Ta-Nehisi Coates in his blog:

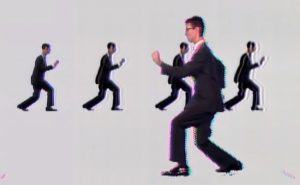

Jackson cranked up “Billie Jean” and I felt it too. For when I saw Michael Jackson glide across the stage that night at Madison Square Garden, mere days before the Twin Towers fell, I did not imagine him so much walking on the moon, as walking on water. And the moonwalk was the least of things. He whipped his mop of hair and, cuffing the mic, stomped with the drums, spun, grabbed the air. I was astounded. There was the matter of his face, which took me back to the self-hatred of the ’80s, but this seemed not to matter because I was watching a miracle—a man had been born to a people who controlled absolutely nothing, and yet had achieved absolute control over the thing that always mattered most—his body.

Jackson cranked up “Billie Jean” and I felt it too. For when I saw Michael Jackson glide across the stage that night at Madison Square Garden, mere days before the Twin Towers fell, I did not imagine him so much walking on the moon, as walking on water. And the moonwalk was the least of things. He whipped his mop of hair and, cuffing the mic, stomped with the drums, spun, grabbed the air. I was astounded. There was the matter of his face, which took me back to the self-hatred of the ’80s, but this seemed not to matter because I was watching a miracle—a man had been born to a people who controlled absolutely nothing, and yet had achieved absolute control over the thing that always mattered most—his body.

And then the song climaxed. He screamed and all the music fell away, save one solitary drum, and boneless Michael seemed to break away, until it was just him and that “Billie Jean” beat, carnal, ancestral. He rolled his shoulders, snaked to the ground, and then backed up, pop-locked, seemed to slow time itself, and I saw him pull away from his body, from the ravished face, which wanted to be white, and all that remained was the soul of him, the gift given onto him, carried in the drum.

I like to think I thought of Zora while watching Jackson. But if not, I am thinking of her now:

It was said, “He will serve us better if we bring him from Africa naked and thing-less.” So the bukra reasoned. They tore away his clothes so that Cuffy might bring nothing away, but Cuffy seized his drum and hid it in his skin under the skull bones. The shin-bones he bore openly, for he thought, “Who shall rob me of shin-bones when they see no drum?” So he laughed with cunning and said, “I, who am borne away, to become an orphan, carry my parents with me. For rhythm is she not my mother, and Drama is her man?” So he groaned aloud in the ships and hid his drum and laughed.

There is no separating the laughter from the groans, the drum from the slave ships, the tearing away of clothes, the being borne away, from the cunning need to hide all that made you human. And this is why the gift of black music, of black art, is unlike any other in America, because it is not simply a matter of singular talent, or even of tradition, or lineage, but of something more grand and monstrous. When Jackson sang and danced, when West samples or rhymes, they are tapping into a power formed under all the killing, all the beatings, all the rape and plunder that made America. The gift can never wholly belong to a singular artist, free of expectation and scrutiny, because the gift is no more solely theirs than the suffering that produced it.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, we will publish at least one post dedicated to Black History Month)

Good questions breathe life into the world. “We Cast a Shadow,” Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s debut novel, asks some of the most important questions fiction can ask, and it does so with energetic and acrobatic prose, hilarious wordplay and great heart.

Good questions breathe life into the world. “We Cast a Shadow,” Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s debut novel, asks some of the most important questions fiction can ask, and it does so with energetic and acrobatic prose, hilarious wordplay and great heart. Einstein’s theory of general relativity is more than a hundred years old, but still it gives physicists headaches. Not only are Einstein’s equations hideously difficult to solve, they also clash with physicists other most-cherish achievement, quantum theory.

Einstein’s theory of general relativity is more than a hundred years old, but still it gives physicists headaches. Not only are Einstein’s equations hideously difficult to solve, they also clash with physicists other most-cherish achievement, quantum theory. These are difficult times for liberal theorists. Fewer than thirty years after the end of the Cold War ushered in a period of unprecedented liberal ascendancy, liberalism today is in retreat—or at least on the defensive—in many parts of the world. A new generation of authoritarian strongmen have come to power in a number of countries, riding waves of populist, nationalist, and anti-globalist sentiment, and other countries may well be headed in the same direction.

These are difficult times for liberal theorists. Fewer than thirty years after the end of the Cold War ushered in a period of unprecedented liberal ascendancy, liberalism today is in retreat—or at least on the defensive—in many parts of the world. A new generation of authoritarian strongmen have come to power in a number of countries, riding waves of populist, nationalist, and anti-globalist sentiment, and other countries may well be headed in the same direction. Education is crucial to a democratic society because it is how we ensure that future citizens will have the knowledge and skills our societies need. In countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and France, some educational institutions play a further role – they educate the elite. All of the current Supreme Court Justices in the US attended either Harvard University or Yale Law School. In the UK, 41 out of 54 of the country’s past prime ministers received their education at the University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge. Seven recent French presidents and 12 prime ministers attended the Paris Institute of Political Studies, commonly called Sciences Po. These universities pride themselves not only in offering superb educational opportunities, but in educating those who will go on to hold influential positions.

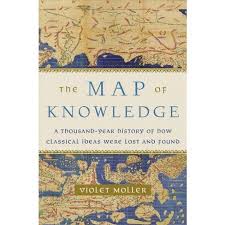

Education is crucial to a democratic society because it is how we ensure that future citizens will have the knowledge and skills our societies need. In countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and France, some educational institutions play a further role – they educate the elite. All of the current Supreme Court Justices in the US attended either Harvard University or Yale Law School. In the UK, 41 out of 54 of the country’s past prime ministers received their education at the University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge. Seven recent French presidents and 12 prime ministers attended the Paris Institute of Political Studies, commonly called Sciences Po. These universities pride themselves not only in offering superb educational opportunities, but in educating those who will go on to hold influential positions. Adelard of Bath would be in demand in the present day. This 12th-century English scholar, arrayed in his striped hat, brilliant green or red cape and lapis lazuli shirt, ‘had a talent’, Violet Moller explains, ‘for communicating complex scientific ideas and adapting them for an amateur, but interested, audience’. Yet he also devoted a good part of his time to profound research, translating mathematical, astronomical and astrological texts from Arabic – astrology being regarded in his time, especially at the Norman court in Sicily, as a very exact science with medical as well as political uses. Adelard knew that court well, but what is particularly interesting is that when he translated Euclid’s Elements into Latin he chose to do it not from its original Greek, the language of nearly half the population of Sicily at that time, but from Arabic, the language of the other half. Nor was he alone in taking such a route: works such as Ptolemy’s Almagest, fundamental for the medieval study of the heavens, seemed to inhabitants of Christian western Europe easier to understand through translation of the Arabic version rather than of the Greek original. The Arabic translators had interspersed their texts with explanations of terms and concepts the meanings of which in the original Greek puzzled western European readers, even if (as was rarely the case) they could understand that language.

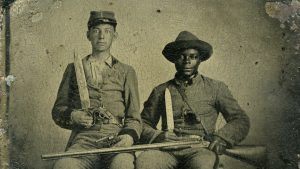

Adelard of Bath would be in demand in the present day. This 12th-century English scholar, arrayed in his striped hat, brilliant green or red cape and lapis lazuli shirt, ‘had a talent’, Violet Moller explains, ‘for communicating complex scientific ideas and adapting them for an amateur, but interested, audience’. Yet he also devoted a good part of his time to profound research, translating mathematical, astronomical and astrological texts from Arabic – astrology being regarded in his time, especially at the Norman court in Sicily, as a very exact science with medical as well as political uses. Adelard knew that court well, but what is particularly interesting is that when he translated Euclid’s Elements into Latin he chose to do it not from its original Greek, the language of nearly half the population of Sicily at that time, but from Arabic, the language of the other half. Nor was he alone in taking such a route: works such as Ptolemy’s Almagest, fundamental for the medieval study of the heavens, seemed to inhabitants of Christian western Europe easier to understand through translation of the Arabic version rather than of the Greek original. The Arabic translators had interspersed their texts with explanations of terms and concepts the meanings of which in the original Greek puzzled western European readers, even if (as was rarely the case) they could understand that language. The yearbook photo that appears on Virginia Governor Ralph Northam’s personal page, featuring a man in blackface and another in a Klan robe, looks to me like a modern update of a familiar image from the Civil War, of a Confederate soldier from the slaveholding class posing with his body servant. The history of the Civil War pairing clarifies the meaning of the Northam scandal. Perhaps the most famous of the soldier-slave photographs depicts Sergeant Andrew Chandler and his uniformed body servant, Silas Chandler. Andrew served in the 44th Mississippi Infantry in the Army of Tennessee from 1861 to 1863. Camp slaves such as Silas were expected to oblige their masters’ every need, including by preparing food, tending to horses, and carrying personal supplies during long marches. Silas likely experienced many of the challenges of military life in camp, on the march, and even, on occasion, the battlefield.

The yearbook photo that appears on Virginia Governor Ralph Northam’s personal page, featuring a man in blackface and another in a Klan robe, looks to me like a modern update of a familiar image from the Civil War, of a Confederate soldier from the slaveholding class posing with his body servant. The history of the Civil War pairing clarifies the meaning of the Northam scandal. Perhaps the most famous of the soldier-slave photographs depicts Sergeant Andrew Chandler and his uniformed body servant, Silas Chandler. Andrew served in the 44th Mississippi Infantry in the Army of Tennessee from 1861 to 1863. Camp slaves such as Silas were expected to oblige their masters’ every need, including by preparing food, tending to horses, and carrying personal supplies during long marches. Silas likely experienced many of the challenges of military life in camp, on the march, and even, on occasion, the battlefield. Born into slavery before the American Revolution,

Born into slavery before the American Revolution,  Few albums of the late 1970s and early 1980s have held up as well as those by Talking Heads, but what to call the music recorded on them? Rock? Pop? New Wave? In the difficulty to pin it down lies its enduring appeal, and that difficulty didn’t come about by accident: impatient with musical categorizations and expectations, frontman David Byrne and the rest of the band kept pushing themselves into new territories even after they’d begun to find success. When they set out to create their fourth album, 1980’s Remain in Light, “they were looking to change the way they made songs.” Instead of leaving the writing to Byrne, “the band wanted a more democratic process. And so they tried something they never had before.”

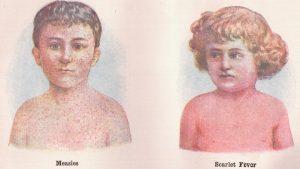

Few albums of the late 1970s and early 1980s have held up as well as those by Talking Heads, but what to call the music recorded on them? Rock? Pop? New Wave? In the difficulty to pin it down lies its enduring appeal, and that difficulty didn’t come about by accident: impatient with musical categorizations and expectations, frontman David Byrne and the rest of the band kept pushing themselves into new territories even after they’d begun to find success. When they set out to create their fourth album, 1980’s Remain in Light, “they were looking to change the way they made songs.” Instead of leaving the writing to Byrne, “the band wanted a more democratic process. And so they tried something they never had before.” Before vaccination became widespread in the 1960s, pediatricians knew to check their patients’ throats for the spray of telltale spots. Scientists raced for decades to develop an effective vaccine. And in the meantime, newspapers printed matter-of-fact

Before vaccination became widespread in the 1960s, pediatricians knew to check their patients’ throats for the spray of telltale spots. Scientists raced for decades to develop an effective vaccine. And in the meantime, newspapers printed matter-of-fact  The Green New Deal has been championed by advocates for getting the United States running on purely renewable energy right away. Some

The Green New Deal has been championed by advocates for getting the United States running on purely renewable energy right away. Some  O

O Mallarmé’s emphasis on the “instantaneous and voluntary” character of Impressionist painting, its “rapid execution,” “effects of simplification,” attraction to “subjects close to home,” its “shifting glimmer of light and shadow,” and notion of “see[ing] … for the first time” corresponds to many contemporary and subsequent accounts of it.

Mallarmé’s emphasis on the “instantaneous and voluntary” character of Impressionist painting, its “rapid execution,” “effects of simplification,” attraction to “subjects close to home,” its “shifting glimmer of light and shadow,” and notion of “see[ing] … for the first time” corresponds to many contemporary and subsequent accounts of it. When composers die prematurely, it’s tempting to imagine what they might have produced had they lived to a riper age. For some musicians, like Mozart or Schubert, the question is moot—each was a mature artist in the full bloom of youth, producing a lifetime’s worth of masterpieces in an astonishingly brief period. But when composers happen to die just when they’re getting started, the question becomes more tantalizing. Consider, for example, the life of Charles Tomlinson Griffes, a man largely—and unjustly—forgotten by the general public today.

When composers die prematurely, it’s tempting to imagine what they might have produced had they lived to a riper age. For some musicians, like Mozart or Schubert, the question is moot—each was a mature artist in the full bloom of youth, producing a lifetime’s worth of masterpieces in an astonishingly brief period. But when composers happen to die just when they’re getting started, the question becomes more tantalizing. Consider, for example, the life of Charles Tomlinson Griffes, a man largely—and unjustly—forgotten by the general public today. Globally, the burden of depression and other mental-health conditions is on the rise. In North America and Europe alone, mental illness accounts for up to 40% of all years lost to disability. And molecular medicine, which has seen huge success in treating diseases such as cancer, has failed to stem the tide. Into that alarming context enters the thought-provoking Good Reasons for Bad Feelings, in which evolutionary psychiatrist Randolph Nesse offers insights that radically reframe psychiatric conditions. In his view, the roots of mental illnesses, such as anxiety and depression, lie in essential functions that evolved as building blocks of adaptive behavioural and cognitive function. Furthermore, like the legs of thoroughbred racehorses — selected for length, but tending towards weakness — some dysfunctional aspects of mental function might have originated with selection for unrelated traits, such as cognitive capacity. Intrinsic vulnerabilities in the human mind could be a trade-off for optimizing unrelated features.

Globally, the burden of depression and other mental-health conditions is on the rise. In North America and Europe alone, mental illness accounts for up to 40% of all years lost to disability. And molecular medicine, which has seen huge success in treating diseases such as cancer, has failed to stem the tide. Into that alarming context enters the thought-provoking Good Reasons for Bad Feelings, in which evolutionary psychiatrist Randolph Nesse offers insights that radically reframe psychiatric conditions. In his view, the roots of mental illnesses, such as anxiety and depression, lie in essential functions that evolved as building blocks of adaptive behavioural and cognitive function. Furthermore, like the legs of thoroughbred racehorses — selected for length, but tending towards weakness — some dysfunctional aspects of mental function might have originated with selection for unrelated traits, such as cognitive capacity. Intrinsic vulnerabilities in the human mind could be a trade-off for optimizing unrelated features. t is time to shift the geography of political tribalism in order to recognize the United States as a tribal society. This was the essence of the keynote speech given by Kwame Anthony Appiah at “

t is time to shift the geography of political tribalism in order to recognize the United States as a tribal society. This was the essence of the keynote speech given by Kwame Anthony Appiah at “