Benedict Carey in The New York Times:

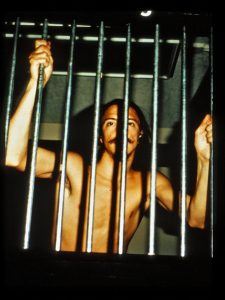

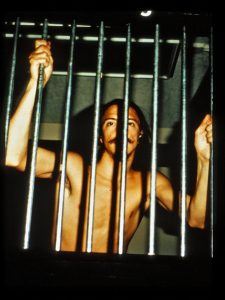

The Stanford prison experiment is a case in point. In the summer of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a midcareer psychologist, recruited 24 college students through newspaper ads and randomly cast half of them as “prisoners” and half as “guards,” setting them up in a mock prison, compete with cells and uniforms. He had the simulation filmed. After six days, Dr. Zimbardo called the experiment off, reporting that the “guards” began to assume their roles too well. They became abusive, some of them shockingly so. Dr. Zimbardo published dispatches about the experiment in a couple of obscure journals. He provided a more complete report in an article he wrote in The New York Times, describing how cruel instincts could emerge spontaneously in ordinary people as a result of situational pressures and expectations. That article and “Quiet Rage,” a documentary about the experiment, helped make Dr. Zimbardo a star in the field and media favorite, most recently in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in the early 2000s.

The Stanford prison experiment is a case in point. In the summer of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a midcareer psychologist, recruited 24 college students through newspaper ads and randomly cast half of them as “prisoners” and half as “guards,” setting them up in a mock prison, compete with cells and uniforms. He had the simulation filmed. After six days, Dr. Zimbardo called the experiment off, reporting that the “guards” began to assume their roles too well. They became abusive, some of them shockingly so. Dr. Zimbardo published dispatches about the experiment in a couple of obscure journals. He provided a more complete report in an article he wrote in The New York Times, describing how cruel instincts could emerge spontaneously in ordinary people as a result of situational pressures and expectations. That article and “Quiet Rage,” a documentary about the experiment, helped make Dr. Zimbardo a star in the field and media favorite, most recently in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in the early 2000s.

Perhaps the central challenge to the study’s claims is that its author coached the “guards” to be hard cases. Is this coaching “not an overt invitation to be abusive in all sorts of psychological ways?” wrote Peter Gray, a psychologist at Boston College who decided to exclude any mention of the simulation from his popular introductory textbook. “And, when the guards did behave in these ways and escalated that behavior, with Zimbardo watching and apparently (by his silence) approving, would that not have confirmed in the subjects’ minds that they were behaving as they should?”

Recent challenges have echoed Dr. Gray’s, and earlier this month Dr. Zimbardo was moved to post a response online.“My instructions to the guards, as documented by recordings of guard orientation, were that they could not hit the prisoners but could create feelings of boredom, frustration, fear and a sense of powerlessness — that is, ‘we have total power of the situation and they have none,’” he wrote. “We did not give any formal or detailed instructions about how to be an effective guard.” In an interview, Dr. Zimbardo said that the simulation was a “demonstration of what could happen” to some people influenced by powerful social roles and outside pressures, and that his critics had missed this point.

Which argument is more persuasive depends to some extent on where you sit and what you may think of Dr. Zimbardo. Is it better to describe his experiment, questions and all — or to ignore it entirely as not real psychology?

More here.

Among Africa’s poorest countries, Togo is surrounded by better-off neighbors that for decades have struggled to defeat lymphatic filariasis, a tropical disease commonly known as elephantiasis (the bacterial infection causes the skin of the swollen areas to resemble that of an elephant’s heavily wrinkled hide). Rising global powers India, Brazil and Indonesia also continue to wage war on an affliction that disables or disfigures 1 in 3 victims. Malaria is the only vector-borne disease that infects more people in the world.

Among Africa’s poorest countries, Togo is surrounded by better-off neighbors that for decades have struggled to defeat lymphatic filariasis, a tropical disease commonly known as elephantiasis (the bacterial infection causes the skin of the swollen areas to resemble that of an elephant’s heavily wrinkled hide). Rising global powers India, Brazil and Indonesia also continue to wage war on an affliction that disables or disfigures 1 in 3 victims. Malaria is the only vector-borne disease that infects more people in the world.

Leave America, and you begin to see it as the rest of the world sees it: as an unpredictable, potentially hostile force dedicated exclusively to protecting its own interests; as a gargantuan military power with an aggressive presence on the world stage and a dangerously undereducated populace. We’ve toppled governments, covertly assassinated democratically elected leaders, waged illegal wars that have poisoned and destabilized entire regions around the globe. The enormous postwar bonus we’ve enjoyed—our status as the world’s darlings—has been eroding steadily away, yet incredibly, we still imagine that everyone loves us. Peering wide-eyed from our self-absorbed bubble, we issue Facebook “apologies” to the rest of the world for our mortifying president and his absurd coterie, not quite realizing that the world, at this point, is less interested in how Americans feel than in foreseeing, assessing, and coping with the damage the United States is likely to wreak on world peace, stability, economic justice, and the environment.

Leave America, and you begin to see it as the rest of the world sees it: as an unpredictable, potentially hostile force dedicated exclusively to protecting its own interests; as a gargantuan military power with an aggressive presence on the world stage and a dangerously undereducated populace. We’ve toppled governments, covertly assassinated democratically elected leaders, waged illegal wars that have poisoned and destabilized entire regions around the globe. The enormous postwar bonus we’ve enjoyed—our status as the world’s darlings—has been eroding steadily away, yet incredibly, we still imagine that everyone loves us. Peering wide-eyed from our self-absorbed bubble, we issue Facebook “apologies” to the rest of the world for our mortifying president and his absurd coterie, not quite realizing that the world, at this point, is less interested in how Americans feel than in foreseeing, assessing, and coping with the damage the United States is likely to wreak on world peace, stability, economic justice, and the environment. The human mind loves nothing more than to build mental boxes — categories — and put things into them, then refuse to accept it when something doesn’t fit. Nowhere is this more clear than in the idea that there are men, and there are women, and that’s it. Alice Dreger is an historian of science, specializing in intersexuality and the relationship between bodies and identities. She is also a successful activist, working to change the way that doctors deal with newborn children who are born intersex. We talk about human sexuality and a number of other hot-button topics, and ruminate on the challenges of being both an intellectual (devoted to truth) and an activist (seeking justice).

The human mind loves nothing more than to build mental boxes — categories — and put things into them, then refuse to accept it when something doesn’t fit. Nowhere is this more clear than in the idea that there are men, and there are women, and that’s it. Alice Dreger is an historian of science, specializing in intersexuality and the relationship between bodies and identities. She is also a successful activist, working to change the way that doctors deal with newborn children who are born intersex. We talk about human sexuality and a number of other hot-button topics, and ruminate on the challenges of being both an intellectual (devoted to truth) and an activist (seeking justice). A

A No matter how much her projects vary in tone, style, and subject matter, Haenel always adjusts the temperature. Languorous and narcotic,

No matter how much her projects vary in tone, style, and subject matter, Haenel always adjusts the temperature. Languorous and narcotic,

In dictatorial states, a failure to applaud the Leader has often been a matter of treason. Last February, following the

In dictatorial states, a failure to applaud the Leader has often been a matter of treason. Last February, following the  While Americans are well-acquainted with Russian online trolls’ 2016 disinformation campaign, there’s a more insidious threat of Russian interference in the coming midterms. The Russians could hack our very election infrastructure, disenfranchising Americans and even altering the vote outcome in key states or districts. Election security experts have warned of it, but state election officials have largely played it down for fear of spooking the public. We still might not know the extent to which state election infrastructure was compromised in 2016, nor how compromised it will be in 2018.

While Americans are well-acquainted with Russian online trolls’ 2016 disinformation campaign, there’s a more insidious threat of Russian interference in the coming midterms. The Russians could hack our very election infrastructure, disenfranchising Americans and even altering the vote outcome in key states or districts. Election security experts have warned of it, but state election officials have largely played it down for fear of spooking the public. We still might not know the extent to which state election infrastructure was compromised in 2016, nor how compromised it will be in 2018. Some environmentalists believe countries should somehow rely on renewables alone to increase their energy supply. Renewables — primarily wind and solar — certainly have a place in the mix, especially locally and at small scale. But because larger-scale renewable sources are dispersed and dilute, they’re limited to favorable conditions, and since they’re intermittent, they require backup energy generation to fill in when the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine.

Some environmentalists believe countries should somehow rely on renewables alone to increase their energy supply. Renewables — primarily wind and solar — certainly have a place in the mix, especially locally and at small scale. But because larger-scale renewable sources are dispersed and dilute, they’re limited to favorable conditions, and since they’re intermittent, they require backup energy generation to fill in when the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine. Why should we mourn the death of a bad person? I was recently struck by an interesting philosophical conversation on death that emerged far outside of the philosophy classroom—on Twitter. Hip-hop fans were grappling with the

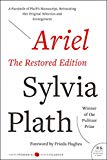

Why should we mourn the death of a bad person? I was recently struck by an interesting philosophical conversation on death that emerged far outside of the philosophy classroom—on Twitter. Hip-hop fans were grappling with the  There’s always been a drumbeat of disapproval of Plath’s work, and it often comes down to: She’s just too much.

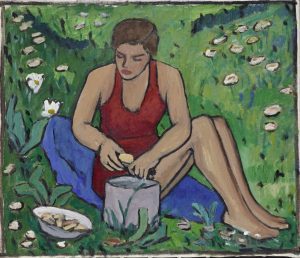

There’s always been a drumbeat of disapproval of Plath’s work, and it often comes down to: She’s just too much.  The idea behind the career-spanning exhibition of Gabriele Münter at the Louisiana is to take a woman who should be one of Germany’s most famous artists and to break her free from Kandinsky—here, she is presented as an artist, separately and simply. Isabelle Jansen, the show’s curator, notes in her recent book on Münter that “through the narrow lens of her relationship with Kandinsky many of her accomplishments have lingered in obscurity.” Jansen hopes to approach “Münter’s oeuvre in all its richness: from classic genres such as portraits and landscapes to interiors, abstractions, and her works of ‘primitivism.’ ”

The idea behind the career-spanning exhibition of Gabriele Münter at the Louisiana is to take a woman who should be one of Germany’s most famous artists and to break her free from Kandinsky—here, she is presented as an artist, separately and simply. Isabelle Jansen, the show’s curator, notes in her recent book on Münter that “through the narrow lens of her relationship with Kandinsky many of her accomplishments have lingered in obscurity.” Jansen hopes to approach “Münter’s oeuvre in all its richness: from classic genres such as portraits and landscapes to interiors, abstractions, and her works of ‘primitivism.’ ” George Orwell conjured up a totalitarian regime where Ignorance Is Strength, but he surely never conceived of this. How can we know that two and two make four, or that the DNC isn’t responsible for its own hacking, or that Vladimir Putin isn’t a bigger American friend than the entire European Union and Nato alliance? As Trump explained so clearly, when he talks about Russia as a rival, he really means it as a compliment, no matter what your lying ears have told you.

George Orwell conjured up a totalitarian regime where Ignorance Is Strength, but he surely never conceived of this. How can we know that two and two make four, or that the DNC isn’t responsible for its own hacking, or that Vladimir Putin isn’t a bigger American friend than the entire European Union and Nato alliance? As Trump explained so clearly, when he talks about Russia as a rival, he really means it as a compliment, no matter what your lying ears have told you. The Stanford prison experiment is a case in point. In the summer of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a midcareer psychologist, recruited 24 college students through newspaper ads and randomly cast half of them as “prisoners” and half as “guards,” setting them up in a mock prison, compete with cells and uniforms. He had the simulation filmed. After six days, Dr. Zimbardo called the experiment off, reporting that the “guards” began to assume their roles too well. They became abusive, some of them shockingly so. Dr. Zimbardo published dispatches about the experiment in a couple of obscure journals. He provided a more complete report in an article he wrote in The New York Times, describing how cruel instincts could emerge spontaneously in ordinary people as a result of situational pressures and expectations. That article and “Quiet Rage,” a documentary about the experiment, helped make Dr. Zimbardo a star in the field and media favorite, most recently in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in the early 2000s.

The Stanford prison experiment is a case in point. In the summer of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a midcareer psychologist, recruited 24 college students through newspaper ads and randomly cast half of them as “prisoners” and half as “guards,” setting them up in a mock prison, compete with cells and uniforms. He had the simulation filmed. After six days, Dr. Zimbardo called the experiment off, reporting that the “guards” began to assume their roles too well. They became abusive, some of them shockingly so. Dr. Zimbardo published dispatches about the experiment in a couple of obscure journals. He provided a more complete report in an article he wrote in The New York Times, describing how cruel instincts could emerge spontaneously in ordinary people as a result of situational pressures and expectations. That article and “Quiet Rage,” a documentary about the experiment, helped make Dr. Zimbardo a star in the field and media favorite, most recently in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal in the early 2000s.