Christmas Mail

By Ted Kooser

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

By Ted Kooser

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Phil Christman at The Hedgehog Review:

John J. Lennon is, at the moment, probably this country’s foremost imprisoned journalist. This title won’t be taken from him any time soon, not because there aren’t many talented and inquisitive people in prison but because the barriers to entry are so nearly impassible. A journalist’s life is a daunting prospect these days even to a person with freedom of movement, a real computer, the ability to make phone calls in private. Lennon’s new book, The Tragedy of True Crime, concludes with an author’s note that describes the makeshifts that he and his supporters have had to adopt so he can fulfill the most basic parts of an author’s job:

John J. Lennon is, at the moment, probably this country’s foremost imprisoned journalist. This title won’t be taken from him any time soon, not because there aren’t many talented and inquisitive people in prison but because the barriers to entry are so nearly impassible. A journalist’s life is a daunting prospect these days even to a person with freedom of movement, a real computer, the ability to make phone calls in private. Lennon’s new book, The Tragedy of True Crime, concludes with an author’s note that describes the makeshifts that he and his supporters have had to adopt so he can fulfill the most basic parts of an author’s job:

Receiving a 100,000-word work-in-progress manuscript in prison is harder than you may think, especially when that prison system is dealing with a K2 crisis. The drug looks like a regular piece of paper to the unknowing eye, but one sheet sprayed with K2 chemicals is worth about $1000 in prison.…

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Elizabeth Gibney in Nature:

In January this year, an announcement from China rocked the world of artificial intelligence. The firm DeepSeek released its powerful but cheap R1 model out of the blue — instantly demonstrating that the United States was not as far ahead in AI as many experts had thought.

In January this year, an announcement from China rocked the world of artificial intelligence. The firm DeepSeek released its powerful but cheap R1 model out of the blue — instantly demonstrating that the United States was not as far ahead in AI as many experts had thought.

Behind the bombshell announcement is Liang Wenfeng, a 40-year-old former financial analyst who is thought to have made millions of dollars applying AI algorithms to the stock market before using the cash in 2023 to establish DeepSeek, based in Hangzhou. Liang avoids the limelight and has given only a handful of interviews to the Chinese press (he declined a request to speak to Nature).

Liang’s models are as open as he is secretive. R1 is a ‘reasoning’ large language model (LLM) that excels at solving complex tasks — such as in mathematics and coding — by breaking them down into steps. It was the first of its kind to be released as open weight, meaning that the model can be downloaded and built on for free, so has been a boon for researchers who want to adapt algorithms to their own field. DeepSeek’s success seems to have prompted other companies in China and the United States to follow suit by releasing their own open models.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Enrich, Steve Eder, Jessica Silver-Greenberg, and Matthew Goldstein in the New York Times:

One evening in early 1976, a bushy-haired Jeffrey Epstein showed up for an event at an art gallery in Midtown Manhattan. Epstein was a math and physics teacher at the city’s prestigious Dalton School, and the father of one of his students had invited him. Epstein initially demurred, saying he didn’t go out much, but eventually relented. It would turn out to be one of the best decisions he ever made.

One evening in early 1976, a bushy-haired Jeffrey Epstein showed up for an event at an art gallery in Midtown Manhattan. Epstein was a math and physics teacher at the city’s prestigious Dalton School, and the father of one of his students had invited him. Epstein initially demurred, saying he didn’t go out much, but eventually relented. It would turn out to be one of the best decisions he ever made.

At the gallery, Epstein bumped into another Dalton parent, who had heard tales of the 23-year-old’s wondrous math skills. The parent asked if he’d ever thought about a job on Wall Street, according to an unreleased recording of Epstein and a document prepared by his lawyers. Epstein was game. The parent dialed a friend: Ace Greenberg, a top executive at Bear Stearns. Epstein, the friend told Greenberg, was “wasting his time at Dalton.”

Greenberg invited Epstein to the investment firm’s offices at 55 Water Street at the southern tip of Manhattan.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Bilge Ebiri in The Yale Review:

In the winter of 2024, the photographer and filmmaker RaMell Ross released Nickel Boys, a masterful adaptation of a novel by Colson Whitehead. In a fragmentary, impressionistic style, the film portrays the friendship of two African American teens at a brutal Florida reform academy during the Jim Crow era. Acclaimed as a visionary movie, it ended up on many critics’ best-of-the-year lists and earned an Oscar nomination for Best Picture.

In the winter of 2024, the photographer and filmmaker RaMell Ross released Nickel Boys, a masterful adaptation of a novel by Colson Whitehead. In a fragmentary, impressionistic style, the film portrays the friendship of two African American teens at a brutal Florida reform academy during the Jim Crow era. Acclaimed as a visionary movie, it ended up on many critics’ best-of-the-year lists and earned an Oscar nomination for Best Picture.

Ross is a fiercely independent artist. His first film, the lyrical 2018 documentary Hale County This Morning, This Evening, was also nominated for an Oscar. Afterward, he refused Hollywood’s overtures for years. So why did he take a meeting with the producers who reached out to him about making a studio-financed, big-budget adaptation of Nickel Boys? Ross’s explanation was simple: because one of them had produced Terrence Malick’s 2011 film, The Tree of Life. Ross’s reverence for Malick is plain in his films, which, like Malick’s, rely on extended montages of the everyday and do away with the conventional rules of cinematic storytelling, hovering instead between distant, melancholy reverie and hyperfocused, lived-in specificity. And he is not the only recent filmmaker who has fallen under Malick’s spell. Indeed, Malick’s sensibility, visual style, and working methods have had a profound influence on some of today’s best and most interesting directors.

Take Chloé Zhao, the director of the Oscar-winning Nomadland (2020). Her early films, all set in the American heartland, were regularly compared to Malick’s, and she herself pointed to The Tree of Life and Malick’s 2005 film, The New World, as influences on her 2021 Marvel superhero movie, Eternals. Those overtones persist in her latest, Hamnet, a film about the death of William Shakespeare’s only son and his subsequent creation of Hamlet. The movie may take place in Elizabethan England, but it is replete with lyrical passages and visions of nature that recall Malick’s work.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Andrew Cockburn in Harper’s Magazine:

On a cool evening in October, six weeks after Charlie Kirk was assassinated in full view of thousands at Utah Valley University, I joined a sea of young people lining up outside the auditorium on Indiana University’s sprawling Bloomington campus for an event sponsored by Kirk’s organization, Turning Point USA. Kirk himself had been scheduled to headline the event, one stop on a planned tour of colleges across the country. Instead we would hear from Tucker Carlson, once the star of Fox News and now a wildly popular podcast host. The choice was a pointed one given Carlson’s willingness to buck Republican orthodoxy, particularly on matters of foreign policy. He has vehemently denounced American military involvement abroad, including attacks on Iran, support for Ukraine, and most controversially, the U.S.-backed war in Gaza.

On a cool evening in October, six weeks after Charlie Kirk was assassinated in full view of thousands at Utah Valley University, I joined a sea of young people lining up outside the auditorium on Indiana University’s sprawling Bloomington campus for an event sponsored by Kirk’s organization, Turning Point USA. Kirk himself had been scheduled to headline the event, one stop on a planned tour of colleges across the country. Instead we would hear from Tucker Carlson, once the star of Fox News and now a wildly popular podcast host. The choice was a pointed one given Carlson’s willingness to buck Republican orthodoxy, particularly on matters of foreign policy. He has vehemently denounced American military involvement abroad, including attacks on Iran, support for Ukraine, and most controversially, the U.S.-backed war in Gaza.

The political and religious cast of the crowd in Bloomington was signaled by the street vendors, who were doing brisk business offering red, white, and black make america great again hats, along with caps proclaiming jesus won and sweatshirts emblazoned with freedom and Kirk’s signature. In the center of the plaza outside the venue, hand-lettered signs proclaimed christian values? israel massacres innocents and would jesus ignore this? will you? Pointing to the signs, I asked Dane, a young self-described Christian who declined to give his last name, whether he agreed with their message. “We’ve heard for a few years how the left feels about it,” he told me. “But you’re starting to see a little bit of a change in the right. They’ve spent many, many years trying to get a common consensus belief that Israel is one of our very best allies, and that belief is starting to change. It’s not just a niche thing anymore. I would be quite concerned if I was a politician.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rachel Wetzler at Artforum:

If nothing else, 2025 was a good year for demented painting. This might have been obvious to anyone who saw Laura Owens’s maximalist fantasia at Matthew Marks in Chelsea this past spring—the single best gallery show I saw all year. The works on view deployed all manner of painterly illusion, trick, and gag. Giant canvases hung in the main space, their collage-like compositions built up from dense aggregates of silk-screened layers (over a hundred in some cases). These were set against artist-made wallpaper, with a trompe l’oeil border of pretzels, donuts, and assorted other confections dangling from electrical cords whose dainty loops were modeled after trailing vines. Hidden behind a false door was a wraparound installation of paintings on aluminum panel configured as a mural, featuring a grab bag of floriated patterns jostling and colliding, with miniature canvases intermittently popping out of trapdoors like cuckoo clocks. Throughout this madcap ensemble, Owens made liberal use of flatly painted drop shadows that introduced a confounding fictive depth, alongside exaggerated instances of real depth—fluffy pastel dollops and smears of paint with the consistency of buttercream projecting off the surface. At room-size scale, the combination was as destabilizing as it was ridiculous.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Andrea Branchi at Aeon Magazine:

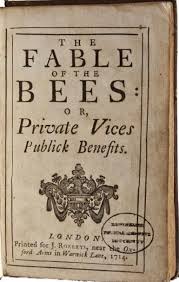

In 1714, and in an enlarged edition in 1723, Mandeville published the prose volume that made him infamous: The Fable of the Bees: Or, Private Vices, Public Benefits. The original poem was reprinted with a series of commentary essays in which Mandeville expanded upon his provocative arguments that human beings are self-interested, governed by their passions rather than their reason, and he offered an explanation of the origin of morality based solely on human sensitivity to praise and fear of shame through a rhapsody of social vignettes. Mandeville confronted his contemporaries with the disturbing fact that passions and habits commonly denounced as vices actually generate the welfare of a society.

In 1714, and in an enlarged edition in 1723, Mandeville published the prose volume that made him infamous: The Fable of the Bees: Or, Private Vices, Public Benefits. The original poem was reprinted with a series of commentary essays in which Mandeville expanded upon his provocative arguments that human beings are self-interested, governed by their passions rather than their reason, and he offered an explanation of the origin of morality based solely on human sensitivity to praise and fear of shame through a rhapsody of social vignettes. Mandeville confronted his contemporaries with the disturbing fact that passions and habits commonly denounced as vices actually generate the welfare of a society.

The idea that self-interested individuals, driven by their own desires, act independently to realise goods and institutions made The Fable of the Bees one of the chief literary sources of the laissez-faire doctrine. It is central to the economic concept of the market. In 1966, the free-market evangelist Friedrich von Hayek offered an enthusiastic reading of Mandeville that anointed the poet as an early theorist of the harmony of interests in a free market economy, a scheme that Hayek claimed was later expanded on by Adam Smith, reworking Mandeville’s paradox of ‘private vices, public benefits’ into the profoundly influential metaphor of the invisible hand. Today, Mandeville is standardly thought of as an economic thinker.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

It was beginning winter,

An in-between time,

The landscape still partly brown:

The bones of weeds kept swinging in the wind,

Above the blue snow.

It was beginning winter,

The light moved slowly over the frozen field,

Over the dry seed-crowns,

The beautiful surviving bones

Swinging in the wind.

Light traveled over the wide field;

Stayed.

The weeds stopped swinging.

The mind moved, not alone,

Through the clear air, in the silence.

Was it light?

Was it light within?

Was it light within light?

Stillness becoming alive,

Yet still?

A lively understandable spirit

Once entertained you.

It will come again.

Be still.

Wait.

by Theodore Roethke

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Joseph Epstein at Commentary:

How many times during the past month have you gone to the dictionary, or if not the dictionary then to your computer, to look up a word? I go to mine with some frequency. Here are some of the words within recent weeks I’ve felt the need to look up: “algolagnia,” “orthoepist,” “cromulent,” “himation,” “cosplaying,” and “collocation.” The last word I half-sensed I knew but was less than certain about. I also looked up “despise” and “loath,” to be sure about the difference, if any, between them, and then had to check the difference between the latter when it has an “e” at its end and when it doesn’t. Over the years I must have looked up the word “fiduciary” at least half a dozen times, though I have never used it in print or conversation. I hope to look it up at least six more times before departing the planet. Working with words, it seems, is never done.

How many times during the past month have you gone to the dictionary, or if not the dictionary then to your computer, to look up a word? I go to mine with some frequency. Here are some of the words within recent weeks I’ve felt the need to look up: “algolagnia,” “orthoepist,” “cromulent,” “himation,” “cosplaying,” and “collocation.” The last word I half-sensed I knew but was less than certain about. I also looked up “despise” and “loath,” to be sure about the difference, if any, between them, and then had to check the difference between the latter when it has an “e” at its end and when it doesn’t. Over the years I must have looked up the word “fiduciary” at least half a dozen times, though I have never used it in print or conversation. I hope to look it up at least six more times before departing the planet. Working with words, it seems, is never done.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Steve Newman at Second Thoughts:

Here’s a threshold AI may be approaching: it may soon be the first technology to be more adaptable than we are. It’s not there yet, but you can see it coming – the range of problems to which early adopters are successfully applying AI is simply exploding. Past inventions had limited impact, because they could only be adapted to some uses. But AI may (eventually) adapt itself to any task. When technology makes one job obsolete, people move into another – one that hasn’t been automated yet. But at some point, AI could be retraining faster than people can.

Here’s a threshold AI may be approaching: it may soon be the first technology to be more adaptable than we are. It’s not there yet, but you can see it coming – the range of problems to which early adopters are successfully applying AI is simply exploding. Past inventions had limited impact, because they could only be adapted to some uses. But AI may (eventually) adapt itself to any task. When technology makes one job obsolete, people move into another – one that hasn’t been automated yet. But at some point, AI could be retraining faster than people can.

When that happens, it could well lead to a constellation of technologies powerful enough to usher in the Unrecognizable Age. This constellation would rest on three pillars…

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Alex Abramovich at The New Yorker:

When Willie Nelson performs in and around New York, he parks his bus in Weehawken, New Jersey. While the band sleeps at a hotel in midtown Manhattan, he stays on board, playing dominoes, napping. Nelson keeps musician’s hours. For exercise, he does sit-ups, arm rolls, and leg lifts. He jogs in place. “I’m in pretty good shape, physically, for ninety-two,” he told me recently. “Woke up again this morning, so that’s good.”

When Willie Nelson performs in and around New York, he parks his bus in Weehawken, New Jersey. While the band sleeps at a hotel in midtown Manhattan, he stays on board, playing dominoes, napping. Nelson keeps musician’s hours. For exercise, he does sit-ups, arm rolls, and leg lifts. He jogs in place. “I’m in pretty good shape, physically, for ninety-two,” he told me recently. “Woke up again this morning, so that’s good.”

On September 12th, Nelson drove down to the Freedom Mortgage Pavilion, in Camden. His band, a four-piece, was dressed all in black; Nelson wore black boots, black jeans, and a Bobby Bare T-shirt. His hair, which is thicker and darker than it appears under stage lights, hung in two braids to his waist. A scrim masked the front of the stage, and he walked out unseen, holding a straw cowboy hat. Annie, his wife of thirty-four years, rubbed his back and shoulders. A few friends watched from the wings: members of Sheryl Crow’s band, which had opened for him, and John Doe, the old punk musician, who had flown in from Austin. (At the next show, in Holmdel, Bruce Springsteen showed up.) Out front, big screens played the video for Nelson’s 1986 single “Living in the Promiseland.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Marchese in the New York Times:

The writer, lawyer and human rights activist Raja Shehadeh, who is 74, has spent most of his life living in Ramallah, a city in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. This is where his Palestinian Christian family ended up after fleeing Jaffa, now part of greater Tel Aviv, in 1948, as Jewish paramilitary forces bombed the city. Since he was a much younger man, Shehadeh has been doggedly documenting the experience of living under Israeli occupation — recording what has been lost and what remains.

The writer, lawyer and human rights activist Raja Shehadeh, who is 74, has spent most of his life living in Ramallah, a city in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. This is where his Palestinian Christian family ended up after fleeing Jaffa, now part of greater Tel Aviv, in 1948, as Jewish paramilitary forces bombed the city. Since he was a much younger man, Shehadeh has been doggedly documenting the experience of living under Israeli occupation — recording what has been lost and what remains.

That work, defined by precise description and delicately deployed emotion, has won him widespread acclaim. Shehadeh’s 2007 book, “Palestinian Walks: Forays Into a Vanishing Landscape,” won Britain’s Orwell Prize for political writing. Here in the United States, his book “We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I” was a finalist for the 2023 National Book Award.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Siddhartha Mukherjee in Stat 10:

In oncology we return, again and again, to first principles. The cell is our unit of life and of medicine. When a normal cell becomes malignant, it does not merely divide faster; it eats differently. It hoards glucose, reroutes amino acids, siphons lipids, and improvises when a pathway is blocked. We have learned to poison its DNA, to derail its signaling, to enlist T cells as sentinels. We have been slower to ask a simpler question that sits at the cell’s kitchen table: What if we change what a tumor can eat?

In oncology we return, again and again, to first principles. The cell is our unit of life and of medicine. When a normal cell becomes malignant, it does not merely divide faster; it eats differently. It hoards glucose, reroutes amino acids, siphons lipids, and improvises when a pathway is blocked. We have learned to poison its DNA, to derail its signaling, to enlist T cells as sentinels. We have been slower to ask a simpler question that sits at the cell’s kitchen table: What if we change what a tumor can eat?

For a century, metabolism was oncology’s prologue. In the 1920s, Otto Warburg observed that many cancer cells consume glucose voraciously and convert much of that glucose to lactate even when oxygen is plentiful, a seemingly wasteful choice that became a metabolic signature of malignancy. That insight eventually receded into a footnote while genetics took the stage. But tumors are not static genotypes; they are shape-shifters that adapt to therapy by rewiring their fuel lines.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Philip Clark at the NYRB:

As a teenager, growing up in New Jersey during the 1960s, the pianist Donald Fagen routinely took a bus into Manhattan to hear his jazz heroes in the flesh. The ecstatic improvisational rough-and-tumble of Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, and Willie “The Lion” Smith stayed hardwired inside his brain, and soon Fagen landed at Bard College, where one day in 1967 he overheard a fellow student, Walter Becker from Queens, playing the blues on his guitar in a campus coffee shop. Fagen introduced himself and told Becker how impressed he was by his clean-cut technique. The pair struck up an immediate friendship, then five years later founded Steely Dan, a band that would become one of the defining rock groups of the 1970s.

As a teenager, growing up in New Jersey during the 1960s, the pianist Donald Fagen routinely took a bus into Manhattan to hear his jazz heroes in the flesh. The ecstatic improvisational rough-and-tumble of Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, and Willie “The Lion” Smith stayed hardwired inside his brain, and soon Fagen landed at Bard College, where one day in 1967 he overheard a fellow student, Walter Becker from Queens, playing the blues on his guitar in a campus coffee shop. Fagen introduced himself and told Becker how impressed he was by his clean-cut technique. The pair struck up an immediate friendship, then five years later founded Steely Dan, a band that would become one of the defining rock groups of the 1970s.

In albums like Can’t Buy a Thrill (1972), Pretzel Logic (1974), and Aja (1977), they cultivated a sleek, polished pop that was marinated in jazz, blues, Latin, and rock and roll. Their songs had both a melodic, high-fidelity sheen—a gift to radio airplay—and a level of compositional integrity and instrumental elan that left aficionados agog. Lyrically, they developed a fixation—naysayers considered it an affectation—with pairing waspish observations about social outsiders, the venality of pop culture, and men riding out their midlife crises with relentlessly feel-good music, the harmonies never smudging in sympathy with the deranged words.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

‘Tis the season for overindulgence. But for people with allergies, holiday feasting can be strewn with landmines.

‘Tis the season for overindulgence. But for people with allergies, holiday feasting can be strewn with landmines.

Over three million people worldwide tiptoe around a food allergy. Even more experience watery eyes, runny noses, and uncontrollable sneezing from dust, pollen, or cuddling with a fluffy pet. Over-the-counter medications can control symptoms. But in some people, allergic responses turn deadly.

In anaphylaxis, an overactive immune system releases a flood of inflammatory chemicals that closes up the throat. This chemical storm stresses out the heart and blood vessels and limits oxygen to the brain and other organs. Early diagnosis, especially of shellfish or nut allergies, helps people avoid these foods. And in an emergency, EpiPens loaded with epinephrine can relax airways and save lives. But the pens must be carried at all times, and patients—especially young children—struggle with this.

An alternative is to train the immune system to neutralize its over-zealous response. This month, a team from the University of Toulouse in France presented a long-lasting treatment that fights off anaphylactic shock in mice. Using a vaccine, they rewired part of the immune system to battle Immunoglobulin E (IgE), a protein that’s involved in severe allergic reactions. A single injection into mice launched a tsunami of antibodies against IgE, and levels of those antibodies remained high for at least 12 months—which is over half of a mouse’s life. Despite triggering an immune civil war, the mice’s defenses were still able to fight a parasitic infection. The vaccine is, in theory, a blanket therapy for most food allergies, from peanuts to shellfish.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.