Category: Recommended Reading

What If Motherhood Isn’t Transformative at All?

Anastasia Berg in The Cut:

To have a child, it is often said, is to transform one’s identity. What this might have meant in the past is more or less obvious: With few exceptions, for the better part of history, to have a child meant it was time for a woman to say her final farewells to whatever public existence she managed to forge up to that point. But now there is another, more mysterious change that becoming a mother is understood to imply, more basic than the historical conditions of oppression. This change is supposed to reconfigure the deepest core of one’s being. When the contemporary analytic philosopher L. A. Paul wanted to introduce the idea of a fundamentally transformative experience, one of her central examples was having a child. For women, especially, becoming a parent is frequently described as a total revolution of the self. “Giving birth to a baby is, literally, splitting in two, and it is not always clear which one your ‘I’ goes with,” philosopher Agnes Callard wrote in a reflection on the relief she felt after losing an unplanned pregnancy.

To have a child, it is often said, is to transform one’s identity. What this might have meant in the past is more or less obvious: With few exceptions, for the better part of history, to have a child meant it was time for a woman to say her final farewells to whatever public existence she managed to forge up to that point. But now there is another, more mysterious change that becoming a mother is understood to imply, more basic than the historical conditions of oppression. This change is supposed to reconfigure the deepest core of one’s being. When the contemporary analytic philosopher L. A. Paul wanted to introduce the idea of a fundamentally transformative experience, one of her central examples was having a child. For women, especially, becoming a parent is frequently described as a total revolution of the self. “Giving birth to a baby is, literally, splitting in two, and it is not always clear which one your ‘I’ goes with,” philosopher Agnes Callard wrote in a reflection on the relief she felt after losing an unplanned pregnancy.

More here.

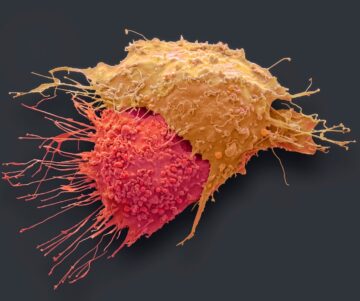

We Must Find Ways to Detect Cancer Much Earlier

The Oncology Think Tank in Scientific American:

“Everyone here has the sense that right now is one of those moments when we are influencing the future.” —Steve Jobs

Every year, cancer kills approximately 10 million people worldwide. Of those who die, two thirds do so because they were diagnosed with advanced disease. A new paradigm in the approach to cancer is overdue. COVID-19 has already altered conversations and expectations within the medical community and is forcing a rethinking of many public health issues.

Every year, cancer kills approximately 10 million people worldwide. Of those who die, two thirds do so because they were diagnosed with advanced disease. A new paradigm in the approach to cancer is overdue. COVID-19 has already altered conversations and expectations within the medical community and is forcing a rethinking of many public health issues.

Friday Poem

The Second Coming

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

W.B. Yeats

from The Dial, 1920

Thursday, June 13, 2024

3QD Is Looking For New Columnists: LAST WEEK!

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

Here’s your chance to say what you want to the large number of highly educated readers that make up 3QD’s international audience. Several of our regular columnists have had to cut back or even completely quit their columns for 3QD because of other personal and professional commitments and so we are looking for a few new voices. We do not pay, but it is a good chance to draw attention to subjects you are interested in, and to get feedback from us and from our readers.

We would certainly love for our pool of writers to reflect the diversity of our readers in every way, including gender, age, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, etc., and we encourage people of all kinds to apply. And we like unusual voices and varied viewpoints. So please send us something. What have you got to lose? Click on “Read more” below…

NEW POSTS BELOW

Why introductory economics courses continued to teach zombie ideas from before economics became an empirical discipline

Walter Frick in Aeon:

What happens to the job market when the government raises the minimum wage? For decades, higher education in the United States has taught economics students to answer this question by reasoning from first principles. When the price of something rises, people tend to buy less of it. Therefore, if the price of labour rises, businesses will choose to ‘buy’ less of it – meaning they’ll hire fewer people. Students learn that a higher minimum wage means fewer jobs.

What happens to the job market when the government raises the minimum wage? For decades, higher education in the United States has taught economics students to answer this question by reasoning from first principles. When the price of something rises, people tend to buy less of it. Therefore, if the price of labour rises, businesses will choose to ‘buy’ less of it – meaning they’ll hire fewer people. Students learn that a higher minimum wage means fewer jobs.

But there’s another way to answer the question, and in the early 1990s the economists David Card and Alan Krueger tried it: they went out and looked. Card and Krueger collected data on fast-food jobs along the border between New Jersey and Pennsylvania, before and after New Jersey’s minimum wage increase. The fast-food restaurants on the New Jersey side of the border were similar to the ones on the Pennsylvania side in nearly every respect, except that they now had to pay higher wages. Would they hire fewer workers in response?

‘The prediction from conventional economic theory is unambiguous,’ Card and Krueger wrote. It was also wrong.

More here.

Why Sharks Matter

Leon Vlieger at The Inquisitive Biologist:

When it comes to protecting animal species, you would think that conservation biologists, environmental advocates, and animal-loving members of the public are all on the same page. However, in Why Sharks Matter, marine biologist David Shiffman shows that this is not always the case. Though there are plenty of books marvelling at sharks, this, to my knowledge, is the first one to provide an informed and informative look at shark conservation. Frank, frequently opinionated, and full of refreshingly counterintuitive ideas, Why Sharks Matter is an eye-opener that delivered far more than I expected based on the title.

When it comes to protecting animal species, you would think that conservation biologists, environmental advocates, and animal-loving members of the public are all on the same page. However, in Why Sharks Matter, marine biologist David Shiffman shows that this is not always the case. Though there are plenty of books marvelling at sharks, this, to my knowledge, is the first one to provide an informed and informative look at shark conservation. Frank, frequently opinionated, and full of refreshingly counterintuitive ideas, Why Sharks Matter is an eye-opener that delivered far more than I expected based on the title.

More here.

Inside Mexico’s anti-avocado militias

Alexander Sammon in The Guardian:

Michoacán, where about four in five of all avocados consumed in the United States are grown, is the most important avocado-producing region in the world, accounting for nearly a third of the global supply. This cultivation requires a huge quantity of land – much of it found beneath native pine forests – and an even more startling quantity of water. It is often said that it takes about 12 times as much water to grow an avocado as it does a tomato. Recently, competition for control of the avocado, and of the resources needed to produce it, has grown increasingly violent, often at the hands of cartels. A few years ago, in nearby Uruapan, the second-largest city in the state, 19 people were found hanging from an overpass, piled beneath a pedestrian bridge, or dumped on the roadside in various states of undress and dismemberment – a particularly gory incident that some experts believe emerged from cartel clashes over the multibillion-dollar trade.

Michoacán, where about four in five of all avocados consumed in the United States are grown, is the most important avocado-producing region in the world, accounting for nearly a third of the global supply. This cultivation requires a huge quantity of land – much of it found beneath native pine forests – and an even more startling quantity of water. It is often said that it takes about 12 times as much water to grow an avocado as it does a tomato. Recently, competition for control of the avocado, and of the resources needed to produce it, has grown increasingly violent, often at the hands of cartels. A few years ago, in nearby Uruapan, the second-largest city in the state, 19 people were found hanging from an overpass, piled beneath a pedestrian bridge, or dumped on the roadside in various states of undress and dismemberment – a particularly gory incident that some experts believe emerged from cartel clashes over the multibillion-dollar trade.

More here.

John Allen Paulos: Avoiding Innumeracy

American cricket found a star. He’s a Silicon Valley tech worker

Pranshu Verma in The Washington Post:

A Brief History of Sexism in Medicine

Danielle Friedman in The New York Times:

Six years ago, Dr. Elizabeth Comen, a breast cancer specialist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in Manhattan, held the hand of a patient who was hours from death. As Dr. Comen leaned in for a final goodbye, she pressed her cheek to her patient’s damp face. “Then she said it,” Dr. Comen recalled. “‘I’m so sorry for sweating on you.’” In her two decades as a physician, Dr. Comen has found that women are constantly apologizing to her: for sweating, for asking follow-up questions, for failing to detect their own cancers sooner.

Six years ago, Dr. Elizabeth Comen, a breast cancer specialist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in Manhattan, held the hand of a patient who was hours from death. As Dr. Comen leaned in for a final goodbye, she pressed her cheek to her patient’s damp face. “Then she said it,” Dr. Comen recalled. “‘I’m so sorry for sweating on you.’” In her two decades as a physician, Dr. Comen has found that women are constantly apologizing to her: for sweating, for asking follow-up questions, for failing to detect their own cancers sooner.

“Women apologize for being sick or seeking care or advocating for themselves,” she said during an interview in her office: “‘I’m so sorry, but I’m in pain. I’m so sorry, this looks disgusting.’” These experiences in the exam room are part of what drove Dr. Comen to write “All in Her Head: The Truth and Lies Early Medicine Taught Us About Women’s Bodies and Why It Matters Today.” In it, she traces the roots of women’s tendency to apologize for their ailing or unruly bodies to centuries of diminishment by the medical establishment. It’s a legacy that continues to shape the lives of women patients, she argues.

More here.

Daniel Chamovitz – Are Plants Sentient?

The Life And Death Of Hollywood

Daniel Bessner at Harper’s Magazine:

In 2012, at the age of thirty-two, the writer Alena Smith went West to Hollywood, like many before her. She arrived to a small apartment in Silver Lake, one block from the Vista Theatre—a single-screen Spanish Colonial Revival building that had opened in 1923, four years before the advent of sound in film.

In 2012, at the age of thirty-two, the writer Alena Smith went West to Hollywood, like many before her. She arrived to a small apartment in Silver Lake, one block from the Vista Theatre—a single-screen Spanish Colonial Revival building that had opened in 1923, four years before the advent of sound in film.

Smith was looking for a job in television. She had an MFA from the Yale School of Drama, and had lived and worked as a playwright in New York City for years—two of her productions garnered positive reviews in the Times. But playwriting had begun to feel like a vanity project: to pay rent, she’d worked as a nanny, a transcriptionist, an administrative assistant, and more. There seemed to be no viable financial future in theater, nor in academia, the other world where she supposed she could make inroads.

For several years, her friends and colleagues had been absconding for Los Angeles, and were finding success. This was the second decade of prestige television: the era of Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Homeland, Girls.

more here.

Thursday Poem

Things

What happened is, we grew lonely

living among the things,

so we gave the clock a face,

the chair a back,

the table four stout legs

which will never fatigue.

We fitted our shoes with tongues

as smooth as our own

and hung tongues inside bells

so we could listen

to their emotional language,

and because we loved graceful profiles

the pitcher received a lip

the bottle a long, slender neck.

Even what was beyond us

was recast in our image;

we gave the country a heart,

the storm an eye,

the cave a mouth

so we could pass into safety.

by Lisel Mueller

from Literature and the Writing Process

Prentice Hall, 1999

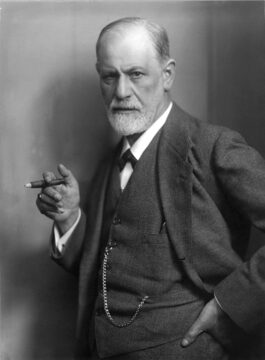

Solving The Riddle Of Sigmund Freud’s Attitude To Death

George Prochnik at the TLS:

The first time Sigmund Freud wrote of destroying his papers he was twenty-one years old. He was writing to Eduard Silberstein, an intimate friend of his youth and the sole other member of the Academia Castellana, a make-believe Spanish literary society anchored in Cervantes trivia, which served them as a secret forum for airing playful fantasies and precocious world-weariness. Freud invited Silberstein to help expunge the record of their relations by conjuring up a pleasant winter evening in which they could come together to burn their archives “in a solemn auto-da-fé”. The next occasion was eight years later, in a letter to his then fiancée Martha Bernays, during what he described as a “bad, barren month”, waiting for money from a chemist to finance further research into cocaine, doing almost nothing except browsing through Russian history and toying with two rabbits who continually nibbled turnips and messed up his floor. His only real accomplishment, he told Martha then, was to have nearly completed his intention of doing something that would dismay various unborn, unfortunate people – namely his future biographers. He’d destroyed all his notes from the past fourteen years, along with correspondence and the original manuscripts of his scientific papers. In 1907, he once again burned a huge trove of private documents. Finally, in 1938, just before escaping Nazified Vienna, he delegated to his daughter Anna the task of overseeing another bonfire of his letters, which she undertook together with his disciple Marie Bonaparte.

The first time Sigmund Freud wrote of destroying his papers he was twenty-one years old. He was writing to Eduard Silberstein, an intimate friend of his youth and the sole other member of the Academia Castellana, a make-believe Spanish literary society anchored in Cervantes trivia, which served them as a secret forum for airing playful fantasies and precocious world-weariness. Freud invited Silberstein to help expunge the record of their relations by conjuring up a pleasant winter evening in which they could come together to burn their archives “in a solemn auto-da-fé”. The next occasion was eight years later, in a letter to his then fiancée Martha Bernays, during what he described as a “bad, barren month”, waiting for money from a chemist to finance further research into cocaine, doing almost nothing except browsing through Russian history and toying with two rabbits who continually nibbled turnips and messed up his floor. His only real accomplishment, he told Martha then, was to have nearly completed his intention of doing something that would dismay various unborn, unfortunate people – namely his future biographers. He’d destroyed all his notes from the past fourteen years, along with correspondence and the original manuscripts of his scientific papers. In 1907, he once again burned a huge trove of private documents. Finally, in 1938, just before escaping Nazified Vienna, he delegated to his daughter Anna the task of overseeing another bonfire of his letters, which she undertook together with his disciple Marie Bonaparte.

more here.

Wednesday, June 12, 2024

When the Mind’s Eye Is Blind

Joshua T. Katz in The Hedgehog Review:

When my daughter was born last year, I was fifty-three years old. I’d wanted a child so badly for so long, and her arrival may well be the most wonderful thing ever to happen to me. And yet I cannot picture her first breath, though I witnessed it from inches away. I also cannot picture her right now, as I type these words. Or my wife. Or my parents. Or my friends. Or my daughter’s nursery at home. Indeed, I have no real idea what the verb “to picture” is supposed to mean.

When my daughter was born last year, I was fifty-three years old. I’d wanted a child so badly for so long, and her arrival may well be the most wonderful thing ever to happen to me. And yet I cannot picture her first breath, though I witnessed it from inches away. I also cannot picture her right now, as I type these words. Or my wife. Or my parents. Or my friends. Or my daughter’s nursery at home. Indeed, I have no real idea what the verb “to picture” is supposed to mean.

How, after all, could I possibly picture what is not in front of me?

I say: After all. That is because I have aphantasia. I lack a mind’s eye. If you ask me to describe someone I cannot see at that moment, or something, I have no idea how to do it since my mind forms no pictures. The idea that a mind could form pictures is, to me, science fiction.

More here.

How AI is going to transform civilization over the next 5-10 years

Scott Aaronson at Shtetl-Optimized:

My friend Leopold Aschenbrenner, who I got to know and respect on OpenAI’s now-disbanded Superalignment team before he left the company under disputed circumstances, just released “Situational Awareness,” one of the most extraordinary documents I’ve ever read. With unusual clarity, concreteness, and seriousness, and with a noticeably different style than the LessWrongers with whom he shares some key beliefs, Leopold sets out his vision of how AI is going to transform civilization over the next 5-10 years. He makes a case that, even after ChatGPT and all that followed it, the world still hasn’t come close to “pricing in” what’s about to hit it. We’re still treating this as a business and technology story like personal computing or the Internet, rather than (also) a national security story like the birth of nuclear weapons, except more so. And we’re still indexing on LLMs’ current capabilities (“fine, so they can pass physics exams, but they still can’t do original physics research“), rather than looking at the difference between now and five years ago, and then trying our best to project forward an additional five years.

More here.

Israel’s Descent

Adam Shatz at the London Review of Books:

When Ariel Sharon withdrew more than eight thousand Jewish settlers from the Gaza Strip in 2005, his principal aim was to consolidate Israel’s colonisation of the West Bank, where the settler population immediately began to increase. But ‘disengagement’ had another purpose: to enable Israel’s air force to bomb Gaza at will, something they could not do when Israeli settlers lived there. The Palestinians of the West Bank have been, it seems, gruesomely lucky. They are encircled by settlers determined to steal their lands – and not at all hesitant about inflicting violence in the process – but the Jewish presence in their territory has spared them the mass bombardment and devastation to which Israel subjects the people of Gaza every few years.

The Israeli government refers to these episodes of collective punishment as ‘mowing the lawn’. In the last fifteen years, it has launched five offensives in the Strip.

More here.

Stuart Russell, “AI: What If We Succeed?”

From Géricault’s Monomanes To Balzac’s La Recherche De L’absolu

Michael Fried at nonsite:

Put slightly differently, my point in appending a reading of “Le Colonel Chabert” to my account of Géricault was to suggest that what we find in the painter’s career is ultimately the defeat of drama and expression in the Diderotian/Davidian sense of both, which is also to say, in the terms developed in my essay, at least a partial loss of world as representable by painting. Nor does French painting following Géricault’s death undo that defeat and that loss. As I remark in “Géricault’s Romanticism,” the two major figures that dominate the scene in the second half of the 1820s and 1830s, Ingres and Delacroix, found ways of bypassing or disabling the issue of theatricality by shifting the imaginative center of their art altogether elsewhere, toward what I think of as a “stylistic” or, better, “esthetic” register (GR, 58–60). By so doing both artists secured long and productive careers, ones, however, that from my point of view remained somewhat askew to the dominant thrust or dialectic of the central current of French nineteenth-century painting.

Put slightly differently, my point in appending a reading of “Le Colonel Chabert” to my account of Géricault was to suggest that what we find in the painter’s career is ultimately the defeat of drama and expression in the Diderotian/Davidian sense of both, which is also to say, in the terms developed in my essay, at least a partial loss of world as representable by painting. Nor does French painting following Géricault’s death undo that defeat and that loss. As I remark in “Géricault’s Romanticism,” the two major figures that dominate the scene in the second half of the 1820s and 1830s, Ingres and Delacroix, found ways of bypassing or disabling the issue of theatricality by shifting the imaginative center of their art altogether elsewhere, toward what I think of as a “stylistic” or, better, “esthetic” register (GR, 58–60). By so doing both artists secured long and productive careers, ones, however, that from my point of view remained somewhat askew to the dominant thrust or dialectic of the central current of French nineteenth-century painting.

more here.

Saurabh Netravalkar finds it hard to log off Slack. But a few weeks ago, the Oracle software engineer shipped his final code and set an out-of-office note on the messaging app to focus on a more personal goal: playing for the United States’ underdog cricket team at the T20 World Cup. “If there is anything urgent, my manager should be able to reach me,” he said in an interview with The Washington Post. “But I’m completely focused on the World Cup.”

Saurabh Netravalkar finds it hard to log off Slack. But a few weeks ago, the Oracle software engineer shipped his final code and set an out-of-office note on the messaging app to focus on a more personal goal: playing for the United States’ underdog cricket team at the T20 World Cup. “If there is anything urgent, my manager should be able to reach me,” he said in an interview with The Washington Post. “But I’m completely focused on the World Cup.”