Category: Recommended Reading

Sanford Sylvan (1953 – 2019)

Is Anti-Intellectualism Ever Good for Democracy?

Adam Waters and EJ Dionne, Jr. in Dissent:

Donald Trump campaigned for the presidency and continues to govern as a man who is anti-intellectual, as well as anti-fact and anti-truth. “The experts are terrible,” Trump said while discussing foreign policy during the 2016 campaign. “Look at the mess we’re in with all these experts that we have.” But Trump belongs to a long U.S. tradition of skepticism about the role and motivations of intellectuals in political life. And his particularly toxic version of this tradition raises provocative and difficult questions: Are there occasions when anti-intellectualism is defensible or justified? Should we always dismiss charges that intellectuals are out of touch or too protective of established ways of thinking? In 1963 the historian Richard Hofstadter published Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, in which he traced a recurring mode of thought prevalent, as he saw it, in U.S. religion, business, education, and politics. “There has always been in our national experience a type of mind which elevates hatred to a kind of creed,” he wrote. “[F]or this mind, group hatreds take a place in politics similar to the class struggle in some other modern societies.” On the list of widely hated groups were Masons, abolitionists, Catholics, Mormons, Jews, black Americans, immigrants, international bankers—and intellectuals.

Donald Trump campaigned for the presidency and continues to govern as a man who is anti-intellectual, as well as anti-fact and anti-truth. “The experts are terrible,” Trump said while discussing foreign policy during the 2016 campaign. “Look at the mess we’re in with all these experts that we have.” But Trump belongs to a long U.S. tradition of skepticism about the role and motivations of intellectuals in political life. And his particularly toxic version of this tradition raises provocative and difficult questions: Are there occasions when anti-intellectualism is defensible or justified? Should we always dismiss charges that intellectuals are out of touch or too protective of established ways of thinking? In 1963 the historian Richard Hofstadter published Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, in which he traced a recurring mode of thought prevalent, as he saw it, in U.S. religion, business, education, and politics. “There has always been in our national experience a type of mind which elevates hatred to a kind of creed,” he wrote. “[F]or this mind, group hatreds take a place in politics similar to the class struggle in some other modern societies.” On the list of widely hated groups were Masons, abolitionists, Catholics, Mormons, Jews, black Americans, immigrants, international bankers—and intellectuals.

Hofstadter’s skepticism of mass opinion—on both the left and the right—came through quite clearly. “[T]he heartland of America,” he wrote, “filled with people who are often fundamentalist in religion, nativist in prejudice, isolationist in foreign policy, and conservative in economics, has constantly rumbled with an underground revolt against all these tormenting manifestations of our modern predicament.” It is not an accident that these words sound familiar in the Trump era. A liberalism that viewed the heartland with skepticism was bound to encourage the heartland to return the favor.

More here.

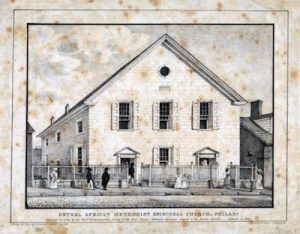

African America’s First Protest Meeting

William L. Katz in BlackPast.Org:

In January 1817 nearly 3,000 African American men met at the Bethel A.M.E. Church (popularly known as Mother Bethel AME) in Philadelphia and denounced the American Colonization Society’s plan to resettle free blacks in West Africa. This gathering was the first black mass protest meeting in the United States. The black leaders who summoned the men to the church endorsed the ACS scheme and fully expected the black men who gathered there to follow their leadership. Instead they rejected the scheme and forced the black leaders to embrace their position.

In January 1817 nearly 3,000 African American men met at the Bethel A.M.E. Church (popularly known as Mother Bethel AME) in Philadelphia and denounced the American Colonization Society’s plan to resettle free blacks in West Africa. This gathering was the first black mass protest meeting in the United States. The black leaders who summoned the men to the church endorsed the ACS scheme and fully expected the black men who gathered there to follow their leadership. Instead they rejected the scheme and forced the black leaders to embrace their position.

The genesis of this remarkable meeting can found in the early efforts of Captain Paul Cuffee, a wealthy black New Bedford ship owner. After an 1811 visit to the British colony of Sierra Leone which had been established to receive free blacks and later recaptives — blacks freed by the British Navy from slaving vessels taking them from Africa to the New World — Cuffee envisioned a similar colony for African Americans somewhere in West Africa. To promote his vision, Cuffee, at great financial loss, brought 38 black volunteer settlers from the United States to Sierra Leone in 1815.

When he returned to the United States with news of the resettlement he persuaded many of the most influential black leaders of the era to support him in transporting larger numbers of African Americans to a yet to be determined colony on the West African coast. Rev. Peter Williams of New York, Rev. Daniel Coker in Baltimore, and James Forten, Bishop Richard Allen, and Rev. Absalom Jones all of Philadelphia, who were the most important African American leaders in the United States at that time, enthusiastically endorsed the plan.

Given the dire situation faced by free blacks in the North during that era, their endorsement was understandable. The vote was denied to all but a handful of black men. No black women could vote at the time. Black workers were limited in the occupations they could pursue and the wages they could receive. In Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and other Northern cities they were subject to attack by white mobs and to the ever present threat of slavecatchers who kidnapped fugitive slaves and on occasion those who had never been enslaved. Thus to many leaders in the “free” North colonization seemed an attractive option.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, we will publish at least one post dedicated to Black History Month)

Saturday, February 9, 2019

A special class of vivid, textural words defy linguistic theory: could ‘ideophones’ unlock the secrets of humans’ first utterances?

David Robson in Aeon:

If you don’t speak Japanese but would like, momentarily, to feel like a linguistic genius, take a look at the following words. Try to guess their meaning from the two available options:

If you don’t speak Japanese but would like, momentarily, to feel like a linguistic genius, take a look at the following words. Try to guess their meaning from the two available options:

1. nurunuru (a) dry or (b) slimy?

2. pikapika (a) bright or (b) dark?

3. wakuwaku (a) excited or (b) bored?

4. iraira (a) happy or (b) angry?

5. guzuguzu (a) moving quickly or (b) moving slowly?

6. kurukuru (a) spinning around or (b) moving up and down?

7. kosokoso (a) walking quietly or (b) walking loudly?

8. gochagocha (a) tidy or (b) messy?

9. garagara (a) crowded or (b) empty?

10. tsurutsuru (a) smooth or (b) rough?

The answers are: 1(b); 2(a); 3(a); 4(b); 5(b); 6(a); 7(a); 8(b); 9(b) 10(a).

If you think this exercise is futile, you’re in tune with traditional linguistic thinking. One of the founding axioms of linguistic theory, articulated by Ferdinand de Saussure in the early 19th century, is that any particular linguistic sign – a sound, a mark on the page, a gesture – is arbitrary, and dictated solely by social convention. Save those rare exceptions such as onomatopoeias, where a word mimics a noise – eg, ‘cuckoo’, ‘achoo’ or ‘cock-a-doodle-doo’ – there should be no inherent link between the way a word sounds and the concept it represents; unless we have been socialised to think so, nurunuru shouldn’t feel more ‘slimy’ any more than it feels ‘dry’.

Yet many world languages contain a separate set of words that defies this principle. Known as ideophones, they are considered to be especially vivid and evocative of sensual experiences.

More here.

The 500-Year-Long Science Experiment

Sarah Zhang in The Atlantic:

In the year 2514, some future scientist will arrive at the University of Edinburgh (assuming the university still exists), open a wooden box (assuming the box has not been lost), and break apart a set of glass vials in order to grow the 500-year-old dried bacteria inside. This all assumes the entire experiment has not been forgotten, the instructions have not been garbled, and science—or some version of it—still exists in 2514.

By then, the scientists who dreamed up this 500-year experiment—Charles Cockell at the University of Edinburgh and his German and U.S. collaborators—will be long dead. They’ll never know the answers to the questions that intrigued them back in 2014, about the longevity of bacteria. Cockell had once forgotten about a dried petri dish of Chroococcidiopsis for 10 years, only to find the cells were still viable. Scientists have revived bacteria from 118-year-old cans of meat and, more controversially, from amber and salt crystals millions of years old.

All this suggests, according to Ralf Möller, a microbiologist at the German Aerospace Center and collaborator on the experiment, that “life on our planet is not limited by human standards.” Understanding what that means requires work that goes well beyond the human life span.

More here.

Twelve Scholars Respond to the APA’s Guidance for Treating Men and Boys

From Quillette:

Introduction — John P. Wright, Ph.D.

Introduction — John P. Wright, Ph.D.

Thirteen years in the making, the American Psychological Association (APA) released the newly drafted “Guidelines for Psychological Practice for Boys and Men.” Backed by 40 years of science, the APA claims, the guidelines boldly pronounce that “traditional masculinity” is the cause and consequence of men’s mental health concerns. Masculine stoicism, the APA tells us, prevents men from seeking treatment when in need, while beliefs rooted in “masculine ideology” perpetuate men’s worst behaviors—including sexual harassment and rape. Masculine ideology, itself a byproduct of the “patriarchy,” benefits men and simultaneously victimizes them, the guidelines explain. Thus, the APA committee advises therapists that men need to become allies to feminism. “Change men,” an author of the report stated, “and we can change the world.”

But if the reaction to the APA’s guidelines is any indication, this change won’t happen anytime soon. Criticism was immediate and fierce. Few outside of a handful of departments within the academy had ever heard of “masculine ideology,” and fewer still understood how defining traditional masculinity by men’s most boorish—even criminal—behavior would serve the interests of men or entice them to seek professional help.

More here.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan – Allah Hoo

They Really Don’t Make Music Like They Used To

Greg Milner in the New York Times:

I’m talking about loudness as a measure of sound within a particular recording. Our ears perceive loudness in an environment by reflexively noting the dynamic range — the difference between the softest and loudest sounds (in this case, the environment is the recording itself, not the room you are playing it in). A blaring television commercial may make us turn down the volume of our sets, but its sonic peaks are no higher than the regular programming preceding it. The commercial just hits those peaks more often. A radio station playing classical music may be broadcasting a signal with the same maximum strength as one playing hip-hop, but the classical station broadcast will hit that peak perhaps once every few minutes, while the hip-hop station’s signal may peak several times per second.

I’m talking about loudness as a measure of sound within a particular recording. Our ears perceive loudness in an environment by reflexively noting the dynamic range — the difference between the softest and loudest sounds (in this case, the environment is the recording itself, not the room you are playing it in). A blaring television commercial may make us turn down the volume of our sets, but its sonic peaks are no higher than the regular programming preceding it. The commercial just hits those peaks more often. A radio station playing classical music may be broadcasting a signal with the same maximum strength as one playing hip-hop, but the classical station broadcast will hit that peak perhaps once every few minutes, while the hip-hop station’s signal may peak several times per second.

A loud environment in this sense is one with a limited dynamic range — highs that peak very high, and lows that aren’t much lower. For decades, musicians and engineers have employed dynamic range compression to make recordings sound fuller. Compression boosts the quieter parts and tamps down louder ones to create a narrower range. Historically, compression was usually applied during the mastering stage, the final steps through which a finished recording becomes a commercial release.

More here.

Saturday Poem

nextdoor app

a young man desperately buries himself under damp leaves while helicopters hunt him police laugh as he tries to hide in the foliage a neighbor with a device to eavesdrop on scanners catches this tidbit shares it with the online group crime doesn’t pay lol you think the leaves make you invisible haha meanwhile he lies on his back on the wet grass of a stranger’s yard weaving a fast and futile dwelling from the earth what does it feel like to be held this way by the whole world pressing your back dew slicking your eyebrows thinking of your mother who is putting your baby girl to sleep your second grade teacher who framed your first poem your fourth grade teacher who told you you won’t be shit your sister who followed you from room to room wanting you to play with her your two cousins shot in the same week one in the pupil another in the lung and for a moment you nearly weep but no you lie perfectly still directly in the white beam of light rivulets running from magnolia leaves down your temples into the soil.

by Shabnam Piryaei

from Split This Rock

Reading

Khaled Khalifa’s ‘Death Is Hard Work’

David L Ulin at the LA Times:

“If you really want to erase or distort a story,” Khaled Khalifa declares in his astonishing new novel “Death Is Hard Work,” “you should turn it into several different stories with different endings and plenty of incidental details.” He’s referring to the salutary comforts of narrative. This — or so we like to reassure ourselves — is one reason we turn to literature: as a balm, an expression of the bonds that bring us together, rather than the divisions that tear us apart.

“If you really want to erase or distort a story,” Khaled Khalifa declares in his astonishing new novel “Death Is Hard Work,” “you should turn it into several different stories with different endings and plenty of incidental details.” He’s referring to the salutary comforts of narrative. This — or so we like to reassure ourselves — is one reason we turn to literature: as a balm, an expression of the bonds that bring us together, rather than the divisions that tear us apart.

And yet, what happens when that literature takes place in a landscape where such attachments have been severed, where “[r]ites and rituals meant nothing now”? These concerns are central to “Death Is Hard Work,” which takes place in contemporary Syria and involves the efforts of three adult children to transport the body of their father, Abdel Latif al-Salim, from Damascus, where he has died, for burial in his home village of Anabiya, a drive that would normally take just a handful of hours.

more here.

Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist

Helen Hackett at Literary Review:

According to Elizabeth Goldring in this engrossing biography, the earliest recorded use of the term ‘miniature’ in English literature comes in Sir Philip Sidney’s prose romance The New Arcadia, written in the early 1580s. Four ladies bathe and splash playfully in the River Ladon, personified as male, and he responds delightedly by making numerous bubbles, as if ‘he would in each of those bubbles set forth the miniature of them’. It’s a pleasing image, calling to mind the delicacy and radiance of the works of Nicholas Hilliard, the leading miniaturist (or ‘limner’) of the Elizabethan age, whom Sidney knew and with whom he discussed emerging ideas about the theory and practice of art. In some ways, a miniature had the ephemerality of a bubble, capturing an individual at a fleeting moment in time, often recorded in an inscription noting the date and the sitter’s age. Yet it also made that moment last for posterity, as shown in this sumptuous book, where Hilliard’s subjects gaze back at us piercingly from many of the 250 colour illustrations.

According to Elizabeth Goldring in this engrossing biography, the earliest recorded use of the term ‘miniature’ in English literature comes in Sir Philip Sidney’s prose romance The New Arcadia, written in the early 1580s. Four ladies bathe and splash playfully in the River Ladon, personified as male, and he responds delightedly by making numerous bubbles, as if ‘he would in each of those bubbles set forth the miniature of them’. It’s a pleasing image, calling to mind the delicacy and radiance of the works of Nicholas Hilliard, the leading miniaturist (or ‘limner’) of the Elizabethan age, whom Sidney knew and with whom he discussed emerging ideas about the theory and practice of art. In some ways, a miniature had the ephemerality of a bubble, capturing an individual at a fleeting moment in time, often recorded in an inscription noting the date and the sitter’s age. Yet it also made that moment last for posterity, as shown in this sumptuous book, where Hilliard’s subjects gaze back at us piercingly from many of the 250 colour illustrations.

more here.

A Dying Young Woman Reminds Us How to Live

Lori Gottlieb in The New York Times:

When we meet Julie Yip-Williams at the beginning of “The Unwinding of the Miracle,” her eloquent, gutting and at times disarmingly funny memoir, she has already died, having succumbed to colon cancer in March 2018 at the age of 42, leaving behind her husband and two young daughters. And so she joins the recent spate of debuts from dead authors, including Paul Kalanithi and Nina Riggs, who also documented their early demises. We might be tempted to assume that these books were written mostly for the writers themselves, as a way to make sense of a frightening diagnosis and uncertain future; or for their families, as a legacy of sorts, in order to be known more fully while alive and kept in mind once they were gone.

When we meet Julie Yip-Williams at the beginning of “The Unwinding of the Miracle,” her eloquent, gutting and at times disarmingly funny memoir, she has already died, having succumbed to colon cancer in March 2018 at the age of 42, leaving behind her husband and two young daughters. And so she joins the recent spate of debuts from dead authors, including Paul Kalanithi and Nina Riggs, who also documented their early demises. We might be tempted to assume that these books were written mostly for the writers themselves, as a way to make sense of a frightening diagnosis and uncertain future; or for their families, as a legacy of sorts, in order to be known more fully while alive and kept in mind once they were gone.

By dint of being published, though, they were also written for us — strangers looking in from the outside. From our seemingly safe vantage point, we’re granted the privilege of witnessing a life-altering experience while knowing that we have the luxury of time. We can set the book down and mindlessly scroll through Twitter, defer our dreams for another year or worry about repairing a rift later, because our paths are different. Except that’s not entirely true. Life has a 100 percent mortality rate; each of us will die, and most of us have no idea when. Therefore, Yip-Williams tells us, she has set out to write an “exhortation” to us in our complacency: “Live while you’re living, friends.”

More here.

Mouth Full of Blood

RO Kwon in The Guardian:

A writer’s life and work are not a gift to mankind; they are its necessity,” says Toni Morrison in “Peril”, the brief, remarkable introduction to her newest book. In this collection by the Nobel prize winning author – widely, ardently considered to be one of the world’s best writers – there are 40 years of her essays, speeches and meditations, including her thoughts and arguments about politics, art and writing. The book contains exhortations and transcribed question-and-answer sessions, reflections and analyses, exegeses and commencement talks. In other words, it’s a large, rich, heterogeneous book, and hallelujah.

A writer’s life and work are not a gift to mankind; they are its necessity,” says Toni Morrison in “Peril”, the brief, remarkable introduction to her newest book. In this collection by the Nobel prize winning author – widely, ardently considered to be one of the world’s best writers – there are 40 years of her essays, speeches and meditations, including her thoughts and arguments about politics, art and writing. The book contains exhortations and transcribed question-and-answer sessions, reflections and analyses, exegeses and commencement talks. In other words, it’s a large, rich, heterogeneous book, and hallelujah.

Organised into three parts titled “The Foreigner’s Home”, “Black Matter(s)”, and “God’s Language”, each section begins with a moving address to the dead: respectively, to those who died on September 11, Martin Luther King and James Baldwin. “The Foreigner’s Home” is centred on politics, particularly on questions of otherness, foreignness, citizenship and nationalism. Of who, especially in the US, gets to belong. Morrison makes plain that racism, tribalism and bigotry are nothing new – are, in fact, inherent to the broken foundation on which the nation was formed.

Friday, February 8, 2019

The only way to end the class divide: the case for abolishing private schools

Melissa Benn in The Guardian (about six months ago):

Unlikely as it might sound, one of the most electric political meetings I have ever attended was a lecture on the Finnish educational system given by Pasi Sahlberg, the Finnish educator and author, in London in the spring of 2012. Sahlberg, who was speaking to a packed committee room 14 of the House of Commons – the most magnificent of a run of grand meeting rooms that directly overlook the Thames – has a rather laconic manner of delivery. However, in this particular instance, his flat speaking style proved the perfect vehicle for an unexpectedly radical message.

Unlikely as it might sound, one of the most electric political meetings I have ever attended was a lecture on the Finnish educational system given by Pasi Sahlberg, the Finnish educator and author, in London in the spring of 2012. Sahlberg, who was speaking to a packed committee room 14 of the House of Commons – the most magnificent of a run of grand meeting rooms that directly overlook the Thames – has a rather laconic manner of delivery. However, in this particular instance, his flat speaking style proved the perfect vehicle for an unexpectedly radical message.

Sahlberg described how Finnish education had evolved, in the postwar period, from a steeply hierarchical one, rather like our own, made up of private, selective and less-well regarded “local” schools, to become a system in which every child attends the “common school”. The long march to educational reform was partly initiated to strengthen the Finnish nation after the second world war, and to defend it against Russian incursions in particular.

Finland’s politicians and educational figures recognised that a profoundly unequal education system did not simply reproduce inequality down the generations, but weakened the fabric of the nation itself. Following a long period of discussion – which drew in figures from the political right and left, educators and academics – Finland abolished its fee-paying schools and instituted a nationwide comprehensive system from the early 1970s onwards. Not only did such reforms lead to the closing of the attainment gap between the richest and poorest students, it also turned Finland into one of the global educational success stories of the modern era.

More here.

The Magic of Denis Johnson

J. Robert Lennon at The Nation:

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden takes its title from an opening suite of 10 anecdotes, each narrated by the same advertising executive: a wry, observant man gently dissatisfied with his work and primarily concerned, in these pages, with the inexplicable lives of those around him. In one story, he rather jarringly refers to a group of disabled adults as “cinema zombies, but good zombies, zombies with minds and souls,” and we realize that this is how he sees all people, himself included—stumbling travelers, puzzled by life. He introduces us to a woman challenged to kiss an amputee’s stump, and tells the story of a sexual proposition passed under a men’s-room door; a memorial service produces an unexpected artifact, and a valuable painting is thrown into a fire.

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden takes its title from an opening suite of 10 anecdotes, each narrated by the same advertising executive: a wry, observant man gently dissatisfied with his work and primarily concerned, in these pages, with the inexplicable lives of those around him. In one story, he rather jarringly refers to a group of disabled adults as “cinema zombies, but good zombies, zombies with minds and souls,” and we realize that this is how he sees all people, himself included—stumbling travelers, puzzled by life. He introduces us to a woman challenged to kiss an amputee’s stump, and tells the story of a sexual proposition passed under a men’s-room door; a memorial service produces an unexpected artifact, and a valuable painting is thrown into a fire.

Characters act in “Largesse” with evident conviction, but they don’t understand why; others may or may not be who they say they are. “His breast-tag said ‘Ted,’ ” the adman says of a stranger at a gathering, “but he introduced himself as someone else.” A phone call from a dying ex-wife results in an emotional apology… but which ex-wife was it, the one named Ginny, or the one named Jenny?

more here.

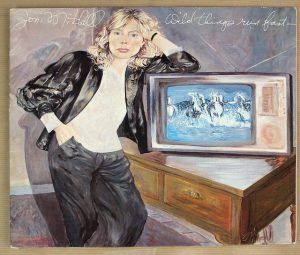

Travels with Joni Mitchell

Amit Chaudhuri at n+1:

AROUND 2014, I began to talk to friends about Joni and was disappointed—surprised—by how little they knew. These were people who listened to music. I had a conversation about her with a highly accomplished ex-student in New York, a writer who had musical training, who thought I was talking about Janis Joplin. This was related to a problem: the plethora of Js among women musicians of the time, which led to their conflation into a genre. Janis Joplin, Judy Collins, Joan Baez, and Joni Mitchell: the last three especially were seen as interchangeable. Even if I put down my ex-student’s confusion to uncharacteristic generational ignorance, I found that, on mentioning Joni to a contemporary I had to work hard to distinguish her from Joan Baez. My friend had dismissed—not in the sense of “rejected,” but “taxonomized”—Joni as being part of a miscellany of singers with long, straight hair, high, clear voices, and a sincerity that shone brightly in the mass protests of the late ’60s. Visually, in her early acoustic performances with guitar, and even in her singing, she appropriated the folk singer’s persona to the point of parody, while the songwriting was absolutely unexpected. To prove this to my friend, I played her “Rainy Night House” and “Chinese Café / Unchained Melody.” It became clear in twenty seconds that Mitchell was not Joan Baez.

AROUND 2014, I began to talk to friends about Joni and was disappointed—surprised—by how little they knew. These were people who listened to music. I had a conversation about her with a highly accomplished ex-student in New York, a writer who had musical training, who thought I was talking about Janis Joplin. This was related to a problem: the plethora of Js among women musicians of the time, which led to their conflation into a genre. Janis Joplin, Judy Collins, Joan Baez, and Joni Mitchell: the last three especially were seen as interchangeable. Even if I put down my ex-student’s confusion to uncharacteristic generational ignorance, I found that, on mentioning Joni to a contemporary I had to work hard to distinguish her from Joan Baez. My friend had dismissed—not in the sense of “rejected,” but “taxonomized”—Joni as being part of a miscellany of singers with long, straight hair, high, clear voices, and a sincerity that shone brightly in the mass protests of the late ’60s. Visually, in her early acoustic performances with guitar, and even in her singing, she appropriated the folk singer’s persona to the point of parody, while the songwriting was absolutely unexpected. To prove this to my friend, I played her “Rainy Night House” and “Chinese Café / Unchained Melody.” It became clear in twenty seconds that Mitchell was not Joan Baez.

more here.

Does the United States need a religious left?

Nadia Marzouki in The Immanent Frame:

Amid the global rise of the Christian right, some intellectuals and politicians have emphasized the need to affirm a stronger religious left in the United States. The Democrats’ downfall in 2016, this argument goes, has shown the limits of ideological platforms that ignore matters of faith and belonging and stick to technocratic and secular jargon. From this perspective, in order to win the culture war against right-wing evangelicals, progressives urgently need to include religion in their strategy.

Amid the global rise of the Christian right, some intellectuals and politicians have emphasized the need to affirm a stronger religious left in the United States. The Democrats’ downfall in 2016, this argument goes, has shown the limits of ideological platforms that ignore matters of faith and belonging and stick to technocratic and secular jargon. From this perspective, in order to win the culture war against right-wing evangelicals, progressives urgently need to include religion in their strategy.

Since 2016, various attempts have been made at mobilizing religious progressives against the religious right. Vote Common Good, a group of progressive Christians, has worked toward bringing evangelicals closer to the Democratic Party. Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) insistently speaks about his faith and how it inspires his political project. Journalist Jack Jenkins has suggested that Booker could be “a candidate for the ‘religious left.’” It has become quite trendy to blame Democrats and the liberal left for neglecting the importance of religion for the people, and to encourage progressives to try and emulate the political methods of right-wing populists and the religious right.

Such sudden injunctions to mobilize religion for political gains ignore the fact that progressive and radical religious movements have been a key part of social and political activism throughout American history—from the Social Gospel movement to the civil rights movements, to activists inspired by liberation theology, to Catholic Nuns today advocating for equal access to health care. More specifically, the now fashionable call to speak or act religious for political gains poses at least three problems.

More here.

The Lutheran Pastor Calling for a Sexual Reformation

Eliza Griswold at The New Yorker:

Bolz-Weber had flown in from her home in Denver to promote her book “Shameless,” which was published last week. In it, she calls for a sexual reformation within Christianity, modelled on the arguments of Martin Luther, the theologian who launched the Protestant Reformation by nailing ninety-five theses to a church door in Wittenberg, Germany, in the sixteenth century. (One of the slogans of the church that Bolz-Weber founded in Denver, House for All Sinners and Saints, is “Nailing shit to the church door since 1517.”) Luther rebelled against the legalism that pervaded the Church during the Middle Ages, arguing that the focus on sinful conduct was unnecessary, because people were already redeemed through Christ’s sacrifice. “Luther saw the harm that the teachings of the Church were doing in the lives of those in his care,” Bolz-Weber told me. “He decided to be less loyal to the teachings than to their well-being.” For all of his faults—among them, rabid anti-Semitism—Luther’s theology centered around real life. “He talked about farting and drinking and he was kind of like Nadia,” the bishop Jim Gonia, who heads the Rocky Mountain Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, told me. Gonia summed up Luther’s idea like this: “Now that we don’t need to worry that we’re good enough for God, how do we direct our attention to our neighbor?”

Bolz-Weber had flown in from her home in Denver to promote her book “Shameless,” which was published last week. In it, she calls for a sexual reformation within Christianity, modelled on the arguments of Martin Luther, the theologian who launched the Protestant Reformation by nailing ninety-five theses to a church door in Wittenberg, Germany, in the sixteenth century. (One of the slogans of the church that Bolz-Weber founded in Denver, House for All Sinners and Saints, is “Nailing shit to the church door since 1517.”) Luther rebelled against the legalism that pervaded the Church during the Middle Ages, arguing that the focus on sinful conduct was unnecessary, because people were already redeemed through Christ’s sacrifice. “Luther saw the harm that the teachings of the Church were doing in the lives of those in his care,” Bolz-Weber told me. “He decided to be less loyal to the teachings than to their well-being.” For all of his faults—among them, rabid anti-Semitism—Luther’s theology centered around real life. “He talked about farting and drinking and he was kind of like Nadia,” the bishop Jim Gonia, who heads the Rocky Mountain Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, told me. Gonia summed up Luther’s idea like this: “Now that we don’t need to worry that we’re good enough for God, how do we direct our attention to our neighbor?”

more here.

When Jamaica Led the Postcolonial Fight Against Exploitation

Adom Getachew in the Boston Review:

In 1972 the socialist left swept to power in Jamaica. Calling for the strengthening of workers’ rights, the nationalization of industries, and the expansion of the island’s welfare state, the People’s National Party (PNP), led by the charismatic Michael Manley, sought nothing less than to overturn the old order under which Jamaicans had long labored—first as enslaved, then indentured, then colonized, and only recently as politically free of Great Britain. Jamaica is a small island, but the ambition of the project was global in scale.

In 1972 the socialist left swept to power in Jamaica. Calling for the strengthening of workers’ rights, the nationalization of industries, and the expansion of the island’s welfare state, the People’s National Party (PNP), led by the charismatic Michael Manley, sought nothing less than to overturn the old order under which Jamaicans had long labored—first as enslaved, then indentured, then colonized, and only recently as politically free of Great Britain. Jamaica is a small island, but the ambition of the project was global in scale.

Two years before his election as prime minister, Manley took to the pages of Foreign Affairs to situate his democratic socialism within a novel account of international relations. While the largely North Atlantic readers of the magazine might have identified the fissures of the Cold War as the dominant conflict of their time, Manley argued otherwise. The “real battleground,” he declared, was located “in that largely tropical territory which was first the object of colonial exploitation, second, the focus of non-Caucasian nationalism and more latterly known as the underdeveloped and the developing world as it sought euphemisms for its condition.” Manley displaced the Cold War’s East–West divide, instead drawing on a longstanding anti-colonial critique to look at the world along its North–South axis. When viewed from the “tropics,” the world was not bifurcated by ideology, but by a global economy whose origins lay in the project of European imperial expansion.

More here.