by Joan Harvey

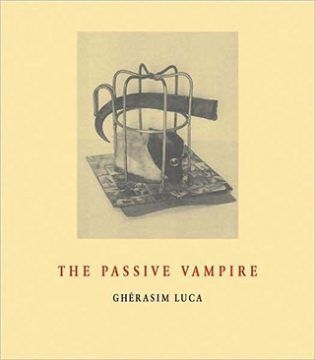

The Passive Vampire by Ghérasim Luca, 1945. Translated into English by Krzysztof Fijalkowski (Prague, Twisted Spoon Press, 2008)

If it is true, as is claimed

that after death man continues

a phantom existence

I’ll let you know.

Ghérasim Luca, La Mort morte, 1941

Vive le vampire!

James Joyce, Ulysses

A book travels through time, disappears, reappears, and bites. Bites a reader who exists in a completely different time and space. Does this bite draw blood? As I read I get goosebumps, even in 100-degree heat.

The Passive Vampire turns up here in Utah, a Utah of rocks and Mormons, Navajos and uranium, coyotes and bats, “a net of bats cleaving our destinies together to a slender, delirious wire.” (P.V. 103) Bats, vampires, things that bite in the night. We live here in a visual delirium of stone and color, vast blue space, green valleys, red rocks, orange rocks, purple rocks in all manner of outrageous formations, and heat, dry heat. Reality itself is surreal. Though the water of the Colorado River seems far from the water of the Seine where Luca drowned himself.

Here, in this house, in this desert landscape, I’m bored with the whole idea of vampires, although they keep multiplying, turning up everywhere. I once bought a house from America’s foremost vampire theoretician. (Was it haunted? Of course.) I have even been a vampire in a movie called Who Killed JonBenét?, a film that from production descended directly into a crypt. I thought I made a surprisingly good vampire, but all images have been lost.

But a passive vampire is something else. A passive vampire gives blood as well as takes it. Is this passive vampire “sadomasochistically confused,” as Luca says, or perhaps, as well, a generous vampire?

He is at any rate, a surrealist vampire, from a time when surrealism seemed, as Walter Benjamin put it, “the most integral, conclusive, absolute of movements.”[i] This passive vampire is surprisingly un-un-dead. He comes to us in writing of raw freshness, nakedness, newness, and dream. He comes out of Bucharest, via Paris, then into this translation into English through a publishing house in Prague. Arrives in this new fetish-object book, creamy and filled with repelling/compelling photos. He gives gifts of objects made from mutilated dolls (had Luca seen those of Hans Bellmer in the surrealist journal Minotaur?) and razor blades, and he is also willing to give us himself: “And my great, my supreme desire to spill blood, to dive into a bath of blood, to drink blood, to breathe blood, how could I understand this desire without the sacrifice of blood which I am ready to make.” (P.V. 83)

In vampire mythology there is a phrase, “going to ground,” which is used to describe an extended period of sleep, when the vampire retreats. This ‘hibernation’ forms a break between the vampire’s various lifetimes, and is often undertaken in a state of despair, when circumstances or feelings threaten to overwhelm the vampire or expose its true identity.[ii] The original version of The Passive Vampire appeared in 1945 in only 460 copies, plus 41 more in deluxe format.[iii] 56 years passed before it reappeared in France, reissued by José Corti in 2001. Eight years later it made its way into English. Each time it resurfaces the number of its willing victims grows.

The Passive Vampire introduces and is introduced by a series of Luca’s OOO’s, objectively offered objects, another form of disturbing generosity. When is generosity disturbing? These strange and mutilated objects bestowed as gifts work to subvert the mass-produced consumer object; they expose and create new elements of relationship. A woman, H., asks Luca for a ball studded with nails that she sees lying in his room. He sees this first as a “love-object,” then as a sign of the woman’s desire to castrate him, a desire which he then transforms again through an attached text, to “love object.”

(After I read The Passive Vampire I discovered that Tim Morton has been developing a philosophical movement he calls object-oriented ontology or OOO. Morton does not mention Luca’s OOOs; no doubt he had not heard of them. It seems OOOs are using our texts to resurface in different forms, objects coming back to bite us, Luca’s objects idiosyncratic and relationship-altering, Morton’s “massively distributed in time and space relative to humans.”[iv])

A vampire subverts time, is always one age and yet gets older, is partly dead and never dead, has his own half-life. Luca is a real corpse, but I feed on him, on the sound of his recorded voice, on the texts that come to us in one language or another. I consume his verbs, eat his daisies, daisies that give us the radical choice: “She loves me or she loves me.” He gives us his blood, his vampire mind, and steals our thoughts. He turns up in the land of the Mormon and Navajo. Who have their own relationship to half-lives.

In Utah I dream a man in a hat is up to something no good. Maybe spreading uranium around. I’m shadowing him secretly. “The oneiric image projects itself, shifts, vanishes, and its almost spatial reality is made manifest in the pocket of mist cast far in the distance.”(P.V. 105) In their creation myth Navajos were given the choice between two yellow substances, corn and uranium, called “yellowcake.” They correctly chose corn. Uranium was thought of as an element of the underworld to be left underground. If released it will become a serpent and cause death and destruction. Depleted uranium actually becomes more radioactive as the centuries and millennia go by because its decay products accumulate. Uranium decays into, among other things, radon, which causes lung cancer; radium, which causes bone cancer, cancer of the sinuses, and leukemia; and thorium, which can cause increased risk of lung and pancreatic cancer. Depleted uranium can also cause birth defects and damage to the kidneys.

Mark Yellowhair, a Navajo whose hair is not now and never has been yellow, did some work for us, briefly. As a kid he ran barefoot, herding lizards and chasing sheep in 100-degree weather. His laugh is a kind of yip like the howl of a coyote. His first wife died from ovarian cancer, the only woman he really ever loved. The Navajo reservation where Mark Yellowhair lives is only a small portion of the land that once was the Navajos’; their lives and culture have been depleted by ours. And though the reservation land is poor, it is rich in uranium and, because jobs are few, the Navajo worked for years in the mines.

After Mark Yellowhair’s wife died from cancer, he told us, he went mad, couldn’t be with himself, couldn’t be alone and took up drinking. He got arrested again and again until he ended up in jail. This was years ago. But Mark Yellowhair is still living on the edge. Always borrowing money from us. He tells us, “If you can’t trust someone there’s no relationship.” Then he steals our tools and takes them to the pawnshop.

Luca made violent gifts and gave them away. Mark Yellowhair steals our tools, and places them temporarily out of circulation in the pawnshop, where they cannot be used. Both of them subvert our normal relations to objects. We track the tools down, get them back, tell him never to set foot here again. We have to warn our neighbor who wanted to hire him as well. Mark won’t fit into our ideas of how people should behave, he shows us he’s not our friend, he won’t be a laborer, passed around from house to house. He takes himself out of circulation. All part of a cycle, of death and resistance to death.

The Passive Vampire was first published in 1945. This was the year of The Gadget, the first of the atom bombs, and what Tim Morton calls the beginning of the Great Acceleration. Interest in uranium mining in the U.S. really only got underway during WWII as part of the war effort to defeat the Nazis. The effort to defeat evil contained its own evil. There was a lot of money to be made in uranium and lots of expendable Navajos. On both sides of the ocean marginalized peoples were being destroyed. A linkage of then to now, here to there, a Jewish surrealist in Bucharest to a Navajo worker in Utah.

Surrealist blood goes underground but re-surfaces in new bodies, new geographies, new historical forms. Luca wrote The Passive Vampire in a city controlled by the pro-Nazi Iron Guard, and, as a Jew and member of the avant-garde, his situation was perilous. While his main quest was “the reinvention of love,” during his life he left five suicide notes on different occasions, and finally did kill himself when he threw himself into the Seine. But the blood of his passive vampiric double lives on, negating his negations and turning up on other continents by chance, which, as Luca says, “alone ceaselessly offers us the possibility of discovering the contradictions of a society divided along class lines.”

Surrealism attempted an alternative politics to fascism, to colonialism, and to the vampirism of capitalism, an attempted politics that has been buried, gone to ground, but that doesn’t die. We can juxtapose an objectively offered object OOO with an object-oriented ontology OOO, can link a Navajo to a Romanian Jew, can give them their chance meeting in a text, offering one object to another, one past to another, and infuse them with blood, with love. We can’t duplicate the old surrealist methods, but, being bitten, we can take them in and be transformed. Take a chance of life in the culture of death, in the wild laugh of Mark Yellowhair.

We must, in turn, give our own ink (or blood) to the greater book, written, as Luca says, “on the black paper of the unknown.”

[i] Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism” in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings Trans. Edmund Jephcott, (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978) p. 178

[ii]“Nursery fears made flesh and sinew. Vampires, the Body and Eating Disorders: A Psychoanalytic Approach” ©Sally Miller, Royal College of Art, London 1999 http://homepages.nildram.co.uk/~beast/publications/vamp_paper/psychoanalysis.html#return15

[iii] Intro to P.V. p. 16

[iv] Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2013) 1