Ellyn Gaydos at Harper’s Magazine:

On a tour of Barre’s E. L. Smith quarry, one of the deepest working granite quarries in the world, Roger, a thirty-five-year veteran of the operation, led us past piles of grout to a fence. We looked over it and down into the nearly six-hundred-foot-deep hole, where the machines and their sounds, the whine of the saws and the belch of dump trucks, were more readily apparent than any human presence. The quarry was not one deep hole but a series of descending plateaus. Plants clung to the rock that gave way to penetratingly blue water that had collected in the basin, the chalky granite dust turning the pool into a false image of glacial melt. Our guide told us that in 1970, when he began working in the hole, he was one of two hundred men. Today there are only thirteen. If they were to keep going at this rate, they could continue to quarry here for the next 4,500 years. Roger told us that the company that owns the quarry will not dig any deeper—the pressure builds the farther down they go, and could begin to crack the stone—so instead they shave away at the sides of the opening. These formations were created approximately 330 million years ago, as magma from below the mantle rose and cooled. The result is uniquely uniform plugs of hard, clean-breaking Barre granite, one of the densest of carvable rocks. It bears distinct smudges of white and coal-black shavings, marred by nicks of gray and glassy dots of quartz. Combined, these minerals give the stone an indistinct solidity, as if seen through a blurred lens. Its sparkle comes from the mica exposed by a carver’s chisel.

On a tour of Barre’s E. L. Smith quarry, one of the deepest working granite quarries in the world, Roger, a thirty-five-year veteran of the operation, led us past piles of grout to a fence. We looked over it and down into the nearly six-hundred-foot-deep hole, where the machines and their sounds, the whine of the saws and the belch of dump trucks, were more readily apparent than any human presence. The quarry was not one deep hole but a series of descending plateaus. Plants clung to the rock that gave way to penetratingly blue water that had collected in the basin, the chalky granite dust turning the pool into a false image of glacial melt. Our guide told us that in 1970, when he began working in the hole, he was one of two hundred men. Today there are only thirteen. If they were to keep going at this rate, they could continue to quarry here for the next 4,500 years. Roger told us that the company that owns the quarry will not dig any deeper—the pressure builds the farther down they go, and could begin to crack the stone—so instead they shave away at the sides of the opening. These formations were created approximately 330 million years ago, as magma from below the mantle rose and cooled. The result is uniquely uniform plugs of hard, clean-breaking Barre granite, one of the densest of carvable rocks. It bears distinct smudges of white and coal-black shavings, marred by nicks of gray and glassy dots of quartz. Combined, these minerals give the stone an indistinct solidity, as if seen through a blurred lens. Its sparkle comes from the mica exposed by a carver’s chisel.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

This is the third of a trio of reviews in which I take a brief detour into ants and collective behaviour more generally. I previously reviewed

This is the third of a trio of reviews in which I take a brief detour into ants and collective behaviour more generally. I previously reviewed  I

I Ashura is marked on the 10th day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar, by all Muslims. It marks the day Nuh (Noah) left the Ark and the day Musa (Moses) was saved from the Pharaoh of Egypt by God. The Prophet Muhammad used to fast on Ashura in Mecca, where it became a common tradition for the early Muslims. Ashura this year will be marked in most places on August 29. But for the Shia, it is also a major religious event to commemorate the martyrdom of Husayn Ibn Ali al-Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, who died at the Battle of Karbala in 680 AD.

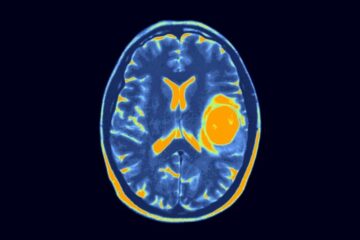

Ashura is marked on the 10th day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar, by all Muslims. It marks the day Nuh (Noah) left the Ark and the day Musa (Moses) was saved from the Pharaoh of Egypt by God. The Prophet Muhammad used to fast on Ashura in Mecca, where it became a common tradition for the early Muslims. Ashura this year will be marked in most places on August 29. But for the Shia, it is also a major religious event to commemorate the martyrdom of Husayn Ibn Ali al-Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, who died at the Battle of Karbala in 680 AD. Every two weeks at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Washington, a five-year-old child stops by for a fresh dose of genetically engineered immune cells administered directly into the fluid around their brain.

Every two weeks at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Washington, a five-year-old child stops by for a fresh dose of genetically engineered immune cells administered directly into the fluid around their brain. Robinson opens

Robinson opens  WHY WOULD A

WHY WOULD A  Melinda and I sometimes read the same book at the same time. It’s usually a lot of fun, but it can get us in trouble when one of us is further along than the other—which recently happened when we were both reading A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles. At one point, I got teary-eyed because one of the characters gets hurt and must go to the hospital. Melinda was a couple chapters behind me. When she saw me crying, she became worried that a character she loved was going to die. I didn’t want to spoil anything for her, so I just had to wait until she caught up to me.

Melinda and I sometimes read the same book at the same time. It’s usually a lot of fun, but it can get us in trouble when one of us is further along than the other—which recently happened when we were both reading A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles. At one point, I got teary-eyed because one of the characters gets hurt and must go to the hospital. Melinda was a couple chapters behind me. When she saw me crying, she became worried that a character she loved was going to die. I didn’t want to spoil anything for her, so I just had to wait until she caught up to me.