Boris Dralyuk at The Quarterly Conversation:

If a novel is especially immersive, if the voice of its narrator is sufficiently consistent and evocative, the world it describes may come to life in picturesque color. I say picturesque, rather than vivid, because a novel’s dominant colors may not be entirely lifelike; they may be closer to the rich oils of Rembrandt or the downy pastels of Degas. Such colors suggest life but also remind us of art’s mediating presence. Jacek Dehnel’s lush debut novel, Lala, for instance, is awash in the sepia tones of old photographs, a few of which punctuate the text. Like an old family album, assembled by an eccentric relative with an artistic bent, Dehnel’s work is drawn from life and enriched with intent, with a kind of aesthetic cohesion that bare facts lack.

If a novel is especially immersive, if the voice of its narrator is sufficiently consistent and evocative, the world it describes may come to life in picturesque color. I say picturesque, rather than vivid, because a novel’s dominant colors may not be entirely lifelike; they may be closer to the rich oils of Rembrandt or the downy pastels of Degas. Such colors suggest life but also remind us of art’s mediating presence. Jacek Dehnel’s lush debut novel, Lala, for instance, is awash in the sepia tones of old photographs, a few of which punctuate the text. Like an old family album, assembled by an eccentric relative with an artistic bent, Dehnel’s work is drawn from life and enriched with intent, with a kind of aesthetic cohesion that bare facts lack.

more here.

John Edgar Wideman’s profound new book begins, as it must, with the American Civil War. The first story in this collection, “JB & FD” imagines a kind of conversation between two of the most important figures of that conflict, the white anti-slavery crusader John Brown, hanged in December 1859 for treason, murder, and inciting slave insurrection, and the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had himself been born enslaved.

John Edgar Wideman’s profound new book begins, as it must, with the American Civil War. The first story in this collection, “JB & FD” imagines a kind of conversation between two of the most important figures of that conflict, the white anti-slavery crusader John Brown, hanged in December 1859 for treason, murder, and inciting slave insurrection, and the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had himself been born enslaved. Over this ecstatic high summer, visitors to the Haworth parsonage museum will be able to watch a film that simulates the bird’s-eye view of Emily Brontë’s pet hawk, Nero, as he swoops over the moors to Top Withens, the ruined farmhouse that is the putative model for Wuthering Heights. You’ll be able to listen to the Unthanks, the quavery Northumbrian folk music sisters who have composed music in celebration of Emily’s 200th anniversary. If that’s not enough, you can watch a video installation by Lily Cole, the model-turned-actor-turned-Cambridge-double-first from Devon, which riffs on Heathcliff’s origins as a Liverpool foundling. Finally, Kate Bush, from Kent, has been busy on the moors unveiling a stone. In short, wherever you come from and whoever you are, you will find an

Over this ecstatic high summer, visitors to the Haworth parsonage museum will be able to watch a film that simulates the bird’s-eye view of Emily Brontë’s pet hawk, Nero, as he swoops over the moors to Top Withens, the ruined farmhouse that is the putative model for Wuthering Heights. You’ll be able to listen to the Unthanks, the quavery Northumbrian folk music sisters who have composed music in celebration of Emily’s 200th anniversary. If that’s not enough, you can watch a video installation by Lily Cole, the model-turned-actor-turned-Cambridge-double-first from Devon, which riffs on Heathcliff’s origins as a Liverpool foundling. Finally, Kate Bush, from Kent, has been busy on the moors unveiling a stone. In short, wherever you come from and whoever you are, you will find an  It was barely two hours into Day 1 of AlienCon and 500 years of accepted history and science were already being tossed out. Three thousand people had gathered inside the Civic Auditorium here for a panel discussion featuring presenters from “

It was barely two hours into Day 1 of AlienCon and 500 years of accepted history and science were already being tossed out. Three thousand people had gathered inside the Civic Auditorium here for a panel discussion featuring presenters from “

In 2014, a graduate student at the University of Waterloo, Canada, named

In 2014, a graduate student at the University of Waterloo, Canada, named  Carol Dweck, a psychology professor at Stanford University, remembers asking an undergraduate seminar recently, “How many of you are waiting to find your passion?”

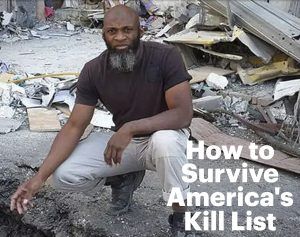

Carol Dweck, a psychology professor at Stanford University, remembers asking an undergraduate seminar recently, “How many of you are waiting to find your passion?” Bilal Abdul Kareem is an expert in staying alive.

Bilal Abdul Kareem is an expert in staying alive.

Amitava Kumar in The Baffler:

Amitava Kumar in The Baffler: Early on in Helen Jukes’s A Honeybee Heart Has Five Openings she ponders the increasing popularity of urban beekeeping, referring to the idea that “one possible psychological response to the apprehension of a threat is to begin producing idealised versions of the thing we perceive of as being at risk”. That’s also a good explanation for the current crop of bee books: not just A Honeybee Heart and Thor Hanson’s Buzz, but Kate Bradbury’s wonderful The Bumblebee Flies Anyway and Maja Lunde’s The History of Bees, among others. Books, like hives, are ways of capturing something and holding on to it: either helping to preserve it, or looking at it closely before it’s gone.

Early on in Helen Jukes’s A Honeybee Heart Has Five Openings she ponders the increasing popularity of urban beekeeping, referring to the idea that “one possible psychological response to the apprehension of a threat is to begin producing idealised versions of the thing we perceive of as being at risk”. That’s also a good explanation for the current crop of bee books: not just A Honeybee Heart and Thor Hanson’s Buzz, but Kate Bradbury’s wonderful The Bumblebee Flies Anyway and Maja Lunde’s The History of Bees, among others. Books, like hives, are ways of capturing something and holding on to it: either helping to preserve it, or looking at it closely before it’s gone. If malignant cells from solid or blood cancers enter the central nervous system (CNS) and grow there, the treatment options and clinical outlook deteriorate rapidly. In a type of leukaemia called acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), invasion of the CNS commonly occurs. To try to limit this, people with the condition often receive radiation or chemotherapy that targets the CNS. If more-effective and less-toxic approaches became available to prevent disease spread to the CNS, this might benefit many people with ALL.

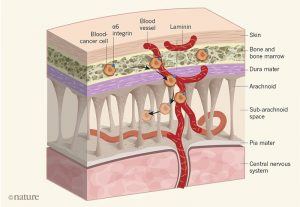

If malignant cells from solid or blood cancers enter the central nervous system (CNS) and grow there, the treatment options and clinical outlook deteriorate rapidly. In a type of leukaemia called acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), invasion of the CNS commonly occurs. To try to limit this, people with the condition often receive radiation or chemotherapy that targets the CNS. If more-effective and less-toxic approaches became available to prevent disease spread to the CNS, this might benefit many people with ALL.  Sheri Berman in The Guardian:

Sheri Berman in The Guardian: In his book The Main Questions of Modern Culture from 1914, the German philosopher Emil Hammacher wrote about the questions of his time—among them the social, woman, and worker questions—their causes, and the longstanding desire to solve them and others, tracing their causes and solution-seeking back to

In his book The Main Questions of Modern Culture from 1914, the German philosopher Emil Hammacher wrote about the questions of his time—among them the social, woman, and worker questions—their causes, and the longstanding desire to solve them and others, tracing their causes and solution-seeking back to  CRISPR has been heralded as one of the

CRISPR has been heralded as one of the  Jamelle Bouie, the chief political correspondent for Slate, recently penned an essay suggesting that the Enlightenment was racist — though the real point seemed to be that liking the Enlightenment too much is kind of racist. Regardless, the essay set off quite a hullabaloo, mostly on Twitter. His main targets were two new books, Enlightenment Now, by Steven Pinker, and Suicide of the West, by yours truly. Jordan Peterson, the controversial Canadian psychologist bogeyman of the moment for many liberals, was namechecked for good measure.

Jamelle Bouie, the chief political correspondent for Slate, recently penned an essay suggesting that the Enlightenment was racist — though the real point seemed to be that liking the Enlightenment too much is kind of racist. Regardless, the essay set off quite a hullabaloo, mostly on Twitter. His main targets were two new books, Enlightenment Now, by Steven Pinker, and Suicide of the West, by yours truly. Jordan Peterson, the controversial Canadian psychologist bogeyman of the moment for many liberals, was namechecked for good measure.