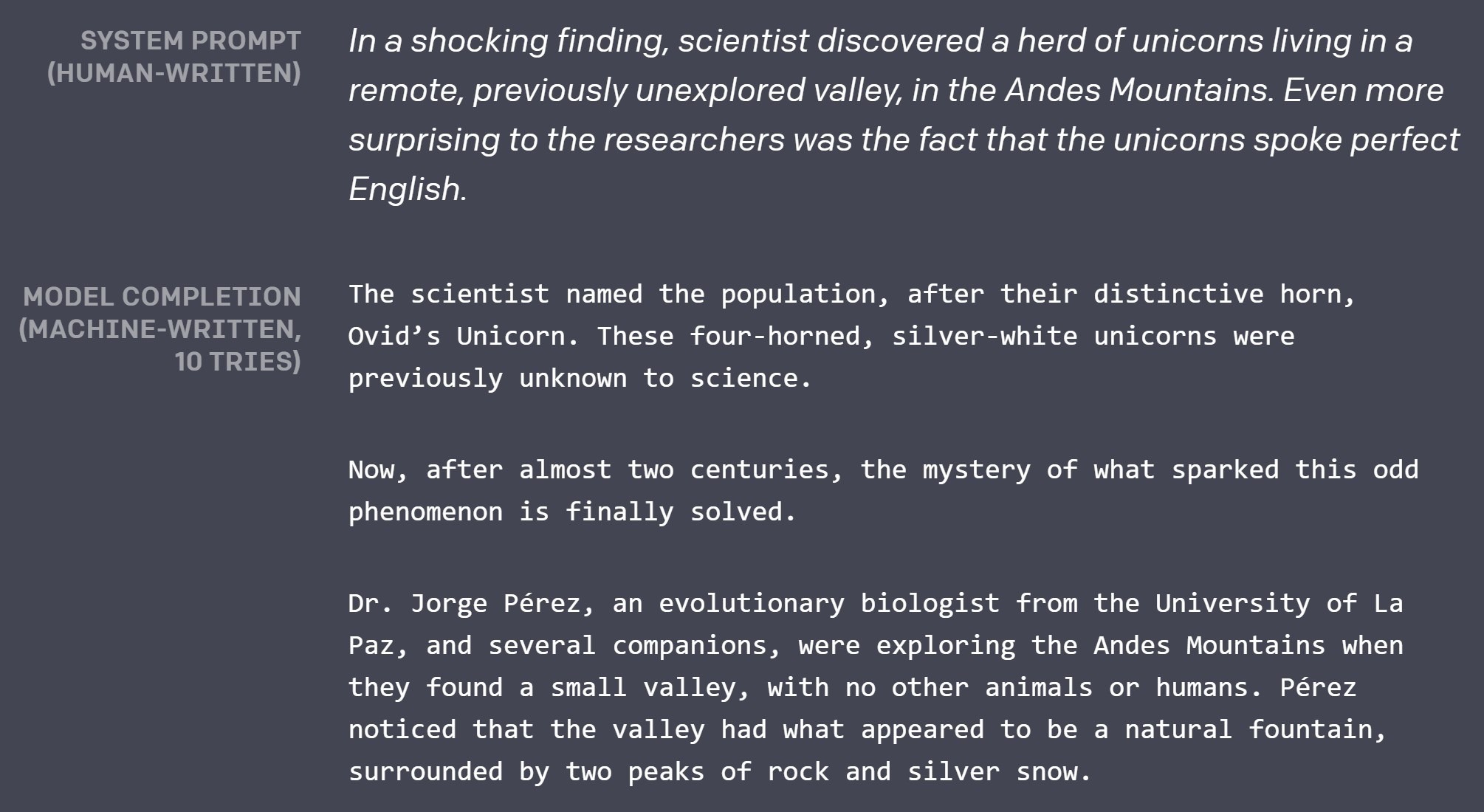

From BlackPast.Org:

On December 10, 1963, while still the leading spokesman for the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X gave a speech at a rally in Detroit, Michigan. That speech outlined his basic black nationalist philosophy and established him as a major critic of the civil rights movement. The speech appears below.

And during the few moments that we have left, we want to have just an off-the-cuff chat between you and me — us. We want to talk right down to earth in a language that everybody here can easily understand. We all agree tonight, all of the speakers have agreed, that America has a very serious problem. Not only does America have a very serious problem, but our people have a very serious problem. America’s problem is us. We’re her problem. The only reason she has a problem is she doesn’t want us here. And every time you look at yourself, be you black, brown, red, or yellow — a so-called Negro — you represent a person who poses such a serious problem for America because you’re not wanted. Once you face this as a fact, then you can start plotting a course that will make you appear intelligent, instead of unintelligent.

And during the few moments that we have left, we want to have just an off-the-cuff chat between you and me — us. We want to talk right down to earth in a language that everybody here can easily understand. We all agree tonight, all of the speakers have agreed, that America has a very serious problem. Not only does America have a very serious problem, but our people have a very serious problem. America’s problem is us. We’re her problem. The only reason she has a problem is she doesn’t want us here. And every time you look at yourself, be you black, brown, red, or yellow — a so-called Negro — you represent a person who poses such a serious problem for America because you’re not wanted. Once you face this as a fact, then you can start plotting a course that will make you appear intelligent, instead of unintelligent.

What you and I need to do is learn to forget our differences. When we come together, we don’t come together as Baptists or Methodists. You don’t catch hell ’cause you’re a Baptist, and you don’t catch hell ’cause you’re a Methodist. You don’t catch hell ’cause you’re a Methodist or Baptist. You don’t catch hell because you’re a Democrat or a Republican. You don’t catch hell because you’re a Mason or an Elk. And you sure don’t catch hell ’cause you’re an American; ’cause if you was an American, you wouldn’t catch no hell. You catch hell ’cause you’re a black man. You catch hell, all of us catch hell, for the same reason.

So we are all black people, so-called Negroes, second-class citizens, ex-slaves. You are nothing but a ex-slave. You don’t like to be told that. But what else are you? You are ex-slaves. You didn’t come here on the “Mayflower.” You came here on a slave ship — in chains, like a horse, or a cow, or a chicken. And you were brought here by the people who came here on the “Mayflower.” You were brought here by the so-called Pilgrims, or Founding Fathers. They were the ones who brought you here.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, we will publish at least one post dedicated to Black History Month)

As a teenager in Maryland in the 1950s, Mary Allen Wilkes had no plans to become a software pioneer — she dreamed of being a litigator. One day in junior high in 1950, though, her geography teacher surprised her with a comment: “Mary Allen, when you grow up, you should be a computer programmer!” Wilkes had no idea what a programmer was; she wasn’t even sure what a computer was. Relatively few Americans were. The first digital computers had been built barely a decade earlier at universities and in government labs.

As a teenager in Maryland in the 1950s, Mary Allen Wilkes had no plans to become a software pioneer — she dreamed of being a litigator. One day in junior high in 1950, though, her geography teacher surprised her with a comment: “Mary Allen, when you grow up, you should be a computer programmer!” Wilkes had no idea what a programmer was; she wasn’t even sure what a computer was. Relatively few Americans were. The first digital computers had been built barely a decade earlier at universities and in government labs. In keeping with a mathematical concept known as the pigeonhole principle, roosting pigeons have to cram together if there are more pigeons than spots available, with some birds sharing holes. But

In keeping with a mathematical concept known as the pigeonhole principle, roosting pigeons have to cram together if there are more pigeons than spots available, with some birds sharing holes. But  How would you describe 2018?

How would you describe 2018? NOW THAT SHE IS NO LONGER

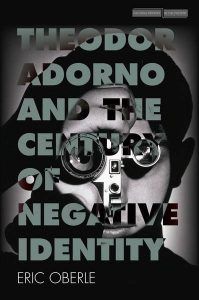

NOW THAT SHE IS NO LONGER  The history of the Frankfurt School in America is usually told as a story of one-way traffic. The question being: What did America get from the Frankfurt School? The answer usually offered: a lot! We got Marcuse, Neumann, Lowenthal, Fromm, and, for a time, Horkheimer and Adorno (who ultimately went back to Germany after the war)—the whole array of émigré culture that helped transform the United States from a provincial outpost of arts and letters into a polyglot Parnassus of the world.

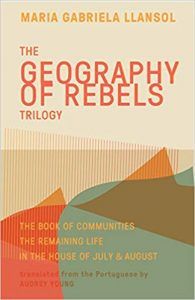

The history of the Frankfurt School in America is usually told as a story of one-way traffic. The question being: What did America get from the Frankfurt School? The answer usually offered: a lot! We got Marcuse, Neumann, Lowenthal, Fromm, and, for a time, Horkheimer and Adorno (who ultimately went back to Germany after the war)—the whole array of émigré culture that helped transform the United States from a provincial outpost of arts and letters into a polyglot Parnassus of the world. Imagine if Don Mclean’s song American Pie was written about Christian mysticism instead of rock-n-roll. That’s my elevator pitch/description of the Portuguese writer, Maria Gabriela Llansol’s, English language debut: The Geography of Rebels Trilogy. Originally published as three separate books—The Book of Communities, The Remaining Life, and In the House of July and August—it has been painstakingly translated by Audrey Young and released by the Texas indie publisher Deep Vellum in a single volume.

Imagine if Don Mclean’s song American Pie was written about Christian mysticism instead of rock-n-roll. That’s my elevator pitch/description of the Portuguese writer, Maria Gabriela Llansol’s, English language debut: The Geography of Rebels Trilogy. Originally published as three separate books—The Book of Communities, The Remaining Life, and In the House of July and August—it has been painstakingly translated by Audrey Young and released by the Texas indie publisher Deep Vellum in a single volume. Skipping along those tones mentally and emotionally, we’ve left the world of biography, in fact, and we enter the universe of pure metaphor. Growing up and as an artist, Baldwin had a great interest in masks, specifically the masks of blackness and maleness, the various roles we appropriate or condemn the better to define ourselves. In one of his last pieces of writing, he talked about the various projections that Michael Jackson, for instance, had to withstand and survive if he did not internalize what America deemed ugly, which is to say his blackness and his maleness. In Anthony Barboza’s extraordinary image from 1980, we have Jackson’s real pre–Michael Jackson face, the face God made for him and he did not make for himself. His internal life disfigured his body and his face in order to find some approximation of it in front of the camera and in front of the world, and it’s such a gift to have Barboza’s portrait before those decisions were made, and to see his extraordinary vulnerability and the beauty of his real face.

Skipping along those tones mentally and emotionally, we’ve left the world of biography, in fact, and we enter the universe of pure metaphor. Growing up and as an artist, Baldwin had a great interest in masks, specifically the masks of blackness and maleness, the various roles we appropriate or condemn the better to define ourselves. In one of his last pieces of writing, he talked about the various projections that Michael Jackson, for instance, had to withstand and survive if he did not internalize what America deemed ugly, which is to say his blackness and his maleness. In Anthony Barboza’s extraordinary image from 1980, we have Jackson’s real pre–Michael Jackson face, the face God made for him and he did not make for himself. His internal life disfigured his body and his face in order to find some approximation of it in front of the camera and in front of the world, and it’s such a gift to have Barboza’s portrait before those decisions were made, and to see his extraordinary vulnerability and the beauty of his real face. Here I put forward my own unabashedly partisan view of philosophy, cribbed from Plato’s cave: philosophy does not put sight into blind eyes; rather, it turns the soul around to face the light. A soul will not turn except under painful exposure to all the questions it forgot to ask, and it will quickly turn back again unless it is pressured to acknowledge the meaninglessness of a life in which it does not continue to ask them. Philosophy doesn’t jazz up the life you were living—it snatches that life out of your grip. It doesn’t make you feel smarter, it makes you feel stupider: doing philosophy, you discover you don’t even know the most basic things.

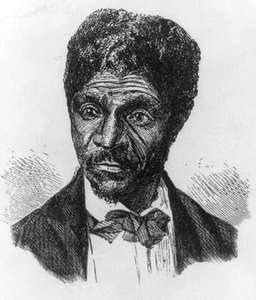

Here I put forward my own unabashedly partisan view of philosophy, cribbed from Plato’s cave: philosophy does not put sight into blind eyes; rather, it turns the soul around to face the light. A soul will not turn except under painful exposure to all the questions it forgot to ask, and it will quickly turn back again unless it is pressured to acknowledge the meaninglessness of a life in which it does not continue to ask them. Philosophy doesn’t jazz up the life you were living—it snatches that life out of your grip. It doesn’t make you feel smarter, it makes you feel stupider: doing philosophy, you discover you don’t even know the most basic things. On March 6, 1857, the U.S.

On March 6, 1857, the U.S.  Dan Mallory, a book editor turned novelist, is tall, good-looking, and clever. His novel, “

Dan Mallory, a book editor turned novelist, is tall, good-looking, and clever. His novel, “ “We’re the United States’ only proverb laboratory. Our mission is to stress-test the nation’s proverbs. To provide rigorous backing for the good ones, and weed out the bad ones.”

“We’re the United States’ only proverb laboratory. Our mission is to stress-test the nation’s proverbs. To provide rigorous backing for the good ones, and weed out the bad ones.” THIS SHOW’S TITLE comes from a letter that my grandmother wrote to me around ten years ago. I had just begun collecting stories from my family and had asked her to describe the house she lived in as a young girl in the Philippines. She drafted a long, detailed letter, filled with drawings. But she forgot to specify my apartment number on the address, so the letter was eventually returned to her. When she re-sent it, she added a note, lamenting, “All the while I thought you had received this.”

THIS SHOW’S TITLE comes from a letter that my grandmother wrote to me around ten years ago. I had just begun collecting stories from my family and had asked her to describe the house she lived in as a young girl in the Philippines. She drafted a long, detailed letter, filled with drawings. But she forgot to specify my apartment number on the address, so the letter was eventually returned to her. When she re-sent it, she added a note, lamenting, “All the while I thought you had received this.” In contrast to her opponents, Murdoch stresses the reality of moral life. To acknowledge the reality of moral life is to recognize that the world contains such things as kindness, as foolishness, as mean-spiritedness. These are genuine features of reality, and someone who comes to know that some course of action would be foolish comes to know something about how things are in the world. This view is sometimes thought to be ruled out by a certain scientistic conception of the natural, one that restricts what exists to the things that feature in our best scientific theories. Such a view is too restricted, Murdoch thinks, to capture the reality of our lives – including our lives as moral agents. Goodness is sovereign, which is to say a real, if transcendent, aspect of the world.

In contrast to her opponents, Murdoch stresses the reality of moral life. To acknowledge the reality of moral life is to recognize that the world contains such things as kindness, as foolishness, as mean-spiritedness. These are genuine features of reality, and someone who comes to know that some course of action would be foolish comes to know something about how things are in the world. This view is sometimes thought to be ruled out by a certain scientistic conception of the natural, one that restricts what exists to the things that feature in our best scientific theories. Such a view is too restricted, Murdoch thinks, to capture the reality of our lives – including our lives as moral agents. Goodness is sovereign, which is to say a real, if transcendent, aspect of the world. The rumors spread like wildfire: Muslims were secretly lacing a Sri Lankan village’s food with sterilization drugs. Soon, a video circulated that appeared to show a Muslim shopkeeper admitting to drugging his customers — he had misunderstood the question that was angrily put to him. Then all hell broke loose. Over a several-day span, dozens of mosques and Muslim-owned shops and homes were burned down across multiple towns. In one home, a young journalist was trapped, and perished.

The rumors spread like wildfire: Muslims were secretly lacing a Sri Lankan village’s food with sterilization drugs. Soon, a video circulated that appeared to show a Muslim shopkeeper admitting to drugging his customers — he had misunderstood the question that was angrily put to him. Then all hell broke loose. Over a several-day span, dozens of mosques and Muslim-owned shops and homes were burned down across multiple towns. In one home, a young journalist was trapped, and perished.