Bradley and Luskin in Evolution News:

In recent years, MIT physicist Jeremy England (pictured above) has gained media attention for proposing a thermodynamic energy-dissipation model of the origin of life. England’s view was summarized when he famously said that the origin and evolution of life “should be as unsurprising as rocks rolling downhill.” He continued, “You start with a random clump of atoms, and if you shine light on it for long enough, it should not be so surprising that you get a plant.”1Another physicist, ID theorist Brian Miller, has responded to England’s research.

In recent years, MIT physicist Jeremy England (pictured above) has gained media attention for proposing a thermodynamic energy-dissipation model of the origin of life. England’s view was summarized when he famously said that the origin and evolution of life “should be as unsurprising as rocks rolling downhill.” He continued, “You start with a random clump of atoms, and if you shine light on it for long enough, it should not be so surprising that you get a plant.”1Another physicist, ID theorist Brian Miller, has responded to England’s research.

Miller points out that the kind of energy that dissipates as a result of the sun shining on the Earth or other natural processes cannot explain how living systems have both low entropy (disorder) and high energy. As Miller puts it: “These are unnatural circumstances. Natural systems never both decrease in entropy and increase in energy — not at the same time.” Living cells do this “by employing complex molecular machinery and finely tuned chemical networks to convert one form of energy from the environment into high-energy molecules” — things that cannot be present prior to the origin of life because they must be explained by the origin of life. Without this cellular machinery to harness energy from the environment and drive down entropy, England’s energy-dissipation models cannot do the task they’ve been handed. As Miller said, England’s model cannot account for the origin of biological information, which “is essential for constructing and maintaining the cell’s structures and processes.”

More here.

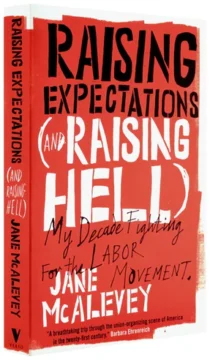

Raising Expectations is as much tell-all as organizing manual, but it was Jane’s second book, published in 2016—by an academic press, no less—that turned her into as much of a household name as any labor organizer can be in what she called “the new Gilded Age.”

Raising Expectations is as much tell-all as organizing manual, but it was Jane’s second book, published in 2016—by an academic press, no less—that turned her into as much of a household name as any labor organizer can be in what she called “the new Gilded Age.”

Stephen King, Min Jin Lee, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Bonnie Garmus, Nana Kwame Adjei‑Brenyah, Junot Díaz, Sarah Jessica Parker, James Patterson, Elin Hilderbrand, Annette Gordon‑Reed, Rebecca Roanhorse, Marlon James, Roxane Gay, Jonathan Lethem, Sarah MacLean, Ed Yong, Thomas Chatterton Williams, Paul Tremblay, Nick Hornby, Scott Turow, Daniel Alarcón, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Lucy Sante, Gary Shteyngart, Anand Giridharadas, Jessamine Chan, Michael Robbins, Alma Katsu, Megan Abbott, Joshua Ferris, Ann Napolitano, John Irving, Tiya Miles, Jami Attenberg, Stephen L. Carter, Sarah Schulman, Elizabeth Hand, Dion Graham, Jeremy Denk, Morgan Jerkins, Michael Roth & Ryan Holiday.

Stephen King, Min Jin Lee, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Bonnie Garmus, Nana Kwame Adjei‑Brenyah, Junot Díaz, Sarah Jessica Parker, James Patterson, Elin Hilderbrand, Annette Gordon‑Reed, Rebecca Roanhorse, Marlon James, Roxane Gay, Jonathan Lethem, Sarah MacLean, Ed Yong, Thomas Chatterton Williams, Paul Tremblay, Nick Hornby, Scott Turow, Daniel Alarcón, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Lucy Sante, Gary Shteyngart, Anand Giridharadas, Jessamine Chan, Michael Robbins, Alma Katsu, Megan Abbott, Joshua Ferris, Ann Napolitano, John Irving, Tiya Miles, Jami Attenberg, Stephen L. Carter, Sarah Schulman, Elizabeth Hand, Dion Graham, Jeremy Denk, Morgan Jerkins, Michael Roth & Ryan Holiday. Over several years now, a single question has refused to leave me: what is beauty? Triggering it was a series of aesthetic experiences so intense that I count them among the most significant moments of my life. They felt supercharged with meaning, yet what they meant I could not tell. After a couple years of scratching my head, I still cannot claim to understand them. Nevertheless, I believe I have taken a step towards understanding what beauty is.

Over several years now, a single question has refused to leave me: what is beauty? Triggering it was a series of aesthetic experiences so intense that I count them among the most significant moments of my life. They felt supercharged with meaning, yet what they meant I could not tell. After a couple years of scratching my head, I still cannot claim to understand them. Nevertheless, I believe I have taken a step towards understanding what beauty is. For weeks, pundits have been speculating that France’s snap legislative election could blow up in President Emmanuel Macron’s face—and boy did it. Only it’s blown up in a way nobody expected. Instead of the much-feared far right victory, the election will probably force the centrist president into an awkward coalition with the left, an exercise likely to leave both sides badly bruised.

For weeks, pundits have been speculating that France’s snap legislative election could blow up in President Emmanuel Macron’s face—and boy did it. Only it’s blown up in a way nobody expected. Instead of the much-feared far right victory, the election will probably force the centrist president into an awkward coalition with the left, an exercise likely to leave both sides badly bruised. ‘Why did you decide to study philosophy?’ asked the Harvard professor, sitting in the park in his cream linen suit.

‘Why did you decide to study philosophy?’ asked the Harvard professor, sitting in the park in his cream linen suit. Anyone who’d like to look a Nazi in the eye is working against the clock. An eighteen-year-old member of the Nazi Party in 1945 would now be coming up to a hundred. Soon there will be none left. When the film director Luke Holland was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2015, he was interviewing the last surviving Nazis to build an archive of their first-hand accounts of complicity. He kept going as his health declined. One of my colleagues was Holland’s haematologist, and a few of us were invited to watch some unedited footage of German nonagenarians in dowdy sitting-rooms recounting, with nostalgia, unease or insouciance, their involvement in the operation of the Nazi state. Afterwards, another colleague broke our stunned silence with the remark: ‘There but for the grace of God go I.’ At first I thought she meant we were lucky to have not been Jewish, disabled, Romani or gay in Germany in the 1930s, but she meant we were lucky not to have been Nazis.

Anyone who’d like to look a Nazi in the eye is working against the clock. An eighteen-year-old member of the Nazi Party in 1945 would now be coming up to a hundred. Soon there will be none left. When the film director Luke Holland was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2015, he was interviewing the last surviving Nazis to build an archive of their first-hand accounts of complicity. He kept going as his health declined. One of my colleagues was Holland’s haematologist, and a few of us were invited to watch some unedited footage of German nonagenarians in dowdy sitting-rooms recounting, with nostalgia, unease or insouciance, their involvement in the operation of the Nazi state. Afterwards, another colleague broke our stunned silence with the remark: ‘There but for the grace of God go I.’ At first I thought she meant we were lucky to have not been Jewish, disabled, Romani or gay in Germany in the 1930s, but she meant we were lucky not to have been Nazis. One June afternoon, I found myself idling about a meadow at the top of a forest in the northwest of the Pacific Northwest. I ate a rough lunch and slept, hands in pockets and cap on face. When I awoke, the sun was still high and the bees buzzed and the meadow kept its drowsiness on me—and so I opened a book of essays I’d been carrying around for the better part of a week and turned to Henry David Thoreau’s 1862 essay “

One June afternoon, I found myself idling about a meadow at the top of a forest in the northwest of the Pacific Northwest. I ate a rough lunch and slept, hands in pockets and cap on face. When I awoke, the sun was still high and the bees buzzed and the meadow kept its drowsiness on me—and so I opened a book of essays I’d been carrying around for the better part of a week and turned to Henry David Thoreau’s 1862 essay “ In 19th century New York City, Theodore Gaillard Thomas enjoyed an unusual level of fame for a gynecologist. The reason, oddly enough, was milk. Between 1873 and 1880, the daring idea of transfusing milk into the body as a substitute for blood was being tested across the United States. Thomas was the most outspoken advocate of the practice.

In 19th century New York City, Theodore Gaillard Thomas enjoyed an unusual level of fame for a gynecologist. The reason, oddly enough, was milk. Between 1873 and 1880, the daring idea of transfusing milk into the body as a substitute for blood was being tested across the United States. Thomas was the most outspoken advocate of the practice. EMILY NUSSBAUM, THE PULITZER-WINNING television critic and New Yorker staff writer, ends her well-researched, somewhat grueling book on the history of reality television, Cue the Sun!, with a reminder that critics have historically dismissed reality TV as a fad. Yet reality TV has not gone away. It’s more than just a fad, she writes, because “in the end, all our faces got stuck that way.”

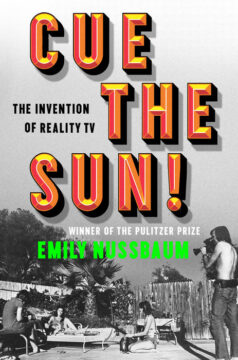

EMILY NUSSBAUM, THE PULITZER-WINNING television critic and New Yorker staff writer, ends her well-researched, somewhat grueling book on the history of reality television, Cue the Sun!, with a reminder that critics have historically dismissed reality TV as a fad. Yet reality TV has not gone away. It’s more than just a fad, she writes, because “in the end, all our faces got stuck that way.” In early May, Google announced it would be adding artificial intelligence to its search engine. When the new feature rolled out,

In early May, Google announced it would be adding artificial intelligence to its search engine. When the new feature rolled out,  In early 1824, 30 members of Vienna’s music community sent a letter to Ludwig van Beethoven

In early 1824, 30 members of Vienna’s music community sent a letter to Ludwig van Beethoven  F

F WHEN HAMAS TERRORISTS

WHEN HAMAS TERRORISTS