Category: Recommended Reading

The Beguiling Crónicas of Hebe Uhart

Colm McKenna at The Millions:

Despite its growing popularity among Anglophone readers, the crónica—a unique form of literary reportage that blurs the lines of fact and fiction—remains a quintessentially Latin American genre. In English, scant studies on the form exist beyond 2002’s The Contemporary Mexican Chronicle. The genre has long been marked by its political, polemical overtones (Rodolfo Walsh’s Operation Massacre, for example), but increasing democratization across Latin American has seen it shift toward a lighter, more observational approach, in which the writer keeps their distance (as in Fernanda Melchor’s This Is Not Miami.)

Despite its growing popularity among Anglophone readers, the crónica—a unique form of literary reportage that blurs the lines of fact and fiction—remains a quintessentially Latin American genre. In English, scant studies on the form exist beyond 2002’s The Contemporary Mexican Chronicle. The genre has long been marked by its political, polemical overtones (Rodolfo Walsh’s Operation Massacre, for example), but increasing democratization across Latin American has seen it shift toward a lighter, more observational approach, in which the writer keeps their distance (as in Fernanda Melchor’s This Is Not Miami.)

Toward the end of her life, the late Argentine writer Hebe Uhart—known for her novels, short stories, and travel logs—almost exclusively wrote crónicas. She turned to the form because “she felt that what the world had to offer was more interesting than her own experience or imagination,” writes Mariana Enriquez in the introduction to A Question of Belonging, a collection 25 of Uhart’s crónicas that probe her daily life and travels across Latin America.

more here.

Lucas Rijneveld’s Novel Takes Nabokov To The Farm

Katie Kadue at Bookforum:

LO. LEE. TA. This is the trip the tip of the tongue expects to take when reading a novel from the point of view of a man currently incarcerated following the rape of a teenage girl he’s groomed. And at the tender age of thirteen pages into Lucas Rijneveld’s My Heavenly Favorite, an attentive reader may indeed murmur “Lolita!” when the unnamed narrator, a former farm veterinarian from the Dutch countryside, refers to the titular “favorite,” also unnamed, as “the fire of my loins.” So far, so Lo.

LO. LEE. TA. This is the trip the tip of the tongue expects to take when reading a novel from the point of view of a man currently incarcerated following the rape of a teenage girl he’s groomed. And at the tender age of thirteen pages into Lucas Rijneveld’s My Heavenly Favorite, an attentive reader may indeed murmur “Lolita!” when the unnamed narrator, a former farm veterinarian from the Dutch countryside, refers to the titular “favorite,” also unnamed, as “the fire of my loins.” So far, so Lo.

Initial press for the novel, originally written in Dutch and translated by Michele Hutchison, has fed the frenzy of Lolitapalooza. It’s been called “a modern Lolita,” “a novel that wears its debt to Lolita . . . pinned on its chest with abject pride,” “a queer and profane take on the Lolita archetype,” “Lolita-esque,” “a cowshit-splashed Lolita.” Someone who picks up a copy and skims the blurbs might wonder if we really need another male-authored Lolita from the first-person perspective of the pedophile, no matter how spruced up with shit, no matter how daringly different.

more here.

Can you pass a U.S. citizenship test? Take our civics quiz

Emma Uber in The Washington Post:

While the Fourth of July conjures up images of fireworks and parades, barbecues and bonfires, the United States has another Independence Day tradition: naturalizing new citizens. An estimated 11,000 people will celebrate the holiday this year by officially becoming American citizens, double the number from 2023. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services organized 195 naturalization ceremonies around the globe between June 28 and July 5 in honor of Independence Day. A handful of the ceremonies will take place at historical landmarks, meaning some will swear their oath of allegiance at George Washington’s Mount Vernon or Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello on July 4.

While the Fourth of July conjures up images of fireworks and parades, barbecues and bonfires, the United States has another Independence Day tradition: naturalizing new citizens. An estimated 11,000 people will celebrate the holiday this year by officially becoming American citizens, double the number from 2023. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services organized 195 naturalization ceremonies around the globe between June 28 and July 5 in honor of Independence Day. A handful of the ceremonies will take place at historical landmarks, meaning some will swear their oath of allegiance at George Washington’s Mount Vernon or Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello on July 4.

Before partaking in the ceremonies, all aspiring U.S. citizens must pass a two-part test. The first part requires test takers to demonstrate an understanding of English. The second part is an oral exam of 10 civics questions chosen from a list of 100. The Washington Post set up 10 multiple choice questions based on the list of 100 questions USCIS provides as study material to help readers gauge how they would perform. Test takers must answer six questions correctly to pass. Can you?

More here.

Thursday Poem

Selecting a Reader

First, I would have her be beautiful,

and walking carefully up on my poetry

at the loneliest moment of the afternoon,

her hair still damp at the neck

from washing it. She should be wearing

a raincoat, an old one, dirty

from not having money enough for the cleaners.

She will take out her glasses, and there

in the bookstore, she will thumb

over my poems, then put the book back

up on its shelf. She will say to herself,

“For that kind of money, I can get

my raincoat cleaned.” And she will.

Ted Kooser

from Poetry 180

Radom House, 2003

Mind-reading AI recreates what you’re looking at with amazing accuracy

Michael Le Page in New Scientist:

Artificial intelligence systems can now create remarkably accurate reconstructions of what someone is looking at based on recordings of their brain activity. These reconstructed images are greatly improved when the AI learns which parts of the brain to pay attention to. “As far as I know, these are the closest, most accurate reconstructions,” says Umut Güçlü at Radboud University in the Netherlands. Güçlü’s team is one of several around the world using AI systems to work out what animals or people are seeing from brain recordings and scans. In one previous study, his team used a functional MRI (fMRI) scanner to record the brain activity of three people as they were shown a series of photographs.

Artificial intelligence systems can now create remarkably accurate reconstructions of what someone is looking at based on recordings of their brain activity. These reconstructed images are greatly improved when the AI learns which parts of the brain to pay attention to. “As far as I know, these are the closest, most accurate reconstructions,” says Umut Güçlü at Radboud University in the Netherlands. Güçlü’s team is one of several around the world using AI systems to work out what animals or people are seeing from brain recordings and scans. In one previous study, his team used a functional MRI (fMRI) scanner to record the brain activity of three people as they were shown a series of photographs.

In another study, the team used implanted electrode arrays to directly record the brain activity of a single macaque monkey as it looked at AI-generated images. This implant was done for other purposes by another team, says Güçlü’s colleague Thirza Dado, also at Radboud University. “The macaque was not implanted so that we can do reconstruction of perception,” she says. “That is not a good argument to do surgery on animals.” The team has now reanalysed the data from these previous studies using an improved AI system that can learn which parts of the brain it should pay most attention to.

More here.

Wednesday, July 3, 2024

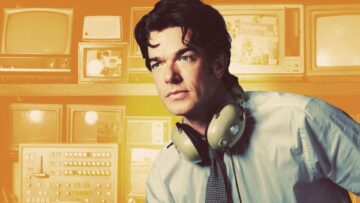

On John Mulaney’s “Everybody’s in L.A.”

Henry Luzzatto in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

DESPITE ITS HOST’S supremely confident stage persona, John Mulaney Presents: Everybody’s in L.A. starts out self-conscious. In his opening monologue, Mulaney explains that he doesn’t really understand the point of the show and assures the audience that, with only six episodes streamed live and nightly on Netflix, it “will never hit its groove.” He’s right to worry. With everything from traditional call-in segments and monologues to chaotic guest cross talk to a robot-based running gag and semi-real, semi-staged portraits of Los Angeles, the show is a chaotic mix of disparate comedic modes that constantly dares itself not to work.

DESPITE ITS HOST’S supremely confident stage persona, John Mulaney Presents: Everybody’s in L.A. starts out self-conscious. In his opening monologue, Mulaney explains that he doesn’t really understand the point of the show and assures the audience that, with only six episodes streamed live and nightly on Netflix, it “will never hit its groove.” He’s right to worry. With everything from traditional call-in segments and monologues to chaotic guest cross talk to a robot-based running gag and semi-real, semi-staged portraits of Los Angeles, the show is a chaotic mix of disparate comedic modes that constantly dares itself not to work.

But while Mulaney lampshades the show’s oddball, seat-of-its pants approach, this setup doesn’t stop Everybody’s in L.A. from hitting its stride. In fact, it may help, since the improbable combination of tones and ideas is what makes this show—maybe even more than its liveness—feel unique among Netflix’s new comedy lineup. Instead of rehashing the format of traditional late night, Mulaney uses its structural and tonal looseness to build something specific to his voice and the streaming medium.

More here.

When RAND Made Magic in Santa Monica

Pradyumna Prasad and Jordan Schneider in Asterisk:

Between 1945 and 1960, RAND operated as the world’s most productive research organization. Initially envisioned as a research arm of the Air Force, RAND made century-defining breakthroughs both in basic science and applied strategic analysis. Its members helped define U.S. nuclear strategy, conceptualized satellites, pioneered systems analysis, and developed the earliest reports on defense economics. They also revolutionized much of STEM: RAND scholars developed the basics of game theory, linear programming, and Monte Carlo methods. They helped conceptualize generalized artificial intelligence, developed the basics for packet switching (which enables data transmission across networks), and built one of the world’s first computers.

Between 1945 and 1960, RAND operated as the world’s most productive research organization. Initially envisioned as a research arm of the Air Force, RAND made century-defining breakthroughs both in basic science and applied strategic analysis. Its members helped define U.S. nuclear strategy, conceptualized satellites, pioneered systems analysis, and developed the earliest reports on defense economics. They also revolutionized much of STEM: RAND scholars developed the basics of game theory, linear programming, and Monte Carlo methods. They helped conceptualize generalized artificial intelligence, developed the basics for packet switching (which enables data transmission across networks), and built one of the world’s first computers.

Today, RAND remains a successful think tank — by some metrics, among the world’s best.1 In 2022, it brought in over $350 million in revenue, and large proportions still come from contracts with the US military. Its graduate school is among the largest for public policy in America.

But RAND’s modern achievements don’t capture the same fundamental policy mindshare as they once did.

More here.

University Presidents Discuss Open Inquiry & Institutional Neutrality

Julian Assange is finally free – but should not have been prosecuted in the first place

Ken Roth in The Guardian:

Julian Assange’s lengthy detention has finally ended, but the danger that his prosecution poses to the rights of journalists remains. As is widely known, the US government’s pursuit of Assange under the Espionage Act threatens to criminalize common journalistic practices. Sadly, Assange’s guilty plea and release from custody have done nothing to ease that threat.

Julian Assange’s lengthy detention has finally ended, but the danger that his prosecution poses to the rights of journalists remains. As is widely known, the US government’s pursuit of Assange under the Espionage Act threatens to criminalize common journalistic practices. Sadly, Assange’s guilty plea and release from custody have done nothing to ease that threat.

That Assange was indicted under the Espionage Act, a US law designed to punish spies and traitors, should not be considered the normal course of business. Barack Obama’s justice department never charged Assange because it couldn’t distinguish what he had done from ordinary journalism. The espionage charges were filed by the justice department of Donald Trump. Joe Biden could have reverted to the Obama position and withdrawn the charges but never did.

More here.

How Far Can We Scale AI?

Cupcakes and Crotch Kicks: On “What Makes Sammy Jr. Run?”

Tom Zoellner at the LARB:

Editor Alex Belth has created an unusual literary anthology of some of the best celebrity magazine profiles from 1959 to 1979, what is generally regarded—at least by publishing old-timers—as the peak years of the genre, before the ferret-faced publicists cracked down on honesty and budgets ran dry. What Makes Sammy Jr. Run? Classic Celebrity Journalism Volume 1 (1960s and 1970s), published by the Sager Group this spring, puts 18 long-form stories about well-known actors, writers, and musicians into one place. The result is like a walk through a delightful museum of postwar America, with all its bright spots and faults.

Editor Alex Belth has created an unusual literary anthology of some of the best celebrity magazine profiles from 1959 to 1979, what is generally regarded—at least by publishing old-timers—as the peak years of the genre, before the ferret-faced publicists cracked down on honesty and budgets ran dry. What Makes Sammy Jr. Run? Classic Celebrity Journalism Volume 1 (1960s and 1970s), published by the Sager Group this spring, puts 18 long-form stories about well-known actors, writers, and musicians into one place. The result is like a walk through a delightful museum of postwar America, with all its bright spots and faults.

The nostalgia for a lost era runs even thicker. Not only have celebrity profiles gotten flatter and duller—the canned hotel room conversation hardly makes for fun reading—but the entire medium of magazines has also taken serious economic blows and thinned out. Celebrities now do more direct and manageable communications with their fans through social media. Who needs to invite the annoying writer, that jealous guttersnipe hiding a knife in their back pocket?

more here.

America has a big birthday coming. How could we possibly celebrate it?

Jesus Rodriguez in The Washington Post:

In the course of human events, America has come to agree on one thing: that any modern birthday celebration of itself will involve sizzling hunks of meat, Springsteen in the ears, smoke in the eyes, sulfur in the nostrils, rockets’ red glare.

In the course of human events, America has come to agree on one thing: that any modern birthday celebration of itself will involve sizzling hunks of meat, Springsteen in the ears, smoke in the eyes, sulfur in the nostrils, rockets’ red glare.

What’s less self-evident is how to appropriately mark a big birthday — like America’s 250th, two short years away — at a time when the country is so politically split that many Americans may be ready to declare the Great Experiment kaput after November. A survey this year by Gallup found that 67 percent of adults feel either “very proud” or “extremely proud” to be American — down from 85 percent in 2013 and 90 percent in 2003. A much lower percentage say they are satisfied with the way things are going: 21 percent, in June. Two-thirds of the people who responded to a January Quinnipiac poll said they believed American democracy was in danger of collapsing. Historians have been sounding alarm bells, and this week Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor and two of her colleagues, dissenting against the court’s ruling that presidents have absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts, said the court’s conservative majority had just made the president into “a king above the law,” upending “the status quo that has existed since the Founding.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Morning in the Burned House

In the burned house I am eating breakfast.

You understand: there is no house, there is no breakfast,

yet here I am.

The spoon which was melted scrapes against

the bowl which was melted also.

No one else is around.

Where have they gone to, brother and sister,

mother and father? Off along the shore,

perhaps. Their clothes are still on the hangers,

their dishes piled beside the sink,

which is beside the woodstove

with its grate and sooty kettle,

every detail clear,

tin cup and rippled mirror.

The day is bright and songless,

the lake is blue, the forest watchful.

In the east a bank of cloud

rises up silently like dark bread.

I can see the swirls in the oilcloth,

I can see the flaws in the glass,

those flares where the sun hits them.

I can’t see my own arms and legs

or know if this is a trap or blessing,

finding myself back here, where everything

in this house has long been over,

kettle and mirror, spoon and bowl,

including my own body,

including the body I had then,

including the body I have now

as I sit at this morning table, alone and happy,

bare child’s feet on the scorched floorboards

(I can almost see)

in my burning clothes, the thin green shorts

and grubby yellow T-shirt

holding my cindery, non-existent,

radiant flesh. Incandescent.

by Margaret Atwood

from Morning in the Burned House

Houghton Mifflin Co., 1995

mRNA Cancer Vaccines Spark Renewed Hope as Clinical Trials Gain Momentum

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

When Angela received her first shot at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in early 2020, Covid-19 was months away. Far from a household name, mRNA vaccines were mostly relegated to lab studies. Yet the jab she received was made of the same technology. A melanoma patient, Angela had multiple malignant moles removed. Alongside an established immune-stimulating drug, the hope was the duo could fight off any residual cancerous cells and slash the chances of relapse. Scientists have long sought cancer vaccines that prevent the pesky cells from growing back. Like those targeting viruses, the vaccines would train the body’s immune system to recognize the cancerous cells and attack and eliminate them before they could grow and spread. Despite decades of research into cancer vaccines, the dream has mostly failed. One reason is that every cancer, in every person, is different. So is each person’s immune system. Tailoring vaccines to neutralize cancers for each patient would not only be expensive, but sometimes impossible due to how long they’d take to develop—time is not on cancer patients’ sides.

When Angela received her first shot at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in early 2020, Covid-19 was months away. Far from a household name, mRNA vaccines were mostly relegated to lab studies. Yet the jab she received was made of the same technology. A melanoma patient, Angela had multiple malignant moles removed. Alongside an established immune-stimulating drug, the hope was the duo could fight off any residual cancerous cells and slash the chances of relapse. Scientists have long sought cancer vaccines that prevent the pesky cells from growing back. Like those targeting viruses, the vaccines would train the body’s immune system to recognize the cancerous cells and attack and eliminate them before they could grow and spread. Despite decades of research into cancer vaccines, the dream has mostly failed. One reason is that every cancer, in every person, is different. So is each person’s immune system. Tailoring vaccines to neutralize cancers for each patient would not only be expensive, but sometimes impossible due to how long they’d take to develop—time is not on cancer patients’ sides.

In contrast, mRNA vaccines are far speedier to build. After they were removed, Angela’s malignant moles were analyzed for specific cancerous “fingerprints” or neoantigens. Based on these proteins, scientists at Moderna—known for their Covid-19 vaccines—built a custom mRNA cancer vaccine to train her immune system to prevent her own cancer from recurring.

More here.

The Fantastical Lives of Ikbal and Idries Shah

Fitzroy Morrissey at Literary Review:

Shortly before his death in 1974, R C Zaehner, Spalding Professor of Eastern Religions and Ethics at Oxford, observed that young Westerners who had turned away from Christianity were more often drawn to the religions of India and the Far East than to Islam. ‘The young’, the devoutly Catholic Zaehner stated, ‘are not interested in switching from one dogmatic monotheistic faith to another: hence they are little interested in Islam except when Islam itself is turned upside down and becomes Sufism, which in its developed form is barely distinguishable from Vedanta.’ ‘Indeed,’ he went on, ‘that egregious populariser Idries Shah has gone so far as to claim Zen as a manifestation of Sufism.’ This, Zaehner declared, was historical ‘nonsense’ and academically ‘detestable’.

Shortly before his death in 1974, R C Zaehner, Spalding Professor of Eastern Religions and Ethics at Oxford, observed that young Westerners who had turned away from Christianity were more often drawn to the religions of India and the Far East than to Islam. ‘The young’, the devoutly Catholic Zaehner stated, ‘are not interested in switching from one dogmatic monotheistic faith to another: hence they are little interested in Islam except when Islam itself is turned upside down and becomes Sufism, which in its developed form is barely distinguishable from Vedanta.’ ‘Indeed,’ he went on, ‘that egregious populariser Idries Shah has gone so far as to claim Zen as a manifestation of Sufism.’ This, Zaehner declared, was historical ‘nonsense’ and academically ‘detestable’.

Zaehner was referring to Shah’s The Sufis, which, since its publication in 1964, had become the most widely read book on Sufism in English. Helped by an introduction by the poet Robert Graves, The Sufis had met with critical acclaim. Writing in The Listener, the weekly magazine of the BBC, Ted Hughes described the book as ‘astonishing’, while, in The Spectator, Doris Lessing wrote that she couldn’t remember being more provoked or stimulated.

more here.

Tuesday, July 2, 2024

Ismail Kadare, giant of Albanian literature, dies aged 88

Richard Lea in The Guardian:

Writing under the shadow of Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha, Kadare examined contemporary society through the lens of allegory and myth in novels including The General of the Dead Army, The Siege and The Palace of Dreams. After fleeing to Paris just months before Albania’s communist government collapsed in 1990, his reputation continued to grow as he kept returning to the region in his fiction. Translated into more than 40 languages, he won a series of awards including the Man Booker International prize.

Writing under the shadow of Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha, Kadare examined contemporary society through the lens of allegory and myth in novels including The General of the Dead Army, The Siege and The Palace of Dreams. After fleeing to Paris just months before Albania’s communist government collapsed in 1990, his reputation continued to grow as he kept returning to the region in his fiction. Translated into more than 40 languages, he won a series of awards including the Man Booker International prize.

Born in 1936 in Gjirokastër, an Ottoman fortress city not far from the Greek border, Kadare grew up on the street where Hoxha had lived a generation before. He published his first collection of poetry aged 17.

More here.

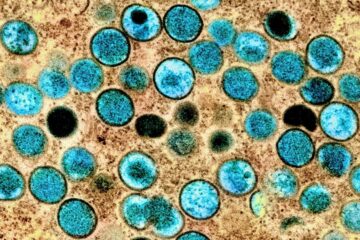

Dangerous mpox strain spreading in Democratic Republic of the Congo

Michael Le Page in New Scientist:

Urgent action is needed to try to contain the spread of a new strain of mpox transmitted mainly by heterosexual sex that has caused more than 1000 cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, say health experts dealing with the outbreak. They fear the condition is poised to spread to neighbouring countries and possibly further afield.

Urgent action is needed to try to contain the spread of a new strain of mpox transmitted mainly by heterosexual sex that has caused more than 1000 cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, say health experts dealing with the outbreak. They fear the condition is poised to spread to neighbouring countries and possibly further afield.

“It’s undoubtedly the most dangerous so far of all the known strains of mpox considering how it is transmitted, how it is spread and also the symptoms,” says John Claude Udahemuka at the University of Rwanda.

The new strain was first identified in the small mining town of Kamituga in South Kivu province in the east of the DRC in September. In recent weeks it has spread to cities in the area. It may already have reached neighbouring countries such as Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda, says Leandre Murhula Masirika at the South Kivu health department.

More here.

Linguist John McWhorter interviewed by Richard Dawkins

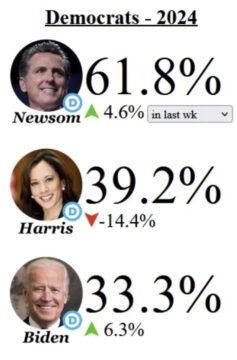

Prediction Markets Suggest Replacing Biden

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

Some of the party’s problems are hard and have no shortcuts. But the big one – figuring out whether replacing Biden would even help the Democrats’ electoral chances – is a good match for prediction markets. Set up markets to find the probability of Democrats winning they nominate Biden, vs. the probability of Democrats winning if they replace him with someone else.

Some of the party’s problems are hard and have no shortcuts. But the big one – figuring out whether replacing Biden would even help the Democrats’ electoral chances – is a good match for prediction markets. Set up markets to find the probability of Democrats winning they nominate Biden, vs. the probability of Democrats winning if they replace him with someone else.

(see my Prediction Market FAQ for why I think they are good for cases like these)

Before we go into specifics, the summary result: Replacing Biden with Harris is neutral to slightly positive; replacing Biden with Newsom or a generic Democrat increases their odds of winning by 10 – 15 percentage points. There are some potential technical objections to this claim, but they mostly suggest reasons why the markets might overestimate Biden’s chances rather than underestimate them.