Tom Zoellner at the LARB:

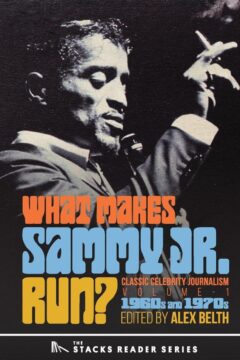

Editor Alex Belth has created an unusual literary anthology of some of the best celebrity magazine profiles from 1959 to 1979, what is generally regarded—at least by publishing old-timers—as the peak years of the genre, before the ferret-faced publicists cracked down on honesty and budgets ran dry. What Makes Sammy Jr. Run? Classic Celebrity Journalism Volume 1 (1960s and 1970s), published by the Sager Group this spring, puts 18 long-form stories about well-known actors, writers, and musicians into one place. The result is like a walk through a delightful museum of postwar America, with all its bright spots and faults.

Editor Alex Belth has created an unusual literary anthology of some of the best celebrity magazine profiles from 1959 to 1979, what is generally regarded—at least by publishing old-timers—as the peak years of the genre, before the ferret-faced publicists cracked down on honesty and budgets ran dry. What Makes Sammy Jr. Run? Classic Celebrity Journalism Volume 1 (1960s and 1970s), published by the Sager Group this spring, puts 18 long-form stories about well-known actors, writers, and musicians into one place. The result is like a walk through a delightful museum of postwar America, with all its bright spots and faults.

The nostalgia for a lost era runs even thicker. Not only have celebrity profiles gotten flatter and duller—the canned hotel room conversation hardly makes for fun reading—but the entire medium of magazines has also taken serious economic blows and thinned out. Celebrities now do more direct and manageable communications with their fans through social media. Who needs to invite the annoying writer, that jealous guttersnipe hiding a knife in their back pocket?

more here.

In the course of human events, America has come to agree on one thing: that any modern birthday celebration of itself will involve sizzling hunks of meat, Springsteen in the ears, smoke in the eyes, sulfur in the nostrils, rockets’ red glare.

In the course of human events, America has come to agree on one thing: that any modern birthday celebration of itself will involve sizzling hunks of meat, Springsteen in the ears, smoke in the eyes, sulfur in the nostrils, rockets’ red glare. When Angela received her first shot at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in early 2020, Covid-19 was months away. Far from a household name, mRNA vaccines were mostly relegated to lab studies. Yet the jab she received was made of the same technology. A melanoma patient, Angela had multiple malignant moles removed. Alongside an established immune-stimulating drug, the hope was the duo could fight off any residual cancerous cells and slash the chances of relapse. Scientists have long sought cancer vaccines that prevent the pesky cells from growing back. Like those targeting viruses, the vaccines would train the body’s immune system to recognize the cancerous cells and attack and eliminate them before they could grow and spread. Despite decades of research into cancer vaccines, the dream has mostly failed. One reason is that every cancer, in every person, is different. So is each person’s immune system. Tailoring vaccines to neutralize cancers for each patient would not only be expensive, but sometimes impossible due to how long they’d take to develop—time is not on cancer patients’ sides.

When Angela received her first shot at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in early 2020, Covid-19 was months away. Far from a household name, mRNA vaccines were mostly relegated to lab studies. Yet the jab she received was made of the same technology. A melanoma patient, Angela had multiple malignant moles removed. Alongside an established immune-stimulating drug, the hope was the duo could fight off any residual cancerous cells and slash the chances of relapse. Scientists have long sought cancer vaccines that prevent the pesky cells from growing back. Like those targeting viruses, the vaccines would train the body’s immune system to recognize the cancerous cells and attack and eliminate them before they could grow and spread. Despite decades of research into cancer vaccines, the dream has mostly failed. One reason is that every cancer, in every person, is different. So is each person’s immune system. Tailoring vaccines to neutralize cancers for each patient would not only be expensive, but sometimes impossible due to how long they’d take to develop—time is not on cancer patients’ sides. Shortly before his death in 1974, R C Zaehner, Spalding Professor of Eastern Religions and Ethics at Oxford, observed that young Westerners who had turned away from Christianity were more often drawn to the religions of India and the Far East than to Islam. ‘The young’, the devoutly Catholic Zaehner stated, ‘are not interested in switching from one dogmatic monotheistic faith to another: hence they are little interested in Islam except when Islam itself is turned upside down and becomes Sufism, which in its developed form is barely distinguishable from Vedanta.’ ‘Indeed,’ he went on, ‘that egregious populariser Idries Shah has gone so far as to claim Zen as a manifestation of Sufism.’ This, Zaehner declared, was historical ‘nonsense’ and academically ‘detestable’.

Shortly before his death in 1974, R C Zaehner, Spalding Professor of Eastern Religions and Ethics at Oxford, observed that young Westerners who had turned away from Christianity were more often drawn to the religions of India and the Far East than to Islam. ‘The young’, the devoutly Catholic Zaehner stated, ‘are not interested in switching from one dogmatic monotheistic faith to another: hence they are little interested in Islam except when Islam itself is turned upside down and becomes Sufism, which in its developed form is barely distinguishable from Vedanta.’ ‘Indeed,’ he went on, ‘that egregious populariser Idries Shah has gone so far as to claim Zen as a manifestation of Sufism.’ This, Zaehner declared, was historical ‘nonsense’ and academically ‘detestable’. Writing under the shadow of Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha, Kadare examined contemporary society through the lens of allegory and myth in novels including The General of the Dead Army, The Siege and The Palace of Dreams. After fleeing to Paris just months before Albania’s communist government collapsed in 1990, his reputation continued to grow as he kept returning to the region in his fiction. Translated into more than 40 languages, he won a series of awards including the Man Booker International prize.

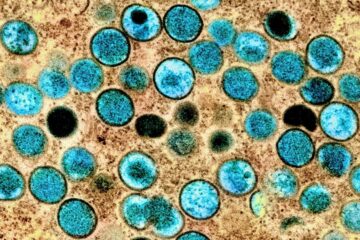

Writing under the shadow of Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha, Kadare examined contemporary society through the lens of allegory and myth in novels including The General of the Dead Army, The Siege and The Palace of Dreams. After fleeing to Paris just months before Albania’s communist government collapsed in 1990, his reputation continued to grow as he kept returning to the region in his fiction. Translated into more than 40 languages, he won a series of awards including the Man Booker International prize. Urgent action is needed to try to contain the spread of a new strain of mpox transmitted mainly by heterosexual sex that has caused more than 1000 cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, say health experts dealing with the outbreak. They fear the condition is poised to spread to neighbouring countries and possibly further afield.

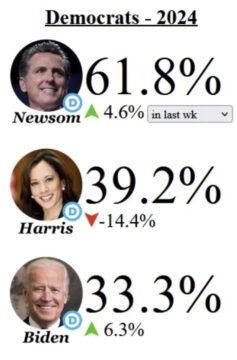

Urgent action is needed to try to contain the spread of a new strain of mpox transmitted mainly by heterosexual sex that has caused more than 1000 cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, say health experts dealing with the outbreak. They fear the condition is poised to spread to neighbouring countries and possibly further afield. Some of the party’s problems are hard and have no shortcuts. But the big one – figuring out whether replacing Biden would even help the Democrats’ electoral chances – is a good match for prediction markets. Set up markets to find the probability of Democrats winning they nominate Biden, vs. the probability of Democrats winning if they replace him with someone else.

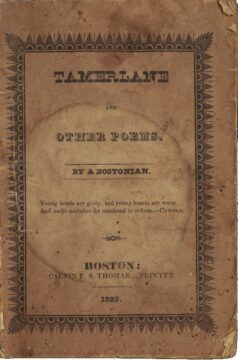

Some of the party’s problems are hard and have no shortcuts. But the big one – figuring out whether replacing Biden would even help the Democrats’ electoral chances – is a good match for prediction markets. Set up markets to find the probability of Democrats winning they nominate Biden, vs. the probability of Democrats winning if they replace him with someone else. My first personal encounter with the rarest book in American literature was memorable, even moving, for many reasons, but its physical appearance wasn’t one of them. If ever a book ought not to be judged by its cover, Edgar Allan Poe’s debut collection, Tamerlane and Other Poems, is that book. Known as the Black Tulip, only twelve copies appear to have survived since its publication in July 1827. That one of the last two in private hands is coming to auction this month, not quite two centuries later, marks an historic bibliophilic event.

My first personal encounter with the rarest book in American literature was memorable, even moving, for many reasons, but its physical appearance wasn’t one of them. If ever a book ought not to be judged by its cover, Edgar Allan Poe’s debut collection, Tamerlane and Other Poems, is that book. Known as the Black Tulip, only twelve copies appear to have survived since its publication in July 1827. That one of the last two in private hands is coming to auction this month, not quite two centuries later, marks an historic bibliophilic event. Around

Around  Scientists now know that stress is intimately linked with many chronic diseases: It can drive immune changes and inflammation in the body that can worsen symptoms of conditions like asthma, heart disease, arthritis, lupus and inflammatory bowel disease. Meanwhile, many issues caused by stress — headaches, heartburn, blood pressure problems, mood changes — can also be symptoms of chronic illnesses.

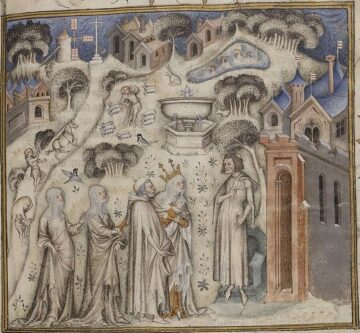

Scientists now know that stress is intimately linked with many chronic diseases: It can drive immune changes and inflammation in the body that can worsen symptoms of conditions like asthma, heart disease, arthritis, lupus and inflammatory bowel disease. Meanwhile, many issues caused by stress — headaches, heartburn, blood pressure problems, mood changes — can also be symptoms of chronic illnesses. Guillaume de Machaut, the master poet-composer of fourteenth-century France, served for many years as the canon of the great Gothic cathedral at Reims, where the kings of the realm were crowned. Machaut’s most famous creation, the Messe de Nostre Dame, has a singular place in musical history, because it is an early attempt at creating a comparably sublime edifice in sound—a six-movement work in four-part polyphony, lasting well over half an hour, in which austere, granitic harmony is set against delicate contrapuntal play and spiky rhythmic motion. This Mass is, in fact, the oldest extant piece of its type to have been attributed to a single composer. When, the other day, the San Francisco-based vocal ensemble Chanticleer sang it at Grace Cathedral, on Nob Hill, a suitable atmosphere of awe accumulated.

Guillaume de Machaut, the master poet-composer of fourteenth-century France, served for many years as the canon of the great Gothic cathedral at Reims, where the kings of the realm were crowned. Machaut’s most famous creation, the Messe de Nostre Dame, has a singular place in musical history, because it is an early attempt at creating a comparably sublime edifice in sound—a six-movement work in four-part polyphony, lasting well over half an hour, in which austere, granitic harmony is set against delicate contrapuntal play and spiky rhythmic motion. This Mass is, in fact, the oldest extant piece of its type to have been attributed to a single composer. When, the other day, the San Francisco-based vocal ensemble Chanticleer sang it at Grace Cathedral, on Nob Hill, a suitable atmosphere of awe accumulated. There are three tiers in the hierarchy of men’s professional tennis. The ATP Tour is the sport’s top division, the preserve of the top 100 male tennis players in the world. The Challenger Tour is populated mainly by players ranked between 100 and 300 in the world. Below that is the Futures tour, tennis’s vast netherworld of more than 2,000 true prospects and hopeless dreamers.

There are three tiers in the hierarchy of men’s professional tennis. The ATP Tour is the sport’s top division, the preserve of the top 100 male tennis players in the world. The Challenger Tour is populated mainly by players ranked between 100 and 300 in the world. Below that is the Futures tour, tennis’s vast netherworld of more than 2,000 true prospects and hopeless dreamers. In an instant, the protein folding problem had gone from impossible to painless. The success of artificial intelligence where the human mind had floundered rocked the community of biologists. “I was in shock,” said

In an instant, the protein folding problem had gone from impossible to painless. The success of artificial intelligence where the human mind had floundered rocked the community of biologists. “I was in shock,” said  I first read

I first read  Glenn Loury has been one of the most arresting voices on the fraught topic of race in the United States over the past four decades. Now in his mid-seventies (he was born in 1948), he produces a rich and prolific digital output of interviews, debates, and essays on

Glenn Loury has been one of the most arresting voices on the fraught topic of race in the United States over the past four decades. Now in his mid-seventies (he was born in 1948), he produces a rich and prolific digital output of interviews, debates, and essays on