A PUZZLING CONTRAPTION greeted visitors to New York’s Daniel Gallery in 1916: a wooden panel, bearing two bells at its top and a ringer at its base. Framed by painted f-holes, it suggested a musical instrument or a sounding apparatus; a raised handprint at center seemed to indicate its recent use. In fact, the work, appearing with the title Self-Portrait, refused to operate. The disjunction between the abstract composition and the notion of self-portraiture appeared perplexing in its own right; its inoperability only exacerbated the viewer’s frustration and redoubled the artist’s impish provocation.

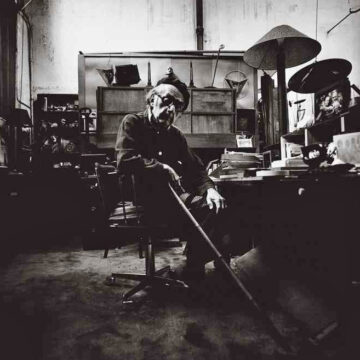

A tiny photograph, currently on view in the Metropolitan Museum’s prodigious Man Ray survey, is all that remains of this since lost work. If its absence speaks obliquely to the Dadaist disregard for aesthetic permanence, its iconography—and its iconoclastic mordancy—echoes throughout his entire corpus. Again and again, we find enigmatic encounters between the mechanical and the erotic; a self-possessed symmetry intermittently upended by formal and conceptual incongruities; disembodied signs and silhouettes in place of integral figurations.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.