Hello Readers and Writers,

We received a large number of submissions of sample essays in our search for new columnists. Most of them were excellent and it was hard deciding whom to accept and whom not to. If you did not get selected, it does not at all mean that we didn’t like what you sent; we just have a limited number of slots and also sometimes we have too many people who want to write about the same subject (for example, a lot of philosophers applied this year). Today we welcome to 3QD the following persons, in alphabetical order by last name:

Abigail Akavia

- Samia Altaf

- Pranab Bardhan

- Jeroen Bouterse

- Nickolas Calabrese

- Niall Chithelen

- Shawn Crawford

- Timothy Don

- Robert Fay

- Joan Harvey

- Mary Hrovat

- Lexi Lerner

- Bill Murray

- Thomas O’Dwyer

- Anitra Pavlico

- Ahmad Saidullah

- Andrea Scrima

- Joseph Shieber

- Tim Sommers

- Adele Stanislaus

- Joshua Wilbur

I will be in touch with all of you in the next days to schedule a start date. The “About Us” page will be updated with short bios and photographs of the new writers no later than the day they start.

Thanks to all of the people who sent samples of writing to us. It was a pleasure to read them all. Congratulations to the new columnists!

Best wishes,

Abbas

Spectator sports can reflect a society’s worst inclinations by promoting pure partisanship.

Spectator sports can reflect a society’s worst inclinations by promoting pure partisanship.

Although some may be heralding the end of free speech, 2018 has been a year of far-reaching debate and discussion. In the coming months, we can anticipate attending or streaming discussions ranging from such topics as the role of race in American politics to the nature of truth, from existential threats posed by artificial intelligence to the value of religion.

Although some may be heralding the end of free speech, 2018 has been a year of far-reaching debate and discussion. In the coming months, we can anticipate attending or streaming discussions ranging from such topics as the role of race in American politics to the nature of truth, from existential threats posed by artificial intelligence to the value of religion. What are you doing? I don’t mean what are you doing with your life, or in general, but what are you doing right now? The answer, in one respect, is simple enough: you’re reading this magazine. Obviously. From a certain economic perspective, however, you’re doing something else, something you don’t realize, something with a sneaky motive that you aren’t admitting to yourself: you are signalling. You are sending signals about the kind of person you are, or want to be. What’s that you say—you’re reading this in the bath, or on your phone in bed, or otherwise in private? Well, the same argument applies. You are acquiring the tools for a “fitness display.” This, the economist Robin Hanson and the writer-programmer Kevin Simler argue in their new book, “

What are you doing? I don’t mean what are you doing with your life, or in general, but what are you doing right now? The answer, in one respect, is simple enough: you’re reading this magazine. Obviously. From a certain economic perspective, however, you’re doing something else, something you don’t realize, something with a sneaky motive that you aren’t admitting to yourself: you are signalling. You are sending signals about the kind of person you are, or want to be. What’s that you say—you’re reading this in the bath, or on your phone in bed, or otherwise in private? Well, the same argument applies. You are acquiring the tools for a “fitness display.” This, the economist Robin Hanson and the writer-programmer Kevin Simler argue in their new book, “ The priest quickly sliced into the captive’s torso and removed his still-beating heart. That sacrifice, one among thousands performed in the sacred city of Tenochtitlan, would feed the gods and ensure the continued existence of the world.

The priest quickly sliced into the captive’s torso and removed his still-beating heart. That sacrifice, one among thousands performed in the sacred city of Tenochtitlan, would feed the gods and ensure the continued existence of the world. Some time back I took a group of students to the Galerie d’Anatomie Comparée at the Jardin des Plantes. This is the famous collection of skeletons laid out according to one version of the order of nature by Georges Cuvier at the turn of the 19th century. We were looking at a display case (added long after Cuvier’s death) that consisted in four rows, one above the other, with five skulls in each row representing five developmental stages of three species of great ape –gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans–, plus Homo sapiens.

Some time back I took a group of students to the Galerie d’Anatomie Comparée at the Jardin des Plantes. This is the famous collection of skeletons laid out according to one version of the order of nature by Georges Cuvier at the turn of the 19th century. We were looking at a display case (added long after Cuvier’s death) that consisted in four rows, one above the other, with five skulls in each row representing five developmental stages of three species of great ape –gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans–, plus Homo sapiens.  In 1765, Russian Empress Catherine the Great heard that the philosopher Dennis Diderot was in dire need of money. As a well-known patron of the arts, sciences, and Enlightenment philosophers, she immediately purchased his entire library. She directed him to keep it at his home and hired him as her librarian with 25 years of salary upfront.

In 1765, Russian Empress Catherine the Great heard that the philosopher Dennis Diderot was in dire need of money. As a well-known patron of the arts, sciences, and Enlightenment philosophers, she immediately purchased his entire library. She directed him to keep it at his home and hired him as her librarian with 25 years of salary upfront. If climate change, nuclear standoffs, Russian trolls, terrorist threats and Donald Trump in the White House don’t cause you feelings of impending doom, you might think about artificial intelligence. I’m not just referring to big-brained robots taking over civilization from us smaller-brained humans, but the more imminent possibility they’ll

If climate change, nuclear standoffs, Russian trolls, terrorist threats and Donald Trump in the White House don’t cause you feelings of impending doom, you might think about artificial intelligence. I’m not just referring to big-brained robots taking over civilization from us smaller-brained humans, but the more imminent possibility they’ll  It’s already happening. Robots and related forms of artificial intelligence are rapidly supplanting what remain of factory workers, call-center operators and clerical staff. Amazon and other online platforms are booting out retail workers. We’ll soon be saying goodbye to truck drivers, warehouse personnel and professionals who do whatever can be replicated, including pharmacists, accountants, attorneys, diagnosticians, translators and financial advisers. Machines may soon do a

It’s already happening. Robots and related forms of artificial intelligence are rapidly supplanting what remain of factory workers, call-center operators and clerical staff. Amazon and other online platforms are booting out retail workers. We’ll soon be saying goodbye to truck drivers, warehouse personnel and professionals who do whatever can be replicated, including pharmacists, accountants, attorneys, diagnosticians, translators and financial advisers. Machines may soon do a  So it is with organising my life. I have tried paper diaries, Google Calendar and to-do apps. No matter the form, what they all have in common is a rigid structure imposed from above. You have a certain number of lines for each day or a finite number of categories into which your plans must fit, or a small palette of colours to highlight or distinguish between events. It drives me insane. So I made my own system: a Google spreadsheet with columns titled “today”, “tomorrow”, “this week”, “weekend”, “this month” and “three months”, and tabs to keep track of expenses, books I’ve read, travel plans, story ideas, and general note-keeping. It’s messy and entirely manual: there are no shortcuts, no functions, no add-ons.

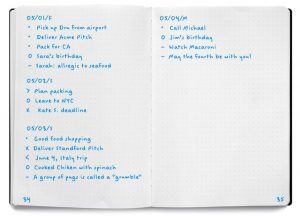

So it is with organising my life. I have tried paper diaries, Google Calendar and to-do apps. No matter the form, what they all have in common is a rigid structure imposed from above. You have a certain number of lines for each day or a finite number of categories into which your plans must fit, or a small palette of colours to highlight or distinguish between events. It drives me insane. So I made my own system: a Google spreadsheet with columns titled “today”, “tomorrow”, “this week”, “weekend”, “this month” and “three months”, and tabs to keep track of expenses, books I’ve read, travel plans, story ideas, and general note-keeping. It’s messy and entirely manual: there are no shortcuts, no functions, no add-ons. Begin, for once, with the ending: the arms at an awful angle, the face blue-lipped above a blot of blood. Only later do we glimpse the woman who corresponds to the corpse. She laughs in a flashback. Or she smiles in the photograph pinned to the board where the police map the murders with thumbtacks, charting tangled speculations with lines of yarn. In light of her death, she comes to life. This is the antiordering typical of the serial killer procedural, a narrative scramble that begins with the answer and ages back toward the question. In the television series Hannibal (NBC, 2013–15), a convicted murderer impales a nurse in prison. He snaps at the officers who come to question him, “I was caught red-handed. There’s no mystery as to who done it. I did it!” Still, the officers insist that they have something to ask.

Begin, for once, with the ending: the arms at an awful angle, the face blue-lipped above a blot of blood. Only later do we glimpse the woman who corresponds to the corpse. She laughs in a flashback. Or she smiles in the photograph pinned to the board where the police map the murders with thumbtacks, charting tangled speculations with lines of yarn. In light of her death, she comes to life. This is the antiordering typical of the serial killer procedural, a narrative scramble that begins with the answer and ages back toward the question. In the television series Hannibal (NBC, 2013–15), a convicted murderer impales a nurse in prison. He snaps at the officers who come to question him, “I was caught red-handed. There’s no mystery as to who done it. I did it!” Still, the officers insist that they have something to ask. For four seasons, Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates has been hosting the genealogy television show Finding Your Roots. In each episode, Mr. Gates presents celebrities with a book full of research into their ancestry, drawing from genealogical records and genetic tests. On a recent show, Mr. Gates introduced the actor Ted Danson to one of his 18th-century ancestors, Oliver Smith of Connecticut. Mr. Danson learned how Mr. Smith defended his seaside town against the British during the Revolutionary War.

For four seasons, Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates has been hosting the genealogy television show Finding Your Roots. In each episode, Mr. Gates presents celebrities with a book full of research into their ancestry, drawing from genealogical records and genetic tests. On a recent show, Mr. Gates introduced the actor Ted Danson to one of his 18th-century ancestors, Oliver Smith of Connecticut. Mr. Danson learned how Mr. Smith defended his seaside town against the British during the Revolutionary War. It isn’t tempting to write about Elon Musk in that it is easy but in that it is an event that few thought we could witness live: a successful businessman letting his true inner recklessness show. All that Musk has done is lose composure – but sadly for him, the window he opened into his mind exposed something unsavoury and disappointing. It is tempting to write about Musk because we can for once stop speculating about how it is that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs cut from the same cloth as Musk and Peter Thiel think, and take a break from amassing piles of secondhand, implicative evidence. Now we have proof – and an opportunity to characterise the psyche of this odiously powerful class of world society.

It isn’t tempting to write about Elon Musk in that it is easy but in that it is an event that few thought we could witness live: a successful businessman letting his true inner recklessness show. All that Musk has done is lose composure – but sadly for him, the window he opened into his mind exposed something unsavoury and disappointing. It is tempting to write about Musk because we can for once stop speculating about how it is that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs cut from the same cloth as Musk and Peter Thiel think, and take a break from amassing piles of secondhand, implicative evidence. Now we have proof – and an opportunity to characterise the psyche of this odiously powerful class of world society. In recent years, Flann O’Brien has often been characterised as the third member of the sacred trinity of Irish modernism, the Holy Ghost to James Joyce’s God the Father and Samuel Beckett’s God the Son. If so, he shares with the Holy Ghost a certain vagueness as to his identity: the press release that accompanies this book refers to him as ‘O’Nolan, or O’Brien, or Myles nagCopaleen or whatever his name may be’. Of these three personas, the first was a civil servant, the second a novelist and the third a satirical columnist for the Irish Times. Although they inhabited the same body, their relations were not always cordial: Flann O’Brien was effectively held hostage by his journalistic rival for two decades between the efflorescence of early novels and his re-emergence with The Hard Life (1961).

In recent years, Flann O’Brien has often been characterised as the third member of the sacred trinity of Irish modernism, the Holy Ghost to James Joyce’s God the Father and Samuel Beckett’s God the Son. If so, he shares with the Holy Ghost a certain vagueness as to his identity: the press release that accompanies this book refers to him as ‘O’Nolan, or O’Brien, or Myles nagCopaleen or whatever his name may be’. Of these three personas, the first was a civil servant, the second a novelist and the third a satirical columnist for the Irish Times. Although they inhabited the same body, their relations were not always cordial: Flann O’Brien was effectively held hostage by his journalistic rival for two decades between the efflorescence of early novels and his re-emergence with The Hard Life (1961).