by Ali Minai

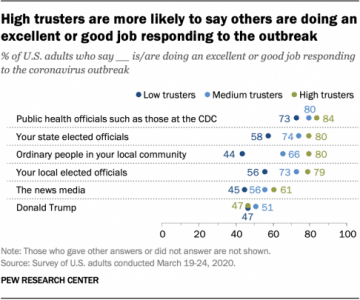

Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague.

Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague.

The most important lesson that the current calamity should teach every one of us is humility, though it will surely fail to do so until it is too late. The armchair thinker, however, has the luxury of indulging in the vanity of speculation without risking anything more than a proverbial dish of crow – delivered, one hopes, untouched by human hands and at a safe distance. But the time for that will come later, in a different world with different delicacies and intimacies. This is a message from the “here and now.”

So what will the world come to?

The biggest – and totally unknown – factor that will influence the answer to this question is the future course of the pandemic. Broadly there are four possibilities:

- An effective vaccine or prophylactic is found by late 2020 and is deployed worldwide by next spring, resulting in virtual eradication of the SARS Cov-2 virus sometime in 2021.

- No vaccine or prophylactic is found soon, but a post-infection treatment is developed by early 2021 so that COVID-19 becomes a treatable disease – possibly at significant expense and/or inconvenience.

- Finding a preventive or treatment takes much longer than a year, resulting in a second, third, and more waves of infections before something usable is found or herd immunity develops everywhere.

- No preventive or treatment is found, and herd immunity fails to develop for some reason.

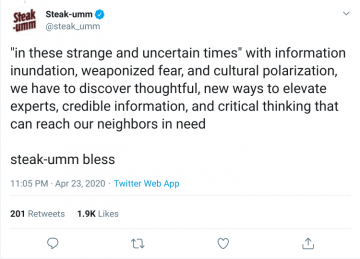

Possibility 4 is the stuff of apocalypse, so let us assume that it is extremely unlikely. Possibility 1 is conceivable given the scientific firepower being directed at the problem, but seems rather optimistic. If it does come to pass, most things will probably go back to the way they were in November 2019, leaving behind a detritus to bankrupt businesses, lost jobs, disrupted lives, and a deep economic recession. Possibility 2 has similar prospects, but would lead to more significant changes in areas such as work patterns, wearing of masks, large gatherings, etc. The more realistic possibility is number 3, which will have a profound effect on humanity. Going through such an extended trauma will alter life in ways that defy imagination. While humanity waits on science, uncertainty will grip the world. Everything – social interaction, work, education, healthcare, entertainment, sports, travel, politics, business, the media –will change so much during this time that it will be impossible to return to earlier ways. Read more »

What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.

What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story.

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story. One of the things that fascinates me about history is the different ways we know historical periods. We know the times we live through in a very deep way, not just the events and how they affect us, but the details of daily life. We know the slang, the jokes, the mid-list books; the forgettable songs and the ephemeral news; what the world smells like and how it tastes and sounds. It’s very hard to know another time period in anything like the detail we know our own: what people wore to work, what they did on Saturday afternoons, what all the machines did and why they were made.

One of the things that fascinates me about history is the different ways we know historical periods. We know the times we live through in a very deep way, not just the events and how they affect us, but the details of daily life. We know the slang, the jokes, the mid-list books; the forgettable songs and the ephemeral news; what the world smells like and how it tastes and sounds. It’s very hard to know another time period in anything like the detail we know our own: what people wore to work, what they did on Saturday afternoons, what all the machines did and why they were made.

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.