Melanie McFarland in Salon:

“Castle Rock,” Hulu’s longform series ode to Stephen King debuting Wednesday, is a reminder of how differently people can view the same story. By no means is it a “Rashomon”-type of affair; King’s commercial success is rooted in the fact that his stories are straightforward entertainments, with meanings no more complex than the eternal struggles between light and dark or good versus evil. The same applies to “Castle Rock,” a original creation by Sam Shaw (“Manhattan”) and Dustin Thomason, that is foremost a fairly straightforward pastiche of the horror author’s oeuvre. Those who are well-versed in King’s work, whether on the page or by way of one of the 100-plus screen adaptations of his stories — may welcome the Easter egg hunt it offers by dotting each episode with details and character associations from previous works. The most obvious is the town itself. The average filmgoer is much more likely to recognize the second most important character in Castle Rock other than the town itself: Shawshank State Penitentiary. Even those familiar with King by reputation and little else should recognize the classic narrative of the prodigal son returned, personified here in Henry Deaver.

“Castle Rock,” Hulu’s longform series ode to Stephen King debuting Wednesday, is a reminder of how differently people can view the same story. By no means is it a “Rashomon”-type of affair; King’s commercial success is rooted in the fact that his stories are straightforward entertainments, with meanings no more complex than the eternal struggles between light and dark or good versus evil. The same applies to “Castle Rock,” a original creation by Sam Shaw (“Manhattan”) and Dustin Thomason, that is foremost a fairly straightforward pastiche of the horror author’s oeuvre. Those who are well-versed in King’s work, whether on the page or by way of one of the 100-plus screen adaptations of his stories — may welcome the Easter egg hunt it offers by dotting each episode with details and character associations from previous works. The most obvious is the town itself. The average filmgoer is much more likely to recognize the second most important character in Castle Rock other than the town itself: Shawshank State Penitentiary. Even those familiar with King by reputation and little else should recognize the classic narrative of the prodigal son returned, personified here in Henry Deaver.

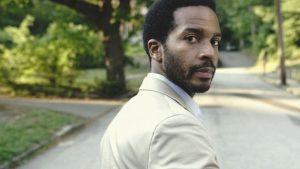

An attorney who specializes in death row cases, Deaver is lured back to Castle Rock at the behest of an unidentified caller. It’s not a trip he wants to take, but something prods him into going. Henry could be thought of the spiritual sibling to Selena St. George, the accusatory daughter in the film adaptation of “Dolores Claiborne.” Like Selena, it’s implied that Henry left town to escape something in his past that the townsfolk won’t allow him to forget. But a key difference, besides their gender, is that Henry, played by Andre Holland, is black.

More here.