Category: Recommended Reading

Anouk Aimée (1932 – 2024) Actor

Saturday, June 29, 2024

Moving Beyond the “Democracy vs. Far Right” Division

Cas Mudde in The Ideas Letter:

2024 is the Super Election Year: most of the world’s population is eligible to vote in (more or less) democratic elections. From India to the US, many of these elections are framed as an existential fight between “democracy” and “the far right”. It is striking how stale this framing has become. For at least a decade now, many elections have been cast as a contest between an embattled center and an emboldened far right – despite the media shying away from using “normative” terms, like “far right” or “racism”, so as to not provoke the now largely normalized far right and its increasingly influential supporters.

The European elections of 6-9 June, a collection of 27 national elections for the same legislative institution, the European Parliament, were framed in these terms. Just as in 2014 and 2019, alarmist accounts predicted massive gains for the far right and some even asked whether this could be the end of Europe, conflating an ill-defined continent (Europe) with a specific political institution (the European Union). In the end, the international media decided on two conclusions: “the center holds” and “the far right surges” – brought together in the dramatic New York Times headline: “In the E.U. Elections, the Center Holds, but the Far Right Still Wreaks Havoc”. While not completely wrong, it obscures more than it highlights.

The problem with this framing is that it assumes a fundamental opposition between “the center” and “the far right” that is no longer true (if it ever was). The term “the center” is extremely vague and, to some extent, meaningless because it is a positional term which shifts whenever the left and/or right poles move.

More here.

The Gay Men Who Built the Conservative Movement

Transforming Mexico

Edwin F. Ackerman in Sidecar:

Claudia Sheinbaum won a landslide in the Mexican presidential elections on 2 June. With close to 60% of the vote, the magnitude of her victory exceeded that of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2018. Her party, Morena, formed only a decade ago, secured a two-thirds majority in Congress and is just two representatives short of doing so in the Senate. The opposition PRI, PAN and PRD – running on a unity ticket – got about 27%, a significant decline since the previous ballot. Three things are particularly striking about the results. First, the clarity of the mandate: an anomaly in Western democracies, which are increasingly accustomed to marginal contests and political stalemates. Second, the particularities of Morena’s constituency: a voting bloc anchored in the working classes yet capable of folding in parts of the middle strata. Third, the sense that a new political regime is emerging, founded on a post-neoliberal social pact.

Sheinbaum’s main competitor was Xóchitl Gálvez, leading the coalition of the PRI, PAN and PRD. Gálvez helmed an erratic campaign, representing the interests of big business sprinkled with lite social liberalism. Unable to run on an outwardly neoliberal agenda – the term has become toxic in Mexico – she opted instead for identity politics: her opening pitch emphasized her indigenous roots and humble beginnings, while her closing one leaned in to attacks on Sheinbaum’s non-Catholicism.

More here.

Agreeing to Our Harm

Marilynne Robinson in the NY Review of Books:

Some years ago I spoke at a conservative church in northern Michigan. I talked about military-style guns and the culture of fear and resentment that rationalized the zeal for them. My point was that they and the passions associated with them should have no place among people who claim to be Christians. When I finished there was silence. Then a woman raised her hand and asked why no one had been prosecuted for the Iraq War. It was not a question I expected, to say the least. I had no answer.

The woman was gracious, not at all confrontational. But clearly she had asked her question as a kind of rebuttal to what I had said about guns. When I had time to think about it, I decided she was asking me which was the graver danger—that weapons had seized upon the imagination of an important subset of the population, together with threats and fantasies of using them against people and institutions within their own country, or that a president could throw the American armed forces unprepared into a war, with heavy losses on both sides, and that he could do this on the basis of thin or doubtful information, if not simply from a sense of private grievance and a privileged indifference to other considerations. Now the Supreme Court is mulling the possibility of making real in law the presidential immunity from prosecution, the privileging of power that had, as fact, offended the woman’s sense of justice and safety.

To weigh one grievous threat against another is not a very useful exercise. There is no point in seeming to minimize either one.

More here.

Kende Ne Naina – Noor Jehan

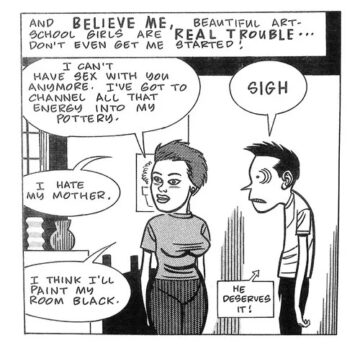

Culture, Digested: The PhD in Creativity

Jessa Crispin in The Culture We Deserve:

One of the more interesting asides in the extensive coverage of Philadelphia’s University of the Arts’ shutdown has been the information that in the past few years the institution had been offering a PhD in creativity. The first handful of recipients were awarded their degrees in 2022 – among them were a “psychotherapist, a wine writer, an Ethiopian filmmaker, and a Philadelphia School District administrator.” Unlike a traditional PhD program, where a small number of candidates are selected to contribute to a field’s base of knowledge with original research and scholarship, this doctorate was sponsored by a whiskey distillery and sought to teach students “to think more creatively” through “intensive immersion in creative thinking,” according to the university’s official website. (It also deviates from many other PhD programs by charging tuition – more than $50,000 a year for at least three years – and fees, rather than being one of the fully funded programs that is the university norm.)

One of the more interesting asides in the extensive coverage of Philadelphia’s University of the Arts’ shutdown has been the information that in the past few years the institution had been offering a PhD in creativity. The first handful of recipients were awarded their degrees in 2022 – among them were a “psychotherapist, a wine writer, an Ethiopian filmmaker, and a Philadelphia School District administrator.” Unlike a traditional PhD program, where a small number of candidates are selected to contribute to a field’s base of knowledge with original research and scholarship, this doctorate was sponsored by a whiskey distillery and sought to teach students “to think more creatively” through “intensive immersion in creative thinking,” according to the university’s official website. (It also deviates from many other PhD programs by charging tuition – more than $50,000 a year for at least three years – and fees, rather than being one of the fully funded programs that is the university norm.)

…How can anyone fail a PhD program in creativity, when creativity is a word that can mean absolutely anything? It is a perfect encapsulation of what the contemporary arts institution has turned into: a university more focused on money than pedagogy, the transformation of the ivory tower into a corporate boardroom, and the focus on churning out creatives than artists.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Border

I’m going to move ahead.

Behind me my whole family is calling,

My child is pulling my sari-end,

My husband stands blocking the door,

But I will go.

There’s nothing ahead but a river.

I will cross.

I know how to swim,

but they won’t let me swim, won’t let me cross.

There’s nothing on the other side of the river

but a vast expanse of fields,

But I’ll touch this emptiness once

and run against the wind, whose whooshing sound

makes me want to dance.

I’ll dance someday

and then return.

I’ve not played keep-away for years

as I did in childhood.

I’ll raise a great commotion playing keep-away someday

and then return.

For years I haven’t cried with my head

in the lap of solitude.

I’ll cry to my heart’s content someday

and then return.

There’s nothing ahead but a river,

and I know how to swim.

Why shouldn’t I go?

I’ll go.

by Taslima Nasrin

and here

Friday, June 28, 2024

Privilege, Blackmail, and Murder for Hire in Austin

Katy Vine and Ana Worrel in Texas Monthly:

Erik Maund had always lived the high life, as you might expect of a man whose surname had been blasted on TV ads for decades. By the time he was in his forties, he was an executive at Maund Automotive Group, a car sales business whose first dealership was opened by his grandfather Charles Maund. “If you say the Maund name in Austin in a 7-Eleven, two people say, ‘I bought a car from him,’ ” said Wallace Lundgren, a retired Chevrolet dealer. Austinites could probably recognize the major names in the car business better than they could identify any local politician. And members of the city’s old power circles would recognize Erik—a six-foot-three white guy with short brown hair, a boxy head, and heavy-lidded eyes tucked under a straight brow—as a likely heir to the business.

Erik Maund had always lived the high life, as you might expect of a man whose surname had been blasted on TV ads for decades. By the time he was in his forties, he was an executive at Maund Automotive Group, a car sales business whose first dealership was opened by his grandfather Charles Maund. “If you say the Maund name in Austin in a 7-Eleven, two people say, ‘I bought a car from him,’ ” said Wallace Lundgren, a retired Chevrolet dealer. Austinites could probably recognize the major names in the car business better than they could identify any local politician. And members of the city’s old power circles would recognize Erik—a six-foot-three white guy with short brown hair, a boxy head, and heavy-lidded eyes tucked under a straight brow—as a likely heir to the business.

He and his wife, Sheri, a former dealership office worker, had raised two kids to the cusp of adulthood and lived in a seven-thousand-square-foot white brick mansion next to the Austin Country Club, where he teed off regularly with a close-knit group of friends. He owned a boat and a lake house. On Sundays he often enjoyed brunch at the club with his family.

But on March 1, 2020, as the world was rattled by reports of a highly contagious virus turning up in nation after nation, Erik received a text that demanded his attention. It came from a stranger who knew about a night Erik had spent with an escort in Nashville a few weeks earlier and wanted money to keep quiet.

More here.

AI: Hope or Hype?

From Project Syndicate:

The technology certainly has the potential to improve family life, suggest New America’s Anne-Marie Slaughter and Milo’s Avni Patel Thompson. By taking over “repetitive and mundane tasks,” it would “enable human caregivers to spend more time establishing emotional connections and providing companionship.” Though developing an “AI for caregivers” would “test the technology’s technical limits and determine the extent to which it can account for moral considerations and societal values,” it would undoubtedly be “worth the effort.”

The technology certainly has the potential to improve family life, suggest New America’s Anne-Marie Slaughter and Milo’s Avni Patel Thompson. By taking over “repetitive and mundane tasks,” it would “enable human caregivers to spend more time establishing emotional connections and providing companionship.” Though developing an “AI for caregivers” would “test the technology’s technical limits and determine the extent to which it can account for moral considerations and societal values,” it would undoubtedly be “worth the effort.”

Jamie Metzl of OneShared.World offers an even more sweeping vision of AI’s potential, arguing that the technology could help people incorporate into their “traditional identities” a “global consciousness and a greater awareness of how to meet the collective needs of society.” To this end, we should prompt AI systems to “help us imagine a better path forward,” including a “global framework for addressing” common challenges.

More here.

How America Got Into This Omnishambles

Yascha Mounk at Persuasion:

America is in deep, deep trouble.

America is in deep, deep trouble.

Before Thursday’s debate, the leading contender to win the upcoming presidential election was already Donald Trump, a man whose first stint in the White House provided all the necessary evidence that he is spectacularly ill-suited for the job. During that term in office, Trump ruled rashly and selfishly. He lavished praise on his appointees before firing scores of them for incompetence or insubordination. He picked constant fights with the independent institutions that preserve the separation of powers. And when he lost a hard-fought race, he refused to concede defeat, inspiring a mob to assault Congress, and breaking the key norm that has sustained the American Republic for the past centuries.

After Thursday’s debate, it has become painfully obvious that the only man who stands between Trump and the White House is no longer mentally fit for the job.

More here.

Jon Stewart’s Debate Analysis: Trump’s Blatant Lies and Biden’s Senior Moments

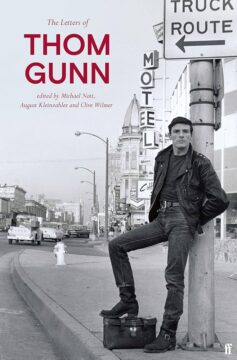

The Antimonies Of Thom Gunn

Anthony Domestico at The Baffler:

THOM GUNN WAS THE GREAT RHAPSODE OF RISK. In a 1961 love letter to queer San Francisco, the poem’s speaker looks from afar at the drunken revelers and hungry cruisers in the darkened streets below: “By the recurrent lights I see / Endless potentiality, / The crowded, broken, and unfinished! / I would not have the risk diminished.” In other poems, Gunn “adore[s] / The risk that made robust, / A world of wonders in / Each challenge to the skin,” admires “the pull and risk / Of the Pacific’s touch,” and lauds those who “properly / test[ed] themselves against risk, / as a human must, and does.” Risk was as essential to Gunn’s writing as it was to his living. “You get so absorbed in the experience of writing the poem,” he observed in a 1996 letter, “and take the occasional risk you hope is worth it—no, that’s wrong, you take constant risks, every line is a risk.” To write poetry is to know that you might fail and take the gamble anyway.

THOM GUNN WAS THE GREAT RHAPSODE OF RISK. In a 1961 love letter to queer San Francisco, the poem’s speaker looks from afar at the drunken revelers and hungry cruisers in the darkened streets below: “By the recurrent lights I see / Endless potentiality, / The crowded, broken, and unfinished! / I would not have the risk diminished.” In other poems, Gunn “adore[s] / The risk that made robust, / A world of wonders in / Each challenge to the skin,” admires “the pull and risk / Of the Pacific’s touch,” and lauds those who “properly / test[ed] themselves against risk, / as a human must, and does.” Risk was as essential to Gunn’s writing as it was to his living. “You get so absorbed in the experience of writing the poem,” he observed in a 1996 letter, “and take the occasional risk you hope is worth it—no, that’s wrong, you take constant risks, every line is a risk.” To write poetry is to know that you might fail and take the gamble anyway.

And yet, even while he loved the vertiginous experience of risk, Gunn loved the equanimity of balance equally. Though he wrote about hot things—sex, drugs, ecstasy of all kinds—his style was one of controlled coolness.

more here.

Thom Gunn Reads “Her Pet”

Was the Debate the Beginning of the End of Joe Biden’s Presidency?

Susan Glasser in The New Yorker:

It didn’t take long. From the very start of Thursday’s CNN debate between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, the question was not so much whether Biden was losing but exactly how much damage it would do to the President’s reëlection campaign. His first shaky answers, it turned out, were no outlier: Biden, his voice raspy and often unclear, struggled for the entirety of the debate, an agonizing hour and a half that, amazingly enough, Biden’s own campaign had sought out in an effort to make up ground against Trump, the defeated, criminally convicted ex-President who was nonetheless leading in the polls.

It didn’t take long. From the very start of Thursday’s CNN debate between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, the question was not so much whether Biden was losing but exactly how much damage it would do to the President’s reëlection campaign. His first shaky answers, it turned out, were no outlier: Biden, his voice raspy and often unclear, struggled for the entirety of the debate, an agonizing hour and a half that, amazingly enough, Biden’s own campaign had sought out in an effort to make up ground against Trump, the defeated, criminally convicted ex-President who was nonetheless leading in the polls.

Let’s stipulate to this: Trump was no champion, either. For much of the debate, he reiterated familiar lines, often out of context or wildly untrue, from his rallies and social-media feed. CNN’s moderators, having announced in advance that they would not be doing any fact checking, stuck to their plan, and the Trumpian B.S. flowed freely: The Greatest Economy Ever! Biden’s Is the Worst Administration Ever! Russia, Russia, Russia! Some of Trump’s lies were flagrant and damaging; others were merely bizarre. But did anyone care? The news of the debate was not Trump saying crazy, untrue things, though he did so in abundance. It was Biden. The President of the United States, eighty-one years old and asking to be returned to office until age eighty-six, looked and sounded old. Too old.

More here.

Biden Must Drop Out. Here’s How Democrats Could Replace Him on the Ticket

David Faris in Slate:

Thursday night’s debate was, and I don’t say this lightly, a disaster without any conceivable parallel in modern American political history for President Joe Biden, the Democratic Party, and anyone who cares about the future of our flawed but vital democracy. The president’s performance on CNN was nightmarishly confused and worrisome.

Thursday night’s debate was, and I don’t say this lightly, a disaster without any conceivable parallel in modern American political history for President Joe Biden, the Democratic Party, and anyone who cares about the future of our flawed but vital democracy. The president’s performance on CNN was nightmarishly confused and worrisome.

…There are essentially three paths to a new Democratic nominee, and all are completely unprecedented. For all of American history, even when modern medicine was still a twinkle in everyone’s eye, neither party has had to replace a presumptive nominee this close to the election. It might seem crazy, but one path is: Biden could simply resign. And in many ways, this is the easiest and simplest route to a new nominee. When he got back to the White House after the debate, he must have seen or been briefed on the cable news roundtables, the Twitter chatter, and the general atmosphere of total panic that his cataclysmic performance caused in Democratic circles all over the country. Even if, up to that very moment, he truly believed that he was the only person in the country who could beat Donald Trump, he surely cannot believe it any longer unless he has descended into a state of unreachable delusion.

If Biden were to resign, making Vice President Kamala Harris the president, it would instantly resolve any looming debate about what would happen at the Chicago convention in August. A President Harris would have six weeks to build momentum, shore up the party’s coalition, and lean into the inherent gravitas of the presidency. Freed from the constraints of the vice presidency, she might just prove a lot of doubters wrong about her political skills. If Harris were even a teeny-tiny bit more popular, there wouldn’t be any question about anointing her whatsoever, and it is worth noting that her net disapproval is now lower than either Trump’s or Biden’s, according to FiveThirtyEight.

More here.

The Philosophy Of Erring

Sam Alma at Aeon Magazine:

You are standing on a boat that is drifting down a placid river. You watch the trees on the shore glide along. For a moment, it looks like the trees themselves are moving – not your boat. But this, of course, is mere appearance: the trees are still, and it is your boat that moves. This parallax effect was described by medieval philosophers, but it may be more familiar in another form: when you’re sitting on a train slowly rolling out of the station, it can seem like it is the stationary train next to yours that is departing instead.

You are standing on a boat that is drifting down a placid river. You watch the trees on the shore glide along. For a moment, it looks like the trees themselves are moving – not your boat. But this, of course, is mere appearance: the trees are still, and it is your boat that moves. This parallax effect was described by medieval philosophers, but it may be more familiar in another form: when you’re sitting on a train slowly rolling out of the station, it can seem like it is the stationary train next to yours that is departing instead.

A handful of 14th-century scholastic thinkers wondered how this parallax effect came about. What explains our perceptual error? Let’s call this the problem of erring. In finding a solution, the medieval philosophers had to take into account another observation: nonhuman animals err too. According to scholastic orthodoxy, human and nonhuman animals were alike in being animals. Even so, within this category, humans occupied a special place: they are the only type of animal that is endowed with an intellect, a rational soul. They are, in medieval parlance, rational animals.

more here.

Friday Poem

At the Galleria Shopping Mall

Just past the bin of pastel baby socks and underwear,

there are some 49-dollar Chinese-made TVs;

one of them singing news about a far-off war,

one comparing the breast size of an actress from Hollywood

to the breast size of an actress from Bollywood.

And here is my niece Lucinda,

who is nine and a true daughter of Texas,

who has developed the flounce of a pedigreed blonde

and declares that her favorite sport is shopping.

Today is the day she embarks upon her journey,

swinging a credit card like a scythe

through the meadows of golden merchandise.

Today is the day she stops looking at faces,

and starts assessing the labels of purses;

So let it begin. Let her be dipped in the dazzling bounty

and raised and wrung out again and again.

And let us watch.

As the gods in olden stories

turned mortals into laurel trees and crows

to teach them some kind of lesson,

so we were turned into Americans

to learn something about loneliness.

by Tony Hoagland

from Poetry Magazine, July- August, 2009

Thursday, June 27, 2024

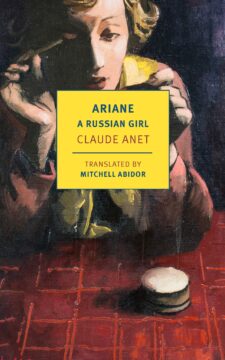

Ice queens, sex machines

Fiona Bell in the European Review of Books:

For some writers, some lovers, some readers, the physical and the verbal are the same. With erotica, I’ve found, there’s no way to lose. Best case scenario: you get turned on. Second best: you laugh. Worst case: you wonder why you didn’t get turned on or laugh, and you have a good think.

For some writers, some lovers, some readers, the physical and the verbal are the same. With erotica, I’ve found, there’s no way to lose. Best case scenario: you get turned on. Second best: you laugh. Worst case: you wonder why you didn’t get turned on or laugh, and you have a good think.

At first, I’d intended only to think. About all those femme fatales in Bond movies, the Georgian girls on the Beatles’ mi-mi-mi-mi-mi-mind, the internet ads for « Russian women in your area ». Where did all this come from? I set out to discover the history of Russia-themed porn, back to the nineteenth century at least, all those western writers fetishizing women from the Russian empire. Whether ice queens or sex machines, Russian women are touted as eastern philosophers of sexuality. To sleep with them is to unite East and West, to dissolve the mind-body divide, to extinguish the flame of the Enlightenment.

More here.