More here.

Meaning & Knowledge – Ernest Nagel (1966)

Nostalgia: A History of a Dangerous Emotion

Matthew Reisz at The Guardian:

While neuroscientists sometimes treat emotions as human universals, historians are keen to show how the words we use to describe our feelings, and indeed the feelings themselves, change with the times. “Nostalgia was one of the most studied medical conditions of the 19th century,” Arnold-Forster explains, believed to cause “palpitations and unexplained ruptures in the skin” as well as depression and disturbed sleep. It was first diagnosed among 17th-century Swiss mercenaries and referred to “a kind of pathological patriotic love, an intense and dangerous homesickness”. (Since sufferers were assumed to be missing the pure mountain air, one doctor suggested they should be put in tall towers to recuperate.) It was not until the early 20th century that homesickness and nostalgia in the current sense began to be seen as distinct.

Yet it continued to be treated as rather suspect. In the mid-20th century, a psychoanalyst called Nandor Fodor dismissed nostalgia, along with utopian politics and even the vogue for Tarzan films, as “the manifestation of a latent desire to return to the womb”.

more here.

Life In The Era Of Practical Magic

Liesl Schillinger at the NYT:

In her spirited and richly detailed “Cunning Folk,” Tabitha Stanmore, a specialist in medieval and early modern magic, writes that between the 14th and 17th centuries, “a whole host of magical practitioners” pervaded villages, cities and royal courts — diviners, astrologers, charm makers, healers. Their customers were commoners and courtiers, peasants and merchants, housewives and queens.“This book is not about witches,” Stanmore emphasizes. The cunning folk were different, she explains, because they used “service magic,” not the dark arts, “to positively affect the world around them.” What’s more, “most people” marked a “distinction” between magicians of this kind (good, basically) and witches (evil), although the boundary, she admits, could be “fluid.” That’s because their clients’ requests could be “sinister,” to put it mildly. In 1613, for instance, the depraved Countess of Essex (later imprisoned for murdering a foe with a toxic enema) requested a slow-acting poison from a fortuneteller named Mary Woods, so she could bump off the Count. Woods skipped town rather than comply (so she told authorities) but was tried anyway; her fate is unknown.

In her spirited and richly detailed “Cunning Folk,” Tabitha Stanmore, a specialist in medieval and early modern magic, writes that between the 14th and 17th centuries, “a whole host of magical practitioners” pervaded villages, cities and royal courts — diviners, astrologers, charm makers, healers. Their customers were commoners and courtiers, peasants and merchants, housewives and queens.“This book is not about witches,” Stanmore emphasizes. The cunning folk were different, she explains, because they used “service magic,” not the dark arts, “to positively affect the world around them.” What’s more, “most people” marked a “distinction” between magicians of this kind (good, basically) and witches (evil), although the boundary, she admits, could be “fluid.” That’s because their clients’ requests could be “sinister,” to put it mildly. In 1613, for instance, the depraved Countess of Essex (later imprisoned for murdering a foe with a toxic enema) requested a slow-acting poison from a fortuneteller named Mary Woods, so she could bump off the Count. Woods skipped town rather than comply (so she told authorities) but was tried anyway; her fate is unknown.

more here.

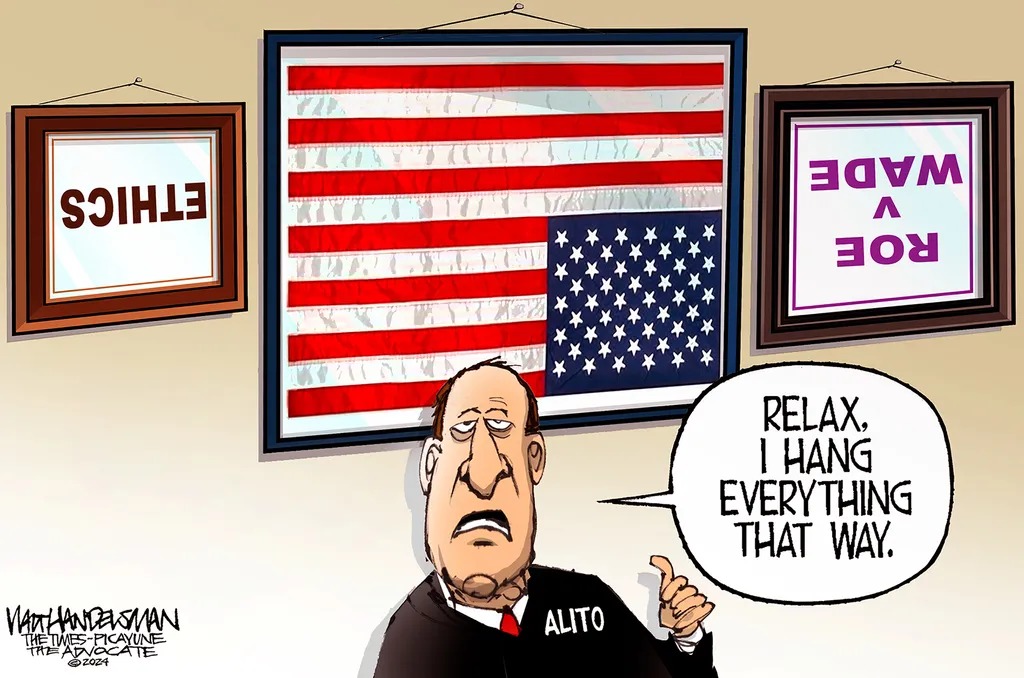

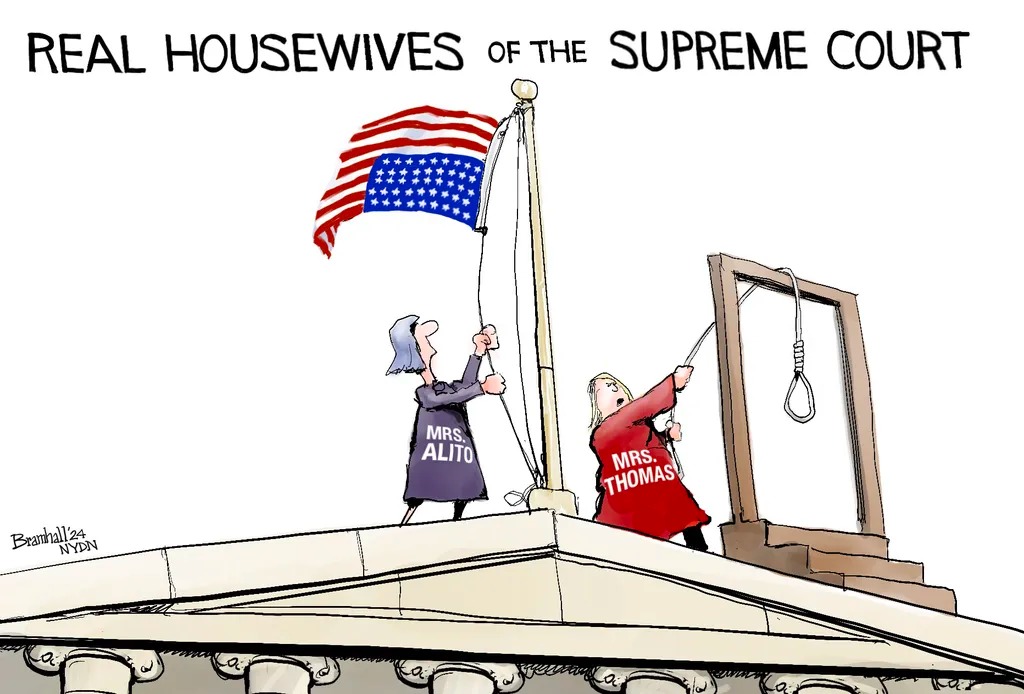

Justice Alito’s flag etiquette

From TheWeek:

Are Deadly Recalls Rising?

Anna Skinner in Newsweek:

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already issued 519 Class 1 recalls so far this year, fueling concerns from Americans that deadly recalls are on the rise. A Class 1 recall is “a situation in which there is a reasonable probability that the use of or exposure to a violative product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death,” according to the FDA’s website. When examining weekly data for Class 1 recalls through May for the past four years, the products listed most frequently were in the drug, food and medical device categories.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already issued 519 Class 1 recalls so far this year, fueling concerns from Americans that deadly recalls are on the rise. A Class 1 recall is “a situation in which there is a reasonable probability that the use of or exposure to a violative product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death,” according to the FDA’s website. When examining weekly data for Class 1 recalls through May for the past four years, the products listed most frequently were in the drug, food and medical device categories.

Learning that consuming a recalled product can have fatal consequences is disconcerting, but Americans can be at ease that deadly recalls don’t appear to be on the rise. According to the FDA data, in 2023 there were 729 Class 1 recalls through May, more than 200 above the current number for this year. The majority of the 2023 recalls occurred during the week of March 22, when 410 recalls were issued. There were 538 Class 1 recalls through May in 2022, according to the FDA website. In fact, the last time there were less deadly recalls through May than this year was in 2021, when there were only 308 Class 1 recalls. Newsweek reached out to the FDA by email for comment.

More here.

Friday, May 31, 2024

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megabudget New Movie Is a Journey Into the Heart of Madness

Sam Adams in Slate:

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis took 41 years to make. It might take as long to understand. Coppola’s magnum opus, which premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival last night, is a movie of extraordinary highs and baffling lows, alternately dazzling and confounding. Sometimes, in the same moment, it’s both. When I asked colleagues who’d seen it—at a remote early-morning screening, added at the last minute to accommodate Coppola’s preference for IMAX—they looked at me like the mute humans in the Planet of the Apes movies, as if their powers of speech had abruptly and unexpectedly deserted them. No one wants to trash an elderly legend’s passion project, one that, after decades of trying and failing to get it made, he finally financed with some $120 million of his own money—not to mention one that is dedicated to his late wife, Eleanor, who died last month. But it’s also a film that defies and even actively resists description, one that sounds even loopier in summary than its 138 minutes feel. You have to see it to believe it. And even then, you may not.

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis took 41 years to make. It might take as long to understand. Coppola’s magnum opus, which premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival last night, is a movie of extraordinary highs and baffling lows, alternately dazzling and confounding. Sometimes, in the same moment, it’s both. When I asked colleagues who’d seen it—at a remote early-morning screening, added at the last minute to accommodate Coppola’s preference for IMAX—they looked at me like the mute humans in the Planet of the Apes movies, as if their powers of speech had abruptly and unexpectedly deserted them. No one wants to trash an elderly legend’s passion project, one that, after decades of trying and failing to get it made, he finally financed with some $120 million of his own money—not to mention one that is dedicated to his late wife, Eleanor, who died last month. But it’s also a film that defies and even actively resists description, one that sounds even loopier in summary than its 138 minutes feel. You have to see it to believe it. And even then, you may not.

More here.

Lessons From a Mass Shooter’s Mother

Mark Follman at Mother Jones:

A decade has passed, but exhuming Elliot Rodger’s life and ghastly final actions remains fraught. It risks inflicting further pain for the victims’ families and other survivors, and new revelations could feed the kind of infamy many perpetrators seek. The case stands out among the hundreds I’ve studied in 12 years of reporting on mass shootings. To this day it fuels copycat attackers who fixate on misogyny, making it an ongoing subject of news coverage and various academic and security research. It also helped catalyze policy change, in particular the spread of “red flag” laws aimed at keeping guns away from unstable people.

A decade has passed, but exhuming Elliot Rodger’s life and ghastly final actions remains fraught. It risks inflicting further pain for the victims’ families and other survivors, and new revelations could feed the kind of infamy many perpetrators seek. The case stands out among the hundreds I’ve studied in 12 years of reporting on mass shootings. To this day it fuels copycat attackers who fixate on misogyny, making it an ongoing subject of news coverage and various academic and security research. It also helped catalyze policy change, in particular the spread of “red flag” laws aimed at keeping guns away from unstable people.

Yet from the start, this tragedy has been wrongly mythologized in the media and academia and poorly understood by the public, its lessons for prevention buried.

More here.

“Mera Piya Ghar Aaya” recital by Fareed Ayaz & Abu Muhammad Qawwal & Brothers

The Indian Election and the Country’s Economic Future

Raghuram G. Rajan at Project Syndicate:

There is a buzz in India today – a sense of limitless possibilities. India has just overtaken its former colonial master (the United Kingdom) to become the world’s fifth-largest economy. If it maintains its current growth rate of 6-7% per year, it will soon overtake stagnant Japan and Germany to take over third place.

There is a buzz in India today – a sense of limitless possibilities. India has just overtaken its former colonial master (the United Kingdom) to become the world’s fifth-largest economy. If it maintains its current growth rate of 6-7% per year, it will soon overtake stagnant Japan and Germany to take over third place.

But by 2050, India’s workforce will start shrinking, owing to demographic aging. Growth will slow. That means India has only a narrow window in which to grow rich before it grows old: with per capita income of just $2,500, the economy must grow by 9% per year for the next quarter-century. That is an extremely difficult task, and the current election may well determine whether it remains possible at all.

More here.

Twilight | ContraPoints

Wittgenstein And Buster Keaton

Robert Goff at Lawrence Weschler’s Wondercabinet:

Now we may return briefly to the philosophy of Wittgenstein. If this seems a radical change of subject, an abrupt passage from the familiarity of comedy to the strangeness of technical philosophy, then it may be hoped that such an experience of difference may itself become important. Instead of connecting Keaton to Wittgenstein in some difficult conceptual fashion, I would be happy {great exact use of the word!} simply to convey the impression that in the same way as Keaton may be profound, Wittgenstein may be enjoyable. The relation between them could turn out to be something more interesting than the necessity to choose between comedy and philosophy.

Now we may return briefly to the philosophy of Wittgenstein. If this seems a radical change of subject, an abrupt passage from the familiarity of comedy to the strangeness of technical philosophy, then it may be hoped that such an experience of difference may itself become important. Instead of connecting Keaton to Wittgenstein in some difficult conceptual fashion, I would be happy {great exact use of the word!} simply to convey the impression that in the same way as Keaton may be profound, Wittgenstein may be enjoyable. The relation between them could turn out to be something more interesting than the necessity to choose between comedy and philosophy.

Although Wittgenstein once said it would be possible to have a significant philosophical work composed entirely of jokes, almost no one writing about his philosophy has found humor there. He is generally taken to be difficult, technical, obscure, and not funny. It is an uneasy reputation for someone whose thought keeps returning to a comparison between language and game play.

more here.

Adorno’s Aesthetics

Owen Hatherley at the London Review of Books:

Adorno is easily parodied. Photos on social media show him frog-like, myopic and bald, denouncing the willing consumption of dross, the personal embodiment of a refusal to ‘let people enjoy things’. Another meme features Reverend Lovejoy from The Simpsons derisively brandishing a copy of Minima Moralia: ‘You ever sat down and read this thing?’ (In the original, it’s the Bible the reverend is holding up to ridicule.) Others use an image of Adorno in a one-piece swimsuit at the beach, looking as if he’s quietly enjoying himself – a more winsome George Costanza. These memes are surely made by people who had to study Adorno at university. They will probably have read the depressive aphorisms of Minima Moralia and some fragments from Dialectic of Enlightenment on the ‘culture industry’; a few unfortunates will have had to tackle the thickets of Aesthetic Theory or Negative Dialectics. Along with the parodies come received ideas: Adorno the grouch, Adorno the scourge of mass media, Adorno the mandarin Marxist; or, as Ben Watson puts it in his counterweight, Adorno for Revolutionaries (2011), Adorno as ‘a kind of German T.S. Eliot without the practical cats’.

Adorno is easily parodied. Photos on social media show him frog-like, myopic and bald, denouncing the willing consumption of dross, the personal embodiment of a refusal to ‘let people enjoy things’. Another meme features Reverend Lovejoy from The Simpsons derisively brandishing a copy of Minima Moralia: ‘You ever sat down and read this thing?’ (In the original, it’s the Bible the reverend is holding up to ridicule.) Others use an image of Adorno in a one-piece swimsuit at the beach, looking as if he’s quietly enjoying himself – a more winsome George Costanza. These memes are surely made by people who had to study Adorno at university. They will probably have read the depressive aphorisms of Minima Moralia and some fragments from Dialectic of Enlightenment on the ‘culture industry’; a few unfortunates will have had to tackle the thickets of Aesthetic Theory or Negative Dialectics. Along with the parodies come received ideas: Adorno the grouch, Adorno the scourge of mass media, Adorno the mandarin Marxist; or, as Ben Watson puts it in his counterweight, Adorno for Revolutionaries (2011), Adorno as ‘a kind of German T.S. Eliot without the practical cats’.

Adorno’s aesthetics are extreme. ‘He is an easy man to caricature,’ Watson writes, ‘because he believed in exaggeration as a means of telling the truth.’ But he was no misanthrope.

more here.

Friday Poem

“ Many American men . . . do not have enough awakened

or living warriors inside to defend their soul houses.”

…………………………………………………………. —Robert Bly

Old Self

I chanced across my old self

today. I was sitting in the second

floor office where I used to work —

at the typewriter, young, thin guy,

in his late 20’s, white shirt, narrow

dark tie, serious demeanor, writing

as essay against the Vietnam war.

I came up the stairs and saw him —

a decent human being, diligent,

not remotely aware of the ambush

life had waiting — not knowing

he’d permit himself to be taken

prisoner then, in confusion,

do desperate things, betray

what he loved — and that nothing

would enable him to survive

as he was.

I passed the open door

and wanted to cry out — warn him,

force the warriors to raise

their spears. But even hearing

my shout, he would have only

hesitated, then turned back to

his devoted, lonely interminable

work.

by Lou Lipsitz

from Seeking the Hook

Signal Books, 1997