Garrett Felber in Boston Review:

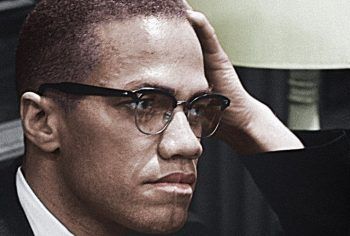

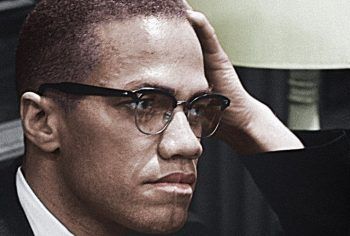

More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us in these pageson the fiftieth anniversary of King’s death this year, “There are costs to canonization.” The primary vehicle of canonization in Malcolm’s case has been The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which has been translated into thirty languages and has been widely read—by students and activists alike—across the United States and abroad.

More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us in these pageson the fiftieth anniversary of King’s death this year, “There are costs to canonization.” The primary vehicle of canonization in Malcolm’s case has been The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which has been translated into thirty languages and has been widely read—by students and activists alike—across the United States and abroad.

…There have long been rumors of three missing chapters among scholars; some think Haley cut them from the book following Malcolm’s assassination because their politics diverged or the book had transformed during his tumultuous last year. Whatever the reasoning, “The Negro” is a fragment of the book Malcolm intended to publish—a book that would be virtually unrecognizable to readers of his autobiography today. We will never fully know that book, of course, but “The Negro” chapter forces us, finally, to engage with it.

…In “The Negro,” he called Democrats and Republicans “labels that mean nothing” to black people. Elsewhere he noted how in the United Nations, there are those who vote yes, those who vote no, and those who abstain. And those who abstain often “have just as much weight.” A sign of political maturity, he believed, was to first register black people, then organize them, and vote only when a candidate represented their interests.

This analysis culminated in one of Malcolm’s most famous addresses, “The Ballot or the Bullet.” Delivered in April 1964 shortly after breaking with the Nation of Islam and forming his independent organization Muslim Mosque, Inc., Malcolm told a Cleveland audience, “A ballot is like a bullet. You don’t throw your ballots until you see a target, and if that target is not within your reach, keep your ballot in your pocket.” Many historians have seen the speech as Malcolm’s first ideological break from the Nation of Islam, an index of his developing political thought. “The Negro,” by contrast, shows this thought as an extension of the Nation of Islam’s political development rather than a departure. Even the title of his speech may have been borrowed from the pages of Muhammad Speaks; in 1962, a front-page story about the struggle in Fayette County, Tennessee, to register black voters was subtitled: “Fayette Fought For Freedom With Bullets and Ballots.”

More here. (Note: Throughout February, we will publish at least one post dedicated to Black History Month)

The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope—scheduled to come online in the early 2020s—will use a 3.2-gigapixel camera to photograph a giant swath of the heavens. It’ll keep it up for 10 years, every night with a clear sky, creating the world’s largest astronomical stop-motion movie.

The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope—scheduled to come online in the early 2020s—will use a 3.2-gigapixel camera to photograph a giant swath of the heavens. It’ll keep it up for 10 years, every night with a clear sky, creating the world’s largest astronomical stop-motion movie.

Reclaiming national sovereignty has been a mantra of Brexiteers. Yet one of the many ironies of Brexit is that Britain actually enjoys a special status within the EU. In fact, the many exemptions and concessions secured by the UK – from constraints on sovereignty imposed by EU membership – brings to mind Carl Schmitt’s

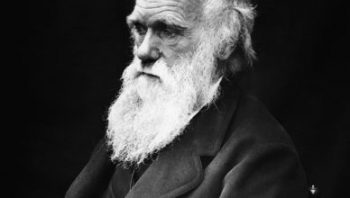

Reclaiming national sovereignty has been a mantra of Brexiteers. Yet one of the many ironies of Brexit is that Britain actually enjoys a special status within the EU. In fact, the many exemptions and concessions secured by the UK – from constraints on sovereignty imposed by EU membership – brings to mind Carl Schmitt’s  Darwin is recognized as a great scientist, but he was also a profound, and sometimes poetic, writer. His style of striking images, suggestive metaphors, and apt concision becomes apparent in Gregory Brown’s Missa Charles Darwin, which sets Darwin’s words to sacred music. Brown’s “Missa” (Latin for mass) adapts the genre of sacred music and liturgy to give expression to some of Darwin’s most important ideas – which are also the most theologically disturbing ones. The result is a strangely beautiful piece of music, made even more intriguing by

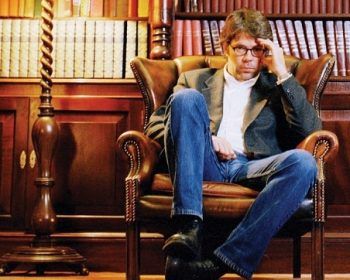

Darwin is recognized as a great scientist, but he was also a profound, and sometimes poetic, writer. His style of striking images, suggestive metaphors, and apt concision becomes apparent in Gregory Brown’s Missa Charles Darwin, which sets Darwin’s words to sacred music. Brown’s “Missa” (Latin for mass) adapts the genre of sacred music and liturgy to give expression to some of Darwin’s most important ideas – which are also the most theologically disturbing ones. The result is a strangely beautiful piece of music, made even more intriguing by  But in fact what is remarkable about the opprobrium heaped on Franzen by the online literati is that it seems to have very little to do with his actual work. The author of the Medium essay I quoted above clearly has not read Franzen’s fiction (or if she has she has failed to understand it). But she knows how she feels about the man. And this is typical. Successive waves of online Franzen-hatred have generally taken the form of ad hominem responses to essays, or to remarks made in interviews, or to his occasional appearances on television. That Franzen’s opinions – expressed in forms, very much including the essay, that he has not mastered and that tend to serve him poorly – so often go against the contemporary grain (for instance his distrust of social media) or situate him squarely in a trainspotterish cul de sac of hobbyism (all that birdwatching) mean that he is, from the point of view of the virtue-signalling culture warriors of Twitter, a soft target. Here, once again, Franzen may have to take some of the blame. It’s difficult to think of another contemporary novelist who is served so poorly by out-of-context quotation, or by his own inability to craft acceptable soundbites.

But in fact what is remarkable about the opprobrium heaped on Franzen by the online literati is that it seems to have very little to do with his actual work. The author of the Medium essay I quoted above clearly has not read Franzen’s fiction (or if she has she has failed to understand it). But she knows how she feels about the man. And this is typical. Successive waves of online Franzen-hatred have generally taken the form of ad hominem responses to essays, or to remarks made in interviews, or to his occasional appearances on television. That Franzen’s opinions – expressed in forms, very much including the essay, that he has not mastered and that tend to serve him poorly – so often go against the contemporary grain (for instance his distrust of social media) or situate him squarely in a trainspotterish cul de sac of hobbyism (all that birdwatching) mean that he is, from the point of view of the virtue-signalling culture warriors of Twitter, a soft target. Here, once again, Franzen may have to take some of the blame. It’s difficult to think of another contemporary novelist who is served so poorly by out-of-context quotation, or by his own inability to craft acceptable soundbites. Although he admired Marxist historical materialism and applied a version of it to his study of the past in his work, the roots of Hobsbawm’s attachment to communism were emotional rather than theoretical. As Richard Evans writes, ‘The ecstatic feeling of being part of a great mass movement whose members were closely bound together by their common ideals engendered a lifelong, viscerally emotional sense of belonging.’ Early in his life, Evans tells us, Hobsbawm experienced a similar emotion in the boy scouts. His need to belong may have reflected his insecure family life (he became an orphan at the age of fourteen when his mother died of tuberculosis). He remained a member of the British Communist Party until shortly before its dissolution in 1991. But British communism was more like a marginal sect than a mass movement, and he seems to have felt a certain distance from its activists, never becoming one himself.

Although he admired Marxist historical materialism and applied a version of it to his study of the past in his work, the roots of Hobsbawm’s attachment to communism were emotional rather than theoretical. As Richard Evans writes, ‘The ecstatic feeling of being part of a great mass movement whose members were closely bound together by their common ideals engendered a lifelong, viscerally emotional sense of belonging.’ Early in his life, Evans tells us, Hobsbawm experienced a similar emotion in the boy scouts. His need to belong may have reflected his insecure family life (he became an orphan at the age of fourteen when his mother died of tuberculosis). He remained a member of the British Communist Party until shortly before its dissolution in 1991. But British communism was more like a marginal sect than a mass movement, and he seems to have felt a certain distance from its activists, never becoming one himself. Today James Baldwin is most frequently encountered as a

Today James Baldwin is most frequently encountered as a  Relics have the power to galvanize and unify people for diverse ideological ends. A broad category of objects, relics can be anything from the body parts of holy figures to objects intimately associated with their lives. They have long been central to many religions, prized for their ability to transmit the aura and sanctity of those to whom they belonged. Relics of Saint Teresa of Avila were so valued, for example, that when her body was exhumed for canonization in 1622, clerics smuggled away her fingers and toes, sometimes in their mouths. But there are secular relics as well, from clippings of Marie Antoinette’s hair to the preserved corpse of Vladimir Lenin. Through sheer proximity to these relics, the faithful feel the full solemnity of the deceased’s presence and their greater impact on history.

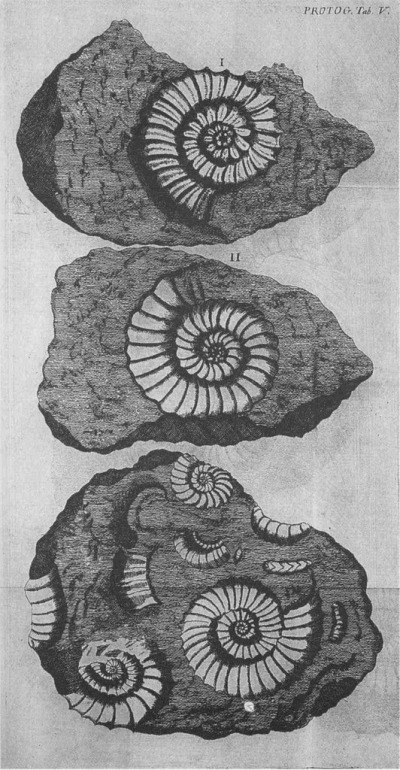

Relics have the power to galvanize and unify people for diverse ideological ends. A broad category of objects, relics can be anything from the body parts of holy figures to objects intimately associated with their lives. They have long been central to many religions, prized for their ability to transmit the aura and sanctity of those to whom they belonged. Relics of Saint Teresa of Avila were so valued, for example, that when her body was exhumed for canonization in 1622, clerics smuggled away her fingers and toes, sometimes in their mouths. But there are secular relics as well, from clippings of Marie Antoinette’s hair to the preserved corpse of Vladimir Lenin. Through sheer proximity to these relics, the faithful feel the full solemnity of the deceased’s presence and their greater impact on history. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz never finished the principal task assigned to him by his boss, Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover. When the latter became King of England in 1704 –the beginning of the ‘Hanoverian usurpation’ that still enjoys some sort of power in the United Kingdom and some of its former possessions–, Leibniz, the delinquent court genealogist, was not invited to join him, as he had hoped. Instead he was made to stay behind, in the expectation that he would finally complete his long overdue history of the medieval origins of Georg Ludwig’s own Guelf family, and of their distant union with the Italian Este dynasty: a forgotten alliance that, once reestablished, might yield up validation for new territorial claims.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz never finished the principal task assigned to him by his boss, Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover. When the latter became King of England in 1704 –the beginning of the ‘Hanoverian usurpation’ that still enjoys some sort of power in the United Kingdom and some of its former possessions–, Leibniz, the delinquent court genealogist, was not invited to join him, as he had hoped. Instead he was made to stay behind, in the expectation that he would finally complete his long overdue history of the medieval origins of Georg Ludwig’s own Guelf family, and of their distant union with the Italian Este dynasty: a forgotten alliance that, once reestablished, might yield up validation for new territorial claims. Within every person’s mind there is on ongoing battle between reason and emotion. It’s not always a battle, of course; very often the two can work together. But at other times, our emotions push us toward actions that our reason would counsel against. Paul Bloom is a well-known psychologist and author who wrote the provocatively-titled book Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion, and is currently writing a book about the nature of cruelty. While I sympathize with parts of his anti-empathy stance, I try to stick up for the importance of empathy in the right circumstances. We have a great discussion about the relationship between reason and emotion.

Within every person’s mind there is on ongoing battle between reason and emotion. It’s not always a battle, of course; very often the two can work together. But at other times, our emotions push us toward actions that our reason would counsel against. Paul Bloom is a well-known psychologist and author who wrote the provocatively-titled book Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion, and is currently writing a book about the nature of cruelty. While I sympathize with parts of his anti-empathy stance, I try to stick up for the importance of empathy in the right circumstances. We have a great discussion about the relationship between reason and emotion. It was not an overt incident of racism that prompted Edray Goins, an African-American mathematician in the prime of his career, to abandon his tenured position on the faculty of a major research university last year.

It was not an overt incident of racism that prompted Edray Goins, an African-American mathematician in the prime of his career, to abandon his tenured position on the faculty of a major research university last year. I met

I met  In her work, rage is authority; her imperious voice and dirty mouth make for a feminist literature empty of caveats and equivocation. And reading her now, beyond the anti-porn intransigence she’s both reviled and revered for, one feels a prescient apocalyptic urgency, one perfectly calibrated, it seems, to the high stakes of our time. In the #MeToo era, women’s unsparing public testimony—in granular detail and dizzying quantity—is at the heart of a mainstream cultural reckoning with sexual violence and harassment. Such frank accounts were not at the forefront, though, or even in the picture, of early second-wave feminism. Dworkin’s emergence as a militant figure of the women’s movement in New York was part of a turn: she was one of the first writers to use her own experiences of rape and battery in a revolutionary analysis of male supremacy. This is not to say that Dworkin’s books are all autobiographical, but in all of her work—from her frequently cited polemics to her desolate, little-known works of autofiction—she boldly identifies herself with victims, unafraid to brand herself with an image of female abjection and sexual shame in the name of justice.

In her work, rage is authority; her imperious voice and dirty mouth make for a feminist literature empty of caveats and equivocation. And reading her now, beyond the anti-porn intransigence she’s both reviled and revered for, one feels a prescient apocalyptic urgency, one perfectly calibrated, it seems, to the high stakes of our time. In the #MeToo era, women’s unsparing public testimony—in granular detail and dizzying quantity—is at the heart of a mainstream cultural reckoning with sexual violence and harassment. Such frank accounts were not at the forefront, though, or even in the picture, of early second-wave feminism. Dworkin’s emergence as a militant figure of the women’s movement in New York was part of a turn: she was one of the first writers to use her own experiences of rape and battery in a revolutionary analysis of male supremacy. This is not to say that Dworkin’s books are all autobiographical, but in all of her work—from her frequently cited polemics to her desolate, little-known works of autofiction—she boldly identifies herself with victims, unafraid to brand herself with an image of female abjection and sexual shame in the name of justice. One afternoon in June 1999, more than three million Chinese schoolchildren took their seats for the Gaokao, the country’s national college entrance exam. Essay subjects in previous years had been patriotic – “the most touching scene from the Great Leap Forward” (1958) – or prosaic –“trying new things” (1994) – but the final essay question of the millennium was a vision of the future: “what if memories could be transplanted?”

One afternoon in June 1999, more than three million Chinese schoolchildren took their seats for the Gaokao, the country’s national college entrance exam. Essay subjects in previous years had been patriotic – “the most touching scene from the Great Leap Forward” (1958) – or prosaic –“trying new things” (1994) – but the final essay question of the millennium was a vision of the future: “what if memories could be transplanted?” ELY, Nev. — A crew of five wildlife biologists wearing overalls, helmets and headlamps walked up the flanks of a juniper-studded mountain and climbed through stout steel bars to enter an abandoned mine that serves as a bat hibernaculum.

ELY, Nev. — A crew of five wildlife biologists wearing overalls, helmets and headlamps walked up the flanks of a juniper-studded mountain and climbed through stout steel bars to enter an abandoned mine that serves as a bat hibernaculum. More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us

More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us  Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?