At the Galleria Shopping Mall

Just past the bin of pastel baby socks and underwear,

there are some 49-dollar Chinese-made TVs;

one of them singing news about a far-off war,

one comparing the breast size of an actress from Hollywood

to the breast size of an actress from Bollywood.

And here is my niece Lucinda,

who is nine and a true daughter of Texas,

who has developed the flounce of a pedigreed blonde

and declares that her favorite sport is shopping.

Today is the day she embarks upon her journey,

swinging a credit card like a scythe

through the meadows of golden merchandise.

Today is the day she stops looking at faces,

and starts assessing the labels of purses;

So let it begin. Let her be dipped in the dazzling bounty

and raised and wrung out again and again.

And let us watch.

As the gods in olden stories

turned mortals into laurel trees and crows

to teach them some kind of lesson,

so we were turned into Americans

to learn something about loneliness.

by Tony Hoagland

from Poetry Magazine, July- August, 2009

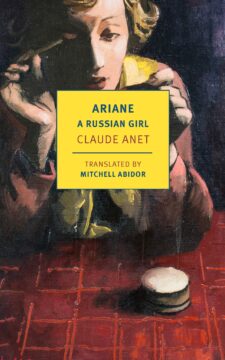

For some writers, some lovers, some readers, the physical and the verbal are the same. With erotica, I’ve found, there’s no way to lose. Best case scenario: you get turned on. Second best: you laugh. Worst case: you wonder why you didn’t get turned on or laugh, and you have a good think.

For some writers, some lovers, some readers, the physical and the verbal are the same. With erotica, I’ve found, there’s no way to lose. Best case scenario: you get turned on. Second best: you laugh. Worst case: you wonder why you didn’t get turned on or laugh, and you have a good think. Each summer, like clockwork, millions of beech trees throughout Europe sync up, tuning their reproductive physiology to one another. Within a matter of days, the trees produce all the seeds they’ll make for the year, then release their fruit onto the forest floor to create a new generation and feed the surrounding ecosystem.

Each summer, like clockwork, millions of beech trees throughout Europe sync up, tuning their reproductive physiology to one another. Within a matter of days, the trees produce all the seeds they’ll make for the year, then release their fruit onto the forest floor to create a new generation and feed the surrounding ecosystem. ‘I

‘I W

W WHAT IS A GOOD DEATH?

WHAT IS A GOOD DEATH? Over the last several decades, the digital revolution has changed nearly every aspect of our lives.

Over the last several decades, the digital revolution has changed nearly every aspect of our lives.  Taylor’s new book is formidably chewy, with page after page featuring passages of Hölderlin, Novalis, and Rilke, offered both in the original German and in translation. Long analyses of

Taylor’s new book is formidably chewy, with page after page featuring passages of Hölderlin, Novalis, and Rilke, offered both in the original German and in translation. Long analyses of  In Glynnis MacNicol’s second memoir,

In Glynnis MacNicol’s second memoir,

R

R You might have encountered Jehovah’s Witnesses before as the conservatively dressed religious types knocking on your front door, offering copies of The Watchtower, a free magazine promoting their faith. But there’s a darker side to this religious group, whose estimated 8 million members worldwide believe we are living in the “last days.” For the latest episode of

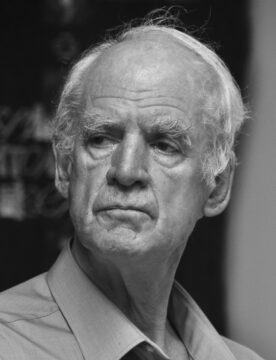

You might have encountered Jehovah’s Witnesses before as the conservatively dressed religious types knocking on your front door, offering copies of The Watchtower, a free magazine promoting their faith. But there’s a darker side to this religious group, whose estimated 8 million members worldwide believe we are living in the “last days.” For the latest episode of  The Medical Research Council’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) in Cambridge, UK, is a world leader in basic biology research. The lab’s list of breakthroughs is enviable, from the structure of DNA and proteins to genetic sequencing. Since its origins in the late 1940s, the institute — currently with around 700 staff members — has produced a dozen Nobel prizewinners, including DNA decipherers James Watson, Francis Crick and Fred Sanger. Four LMB scientists received their awards in the past 15 years:

The Medical Research Council’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) in Cambridge, UK, is a world leader in basic biology research. The lab’s list of breakthroughs is enviable, from the structure of DNA and proteins to genetic sequencing. Since its origins in the late 1940s, the institute — currently with around 700 staff members — has produced a dozen Nobel prizewinners, including DNA decipherers James Watson, Francis Crick and Fred Sanger. Four LMB scientists received their awards in the past 15 years:  There are two irrefutable axioms that can be made about jazz. The first is that jazz is America’s most significant cultural contribution to the world; the second is that jazz was mostly, though not entirely, a contribution born from the experience and brilliance of America’s Black populace who have rarely been treated as full citizens. Regarding the first claim, if the genre is not America’s “classical music,” for there is a bit of a category mistake in Wynton Marsalis’s contention which judges the music by such standards, then jazz is certainly the most indispensable and quintessential of American creations, surpassing in significance other novelties, from comic books to Hollywood films. Crouch describes Ellington, and by proxy jazz, as “maybe the most American of Americans,” even while the conservative critic was long an advocate for the music as being fundamentally our native “classical” (a role for which he was influential as Marsalis’s adviser as director of jazz at Lincoln Center). The desire to transform jazz into classical music—even my own comparison of Ellington to Bach—is an insulting reduction of the music’s innovation. Jazz doesn’t need to be classical music, it’s already jazz.

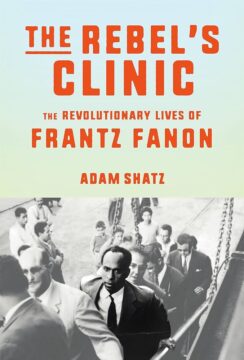

There are two irrefutable axioms that can be made about jazz. The first is that jazz is America’s most significant cultural contribution to the world; the second is that jazz was mostly, though not entirely, a contribution born from the experience and brilliance of America’s Black populace who have rarely been treated as full citizens. Regarding the first claim, if the genre is not America’s “classical music,” for there is a bit of a category mistake in Wynton Marsalis’s contention which judges the music by such standards, then jazz is certainly the most indispensable and quintessential of American creations, surpassing in significance other novelties, from comic books to Hollywood films. Crouch describes Ellington, and by proxy jazz, as “maybe the most American of Americans,” even while the conservative critic was long an advocate for the music as being fundamentally our native “classical” (a role for which he was influential as Marsalis’s adviser as director of jazz at Lincoln Center). The desire to transform jazz into classical music—even my own comparison of Ellington to Bach—is an insulting reduction of the music’s innovation. Jazz doesn’t need to be classical music, it’s already jazz. Fanon’s trickiness lies in how he seduces the reader with a moral outrage that he immediately deconstructs. Starting from a position of anti-colonial fury, his books ascend to a universalist crescendo. This can function like a trap for any reader who wants a monolithic Fanon, whether revolutionary or humanist, nationalist or internationalist, romantic or realist. Rather than stabilize him, we must allow him to be both—sometimes at once but at other times in progression. We must accept the dialectical Fanon, a thinker larger than the mutually defining opposites he described. To understand him, we cannot split him, as the psychiatrists would say. For in protecting Fanon from one aspect of himself, we ultimately end up trying to protect ourselves.

Fanon’s trickiness lies in how he seduces the reader with a moral outrage that he immediately deconstructs. Starting from a position of anti-colonial fury, his books ascend to a universalist crescendo. This can function like a trap for any reader who wants a monolithic Fanon, whether revolutionary or humanist, nationalist or internationalist, romantic or realist. Rather than stabilize him, we must allow him to be both—sometimes at once but at other times in progression. We must accept the dialectical Fanon, a thinker larger than the mutually defining opposites he described. To understand him, we cannot split him, as the psychiatrists would say. For in protecting Fanon from one aspect of himself, we ultimately end up trying to protect ourselves.