Jack Clark at Import AI:

I walk around the town in which I live and there aren’t drones in the sky or self-driving cars or sidewalk robots or anything like that. And when I spend time on the internet, aimlessly scrolling social media sites in the dead of night as I attempt to extract a burp from my newborn, I might occasionally see some synthetic images or video, but mostly I see what has always been on these feeds: pictures of people I do and don’t know, memes, and a mixture of news and jokes.

I walk around the town in which I live and there aren’t drones in the sky or self-driving cars or sidewalk robots or anything like that. And when I spend time on the internet, aimlessly scrolling social media sites in the dead of night as I attempt to extract a burp from my newborn, I might occasionally see some synthetic images or video, but mostly I see what has always been on these feeds: pictures of people I do and don’t know, memes, and a mixture of news and jokes.

And yet you and I both know there are great changes afoot. Huge new beasts lumbering from some unknown future into our present, dragging with them change.

I saw one of these beasts recently – during a recent moment when the time stars aligned (my wife, toddler, and baby were all asleep at the same time!) I fired up Claude Code with Opus 4.5 and got it to build a predator-prey species simulation with an inbuilt procedural world generator and nice features like A* search for pathfinding – and it one-shot it, producing in about 5 minutes something which I know took me several weeks to build a decade ago when I was teaching myself some basic programming, and which I think would take most seasoned hobbyists several hours. And it did it in minutes.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Back in the early 1930s Gilbert Seldes—a literary critic and early champion of popular culture—was asked to contribute an introduction to a volume of stories by Fitz-James O’Brien, now often regarded as the most original American writer of supernatural fiction between Edgar Allan Poe and Ambrose Bierce. At first Seldes declined, confessing that he’d never read anything by the man. But when the publisher jogged his memory, Seldes remembered that in some anthology or another he had in fact come across “The Diamond Lens,” O’Brien’s 1858 account of an obsessive microscopist who discovers an Eden-like world in a drop of water—and falls in love with the beautiful woman who lives in it.

Back in the early 1930s Gilbert Seldes—a literary critic and early champion of popular culture—was asked to contribute an introduction to a volume of stories by Fitz-James O’Brien, now often regarded as the most original American writer of supernatural fiction between Edgar Allan Poe and Ambrose Bierce. At first Seldes declined, confessing that he’d never read anything by the man. But when the publisher jogged his memory, Seldes remembered that in some anthology or another he had in fact come across “The Diamond Lens,” O’Brien’s 1858 account of an obsessive microscopist who discovers an Eden-like world in a drop of water—and falls in love with the beautiful woman who lives in it. Bardot’s significance was never confined to her acting. She mattered because she altered the image of womanhood at a moment when female beauty was expected to reassure. She unsettled instead. Her looseness, physical and emotional, her apparent boredom with approval, her refusal to perform refinement, all suggested a form of autonomy that was felt before it was articulated. She did not argue for freedom. She behaved as if it already belonged to her.

Bardot’s significance was never confined to her acting. She mattered because she altered the image of womanhood at a moment when female beauty was expected to reassure. She unsettled instead. Her looseness, physical and emotional, her apparent boredom with approval, her refusal to perform refinement, all suggested a form of autonomy that was felt before it was articulated. She did not argue for freedom. She behaved as if it already belonged to her. In April 2025, Donald Trump took the stage to mark the 100th day of his second term as US president. You might have expected a moment of triumph. He had reclaimed the presidency, consolidated power within the Republican Party, and issued a vast range of executive orders. But the mood wasn’t celebratory. It was combative. Trump spent most of his time attacking his predecessor Joe Biden, repeating false claims about the 2020 election, denouncing the press, and warning of threats posed by immigrants, ‘radical Left lunatics’ and corrupt elites. The tone was familiar: angry, aggrieved, unrelenting. Even in victory, the focus was on enemies and retribution.

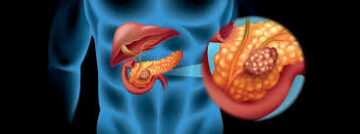

In April 2025, Donald Trump took the stage to mark the 100th day of his second term as US president. You might have expected a moment of triumph. He had reclaimed the presidency, consolidated power within the Republican Party, and issued a vast range of executive orders. But the mood wasn’t celebratory. It was combative. Trump spent most of his time attacking his predecessor Joe Biden, repeating false claims about the 2020 election, denouncing the press, and warning of threats posed by immigrants, ‘radical Left lunatics’ and corrupt elites. The tone was familiar: angry, aggrieved, unrelenting. Even in victory, the focus was on enemies and retribution. A diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is devastating news. Though it makes up only about 3 percent of cancers in the United States, it’s one of the deadliest, and on track for a dark achievement: By 2030, it’s expected to

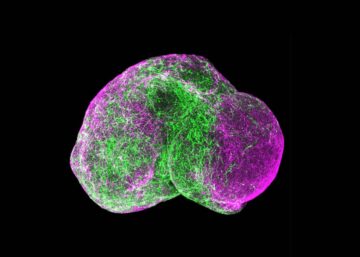

A diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is devastating news. Though it makes up only about 3 percent of cancers in the United States, it’s one of the deadliest, and on track for a dark achievement: By 2030, it’s expected to  When brain organoids were introduced roughly a decade ago, they were a scientific curiosity. The pea-sized blobs of brain tissue grown from stem cells mimicked parts of the human brain, giving researchers a 3D model to study, instead of the usual flat layer of neurons in a dish. Scientists immediately realized they were special. Mini brains developed nearly the whole range of human brain cells, including neurons that sparked with

When brain organoids were introduced roughly a decade ago, they were a scientific curiosity. The pea-sized blobs of brain tissue grown from stem cells mimicked parts of the human brain, giving researchers a 3D model to study, instead of the usual flat layer of neurons in a dish. Scientists immediately realized they were special. Mini brains developed nearly the whole range of human brain cells, including neurons that sparked with  Park Chan-wook is one of Asia’s most famous directors, an auteur beloved as much for his complex, often critical visions of his home country of South Korea as for scenes of stomach-churning horror. But when Park started work on “

Park Chan-wook is one of Asia’s most famous directors, an auteur beloved as much for his complex, often critical visions of his home country of South Korea as for scenes of stomach-churning horror. But when Park started work on “ Kerry James Marshall is contemporary art’s great engine tinkerer. He wants to know how things work. In the 1990s, when his contemporaries were making slight, cerebral works using found objects, photography and minimalism to poeticize the commonplace or reveal hidden ideologies, Marshall fell in love with the creakingly old idea of paintings as “machines.”

Kerry James Marshall is contemporary art’s great engine tinkerer. He wants to know how things work. In the 1990s, when his contemporaries were making slight, cerebral works using found objects, photography and minimalism to poeticize the commonplace or reveal hidden ideologies, Marshall fell in love with the creakingly old idea of paintings as “machines.” EDITOR MAXIM JAKUBOWSKI has recently made something of a specialty of compiling collections of stories inspired by the work of his favorite writers, including Cornell Woolrich and J. G. Ballard. In his newest anthology, he has gathered 24 original (commissioned) stories inspired in one way or another by the life and work of Alfred Hitchcock. Such a collection is no surprise given the ongoing prominence in American film culture of Hitchcock’s work and of Hitchcock as an individual. Indeed, while it has now been a century since the release of the first feature film he directed and nearly half a century since his last, Hitchcock remains one of the most widely recognizable names (and silhouettes) in cinema history. In addition, the concept of the “Hitchcockian” is so well established that it provides a perfect starting point for such a themed collection.

EDITOR MAXIM JAKUBOWSKI has recently made something of a specialty of compiling collections of stories inspired by the work of his favorite writers, including Cornell Woolrich and J. G. Ballard. In his newest anthology, he has gathered 24 original (commissioned) stories inspired in one way or another by the life and work of Alfred Hitchcock. Such a collection is no surprise given the ongoing prominence in American film culture of Hitchcock’s work and of Hitchcock as an individual. Indeed, while it has now been a century since the release of the first feature film he directed and nearly half a century since his last, Hitchcock remains one of the most widely recognizable names (and silhouettes) in cinema history. In addition, the concept of the “Hitchcockian” is so well established that it provides a perfect starting point for such a themed collection. Over the past few months, we’ve seen a surge of skepticism around the phenomenon currently referred to as the “AI boom.” The shift began when OpenAI released GPT-5 this summer

Over the past few months, we’ve seen a surge of skepticism around the phenomenon currently referred to as the “AI boom.” The shift began when OpenAI released GPT-5 this summer  Tragedies, wars, and scandals are transformed into Instagram moments. The instant horror strikes—a terror attack, a catastrophe—social-media platforms erupt with ritual phrases: recycled mantras of “We will take immediate action,” “We condemn…,” “We stand in solidarity….” Rarely do these words lead to deeds. A Ukrainian flag by a profile picture. A #StandWithPalestine sticker. This simplified #empathy and performative #goodness are measured in likes, hearts, and views.

Tragedies, wars, and scandals are transformed into Instagram moments. The instant horror strikes—a terror attack, a catastrophe—social-media platforms erupt with ritual phrases: recycled mantras of “We will take immediate action,” “We condemn…,” “We stand in solidarity….” Rarely do these words lead to deeds. A Ukrainian flag by a profile picture. A #StandWithPalestine sticker. This simplified #empathy and performative #goodness are measured in likes, hearts, and views.