Blake Morris in Nautilus:

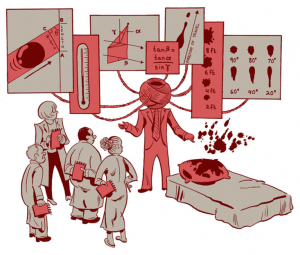

By the time Donald Johnson got the call to come to the crime scene, the victim had been dead for hours. A first responder opened the apartment door to find a woman lying on the edge of her bed, nude from the waist down, bound and gagged with duct tape. She had been bludgeoned to death. The homicide detectives needed an expert to gather the evidence. That was where Johnson came in. Then a senior criminalist for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Johnson surveyed the apartment. Shards of ceramic lay on the kitchen floor, remnants from a broken jar that once held flour. Johnson noticed two sets of footprints in the flour, ignaling to him that there were two assailants. Clothes spilled from a chest against the wall across from the bed. From the mangled lock, Johnson could tell the chest had been forcibly opened, perhaps with a crowbar. There was also blood on the lock, with a trail of drops on the floor leading to the sink where the assailant had washed his hands.

By the time Donald Johnson got the call to come to the crime scene, the victim had been dead for hours. A first responder opened the apartment door to find a woman lying on the edge of her bed, nude from the waist down, bound and gagged with duct tape. She had been bludgeoned to death. The homicide detectives needed an expert to gather the evidence. That was where Johnson came in. Then a senior criminalist for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Johnson surveyed the apartment. Shards of ceramic lay on the kitchen floor, remnants from a broken jar that once held flour. Johnson noticed two sets of footprints in the flour, ignaling to him that there were two assailants. Clothes spilled from a chest against the wall across from the bed. From the mangled lock, Johnson could tell the chest had been forcibly opened, perhaps with a crowbar. There was also blood on the lock, with a trail of drops on the floor leading to the sink where the assailant had washed his hands.

It was more than enough blood evidence for Johnson to get a complete DNA profile.

This ghastly crime happened 28 years ago, but a replica of the scene is on display in a classroom at the Hertzberg-Davis Forensic Science Center at California State University, Los Angeles, where Johnson, 60, has worked as an associate professor in the criminalistics program since 2003, and is currently working on new forensic technology called the Spatter Origin Revealing System to improve how investigators can solve crimes by examining blood. Aside from serving students, the Forensic Science Center is also the working crime lab for the Los Angeles Police Department and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. As the largest crime lab in the country, second only to the F.B.I.’s, the Forensic Science Center conducts DNA analysis, questionable documents analysis, narcotics testing, trace evidence analysis, and ballistics testing, in addition to blood spatter analysis. For teaching purposes, Johnson often recreates real crime scenes that he worked on as a criminalist before he left the field in 2003. For this one he used a mannequin and sterilized pig blood.

More here.