Garrett Felber in Boston Review:

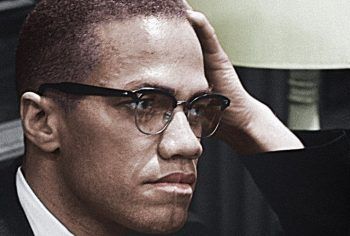

More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us in these pageson the fiftieth anniversary of King’s death this year, “There are costs to canonization.” The primary vehicle of canonization in Malcolm’s case has been The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which has been translated into thirty languages and has been widely read—by students and activists alike—across the United States and abroad.

More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us in these pageson the fiftieth anniversary of King’s death this year, “There are costs to canonization.” The primary vehicle of canonization in Malcolm’s case has been The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which has been translated into thirty languages and has been widely read—by students and activists alike—across the United States and abroad.

…There have long been rumors of three missing chapters among scholars; some think Haley cut them from the book following Malcolm’s assassination because their politics diverged or the book had transformed during his tumultuous last year. Whatever the reasoning, “The Negro” is a fragment of the book Malcolm intended to publish—a book that would be virtually unrecognizable to readers of his autobiography today. We will never fully know that book, of course, but “The Negro” chapter forces us, finally, to engage with it.

…In “The Negro,” he called Democrats and Republicans “labels that mean nothing” to black people. Elsewhere he noted how in the United Nations, there are those who vote yes, those who vote no, and those who abstain. And those who abstain often “have just as much weight.” A sign of political maturity, he believed, was to first register black people, then organize them, and vote only when a candidate represented their interests.

This analysis culminated in one of Malcolm’s most famous addresses, “The Ballot or the Bullet.” Delivered in April 1964 shortly after breaking with the Nation of Islam and forming his independent organization Muslim Mosque, Inc., Malcolm told a Cleveland audience, “A ballot is like a bullet. You don’t throw your ballots until you see a target, and if that target is not within your reach, keep your ballot in your pocket.” Many historians have seen the speech as Malcolm’s first ideological break from the Nation of Islam, an index of his developing political thought. “The Negro,” by contrast, shows this thought as an extension of the Nation of Islam’s political development rather than a departure. Even the title of his speech may have been borrowed from the pages of Muhammad Speaks; in 1962, a front-page story about the struggle in Fayette County, Tennessee, to register black voters was subtitled: “Fayette Fought For Freedom With Bullets and Ballots.”

More here. (Note: Throughout February, we will publish at least one post dedicated to Black History Month)

ELY, Nev. — A crew of five wildlife biologists wearing overalls, helmets and headlamps walked up the flanks of a juniper-studded mountain and climbed through stout steel bars to enter an abandoned mine that serves as a bat hibernaculum.

ELY, Nev. — A crew of five wildlife biologists wearing overalls, helmets and headlamps walked up the flanks of a juniper-studded mountain and climbed through stout steel bars to enter an abandoned mine that serves as a bat hibernaculum. More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us

More than fifty years after his death, Malcolm X remains a polarizing and misunderstood figure. Not unlike the leader he is too often contrasted with—Martin Luther King, Jr.—he has been a symbol to mobilize around, a foil to abjure, or a commodity to sell, rather than a thinker to engage. As political philosopher Brandon Terry reminded us  Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

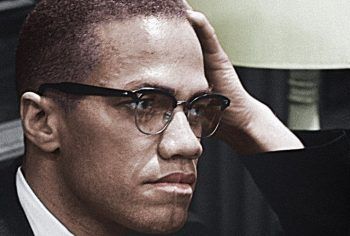

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.

History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events.

History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events. A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann)

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann) impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

Michael E Mann is one of two climate scientists who have been awarded the 2019

Michael E Mann is one of two climate scientists who have been awarded the 2019  One thing that should be said about Representative Ilhan Omar’s tweet about the power of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (more commonly known as AIPAC, or the “Israel lobby”) is that the hysterical reaction to it proved her main point: The power of AIPAC over members of Congress is literally awesome, although not in a good way. Has anyone ever seen so many members of Congress, of both parties, running to the microphones and sending out press releases to denounce one first-termer for criticizing the power of… a lobby?

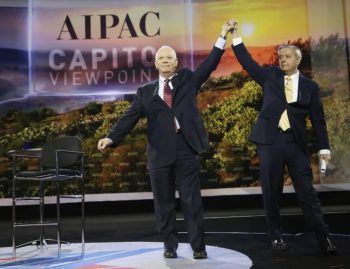

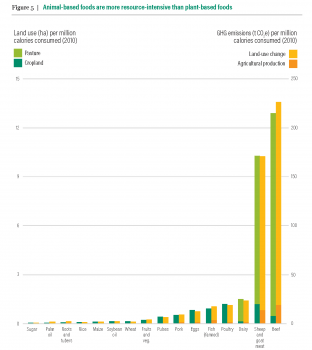

One thing that should be said about Representative Ilhan Omar’s tweet about the power of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (more commonly known as AIPAC, or the “Israel lobby”) is that the hysterical reaction to it proved her main point: The power of AIPAC over members of Congress is literally awesome, although not in a good way. Has anyone ever seen so many members of Congress, of both parties, running to the microphones and sending out press releases to denounce one first-termer for criticizing the power of… a lobby? For decades, environmentalists have been rightly concerned about the environmental impact of humanity’s food systems. Often, this has meant advocating for shifting diets — in particular, away from meat, given its outsized environmental impact.

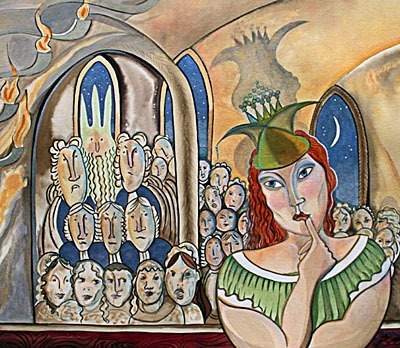

For decades, environmentalists have been rightly concerned about the environmental impact of humanity’s food systems. Often, this has meant advocating for shifting diets — in particular, away from meat, given its outsized environmental impact. SATIRES OF THE ART WORLD

SATIRES OF THE ART WORLD