Max Krupnick in Harvard Magazine:

WHEN HAMAS TERRORISTS attacked Israel last October 7, they unleashed death and destruction—and also inflamed American prejudice on ethnic and religious grounds. Within hours, allegations of such bias came to Harvard. A hasty October 7 student letter holding “the Israeli regime entirely responsible for all unfolding violence” prompted immediate attacks on the presumed authors, and fierce denunciations of their alleged antisemitism, from within the University community and beyond. Much more was to come. In the two months following October 7, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) reported a 337 percent increase in antisemitic incidents nationwide. The campus tensions were further heightened following the December 5 hearing where members of Congress berated then-President Claudine Gay (alongside her MIT and University of Pennsylvania counterparts) for leading campuses the representatives deemed antisemitic.

WHEN HAMAS TERRORISTS attacked Israel last October 7, they unleashed death and destruction—and also inflamed American prejudice on ethnic and religious grounds. Within hours, allegations of such bias came to Harvard. A hasty October 7 student letter holding “the Israeli regime entirely responsible for all unfolding violence” prompted immediate attacks on the presumed authors, and fierce denunciations of their alleged antisemitism, from within the University community and beyond. Much more was to come. In the two months following October 7, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) reported a 337 percent increase in antisemitic incidents nationwide. The campus tensions were further heightened following the December 5 hearing where members of Congress berated then-President Claudine Gay (alongside her MIT and University of Pennsylvania counterparts) for leading campuses the representatives deemed antisemitic.

As the University’s task forces on combating antisemitism and combating anti-Muslim and anti-Arab bias press their work forward and prepare broad recommendations, two reports published on May 16 lay out political and alumni critiques of the Harvard campus climate. They present external and internal perspectives on antisemitism in the community, and argue that beyond individual incidents, the institution (its leadership, its administrative processes, and its curriculum) are themselves antisemitic. Published two days after the 20-day pro-Palestine encampment in the Old Yard ended, these reports represent some of the most pointed criticisms of the University arising from the events since October 7.

More here.

S

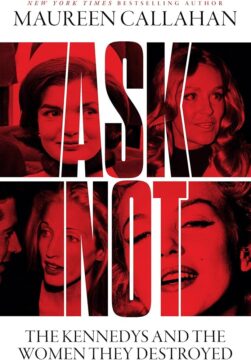

S In the opening sentence of her rage-swollen “Ask Not,” Maureen Callahan declares that her book “is not ideological or partisan.” It is, of course, both. Sometimes it is both in extremis. You need only cast an eye over its cover, which, like the book itself, is black and white and red all over. Bad men wronging good women: cheating on them, abandoning them, infecting them, turning them into alcoholics, leaving them for dead, raping and maiming and killing them.

In the opening sentence of her rage-swollen “Ask Not,” Maureen Callahan declares that her book “is not ideological or partisan.” It is, of course, both. Sometimes it is both in extremis. You need only cast an eye over its cover, which, like the book itself, is black and white and red all over. Bad men wronging good women: cheating on them, abandoning them, infecting them, turning them into alcoholics, leaving them for dead, raping and maiming and killing them. Immediately after the attack, a photograph circulated of Rushdie being wheeled to an emergency helicopter; the volume of blood and the places he was bleeding from didn’t look promising. The longer the information gap stretched, the eerier our preparation for a post-Rushdie world became, one we’d feared even after Iran effectively

Immediately after the attack, a photograph circulated of Rushdie being wheeled to an emergency helicopter; the volume of blood and the places he was bleeding from didn’t look promising. The longer the information gap stretched, the eerier our preparation for a post-Rushdie world became, one we’d feared even after Iran effectively  How children learn language has long been of interest to those concerned with its evolution. The idea that ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’ has been promoted, which means the stages of child development on their way to adulthood replicate those of our human ancestors on their way to becoming modern humans. This idea has been applied to language acquisition and its evolution, but I’ve never been persuaded. It is intellectually problematic because our human ancestors were never ‘on their way’ to anywhere other than being themselves. My interest in language acquisition is different and twofold.

How children learn language has long been of interest to those concerned with its evolution. The idea that ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’ has been promoted, which means the stages of child development on their way to adulthood replicate those of our human ancestors on their way to becoming modern humans. This idea has been applied to language acquisition and its evolution, but I’ve never been persuaded. It is intellectually problematic because our human ancestors were never ‘on their way’ to anywhere other than being themselves. My interest in language acquisition is different and twofold. So far as I can determine Ted Hughes never went shopping with Sylvia Plath. He thought her flair for fashion, and her materialistic desires, frivolous. “I need to curb my lust for buying dresses,” she wrote to herself on May 9, 1958 while the married couple were living in Northampton, Massachusetts. Four years later, on her own in London during her last days, she shopped like mad, threw away her country duds, reveled in a new hairdo, and enjoyed wolf whistles on the street. She had repressed a good deal of herself to please the man whose unkempt, often dirty appearance she had schooled herself to tolerate.

So far as I can determine Ted Hughes never went shopping with Sylvia Plath. He thought her flair for fashion, and her materialistic desires, frivolous. “I need to curb my lust for buying dresses,” she wrote to herself on May 9, 1958 while the married couple were living in Northampton, Massachusetts. Four years later, on her own in London during her last days, she shopped like mad, threw away her country duds, reveled in a new hairdo, and enjoyed wolf whistles on the street. She had repressed a good deal of herself to please the man whose unkempt, often dirty appearance she had schooled herself to tolerate. When it comes to gender equality, no society is perfect, but some are widely understood to have come further than others. These societies do a better job of offering equal opportunities, rights and responsibilities, and minimising structural power differences between men and women. One might expect that men and women in these societies would also become more similar to each other in terms of personality and other psychological qualities. Research has previously found differences in men’s and women’s average levels of characteristics such as

When it comes to gender equality, no society is perfect, but some are widely understood to have come further than others. These societies do a better job of offering equal opportunities, rights and responsibilities, and minimising structural power differences between men and women. One might expect that men and women in these societies would also become more similar to each other in terms of personality and other psychological qualities. Research has previously found differences in men’s and women’s average levels of characteristics such as