Micah’s Prophesy

.

Time subsides and you fall back into the hammock

of another easy truth. There are so many ways to

disguise this. One reigning idea dictates what you will

think, so you go blundering from one war to another,

one rape or abuse to another. My dream for you is clothed

with shadows. Listen,- your final dawn will arrive rudely.

What became of me wasn’t worth the telling. But, I’ll say

this: the real dungeons are our own words, the real chains

the ones we use to encircle our hearts. There are letters

in my alphabet you’ll never know. I saw a whole

army collapse like a huge lung. I saw bodies fall like

chips from a woodsman’s axe. There was a king who

believed me, and one who didn’t. You know their fates.

Your own kings pencil in their beliefs for later erasure.

After each tragedy they hand out antique apologies.

Someone shoots in a theater and soon it plays like fiction.

Someone else pulverizes symbols they don’t understand.

When you break the world it doesn’t just get fixed.

There is a truth, if you listen, but it arrives with no

postmark and no return address, no provision for revision.

Even your windows mutter things you refuse to understand.

I can say: there is little patience with your skeletal words.

I can say: you should already know this by reading

what has already been written on the dungeon walls of

your own hearts and the watermarks of your own souls.

The harp plays on, but the question is, who’s listening?

by Richard Jackson

from Echotheo Review

The cognitive revolution

The cognitive revolution In 1960, the literary critic Leslie Fiedler delivered a eulogy for the ghost story in his classic study “Love and Death in the American Novel.” “An obsolescent subgenre,” he declared, with conspicuous relish; a “naïve” little form, as outmoded as its cheap effects, the table-tapping and flickering candlelight. Ghost stories belong to — brace yourself for maximum Fiedlerian venom — “middlebrow craftsmen,” who will peddle them to a rapidly dwindling audience and into an extinction that can’t come soon enough.

In 1960, the literary critic Leslie Fiedler delivered a eulogy for the ghost story in his classic study “Love and Death in the American Novel.” “An obsolescent subgenre,” he declared, with conspicuous relish; a “naïve” little form, as outmoded as its cheap effects, the table-tapping and flickering candlelight. Ghost stories belong to — brace yourself for maximum Fiedlerian venom — “middlebrow craftsmen,” who will peddle them to a rapidly dwindling audience and into an extinction that can’t come soon enough.

Some of the scientists most often cited by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have taken the unusual step of

Some of the scientists most often cited by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have taken the unusual step of  NO WORKING WRITER believes in the shattering power of an encounter—with another person, with a new sensation, with possibility—more than Amélie Nothomb, the prolific Paris-based Belgian who’s published a novel a year since 1992’s Hygiène de l’assassin (rendered in English as Hygiene and the Assassin, though a more accurate title would be The Assassin’s Purity). Her first book offered an impressive blueprint of what would define her subsequent work: arrogant, infuriating personalities; vicious character clashes; childhood love so obsessive that it bleeds out over an adult’s entire history; and philosophical declarations about war. (Nothomb’s fervent worship of “war,” used to describe any grand conflict, is as distinctive a signature as her actual name.) “My books are more harmful than war,” brags the author at the center of Hygiene, “because they make you want to die, whereas war, in fact, makes you want to live.” His demeanor is so provoking that it incites murder, which is another Nothomb theme. People are always destroying one another. She’s killed a self-named avatar off on at least two separate occasions.

NO WORKING WRITER believes in the shattering power of an encounter—with another person, with a new sensation, with possibility—more than Amélie Nothomb, the prolific Paris-based Belgian who’s published a novel a year since 1992’s Hygiène de l’assassin (rendered in English as Hygiene and the Assassin, though a more accurate title would be The Assassin’s Purity). Her first book offered an impressive blueprint of what would define her subsequent work: arrogant, infuriating personalities; vicious character clashes; childhood love so obsessive that it bleeds out over an adult’s entire history; and philosophical declarations about war. (Nothomb’s fervent worship of “war,” used to describe any grand conflict, is as distinctive a signature as her actual name.) “My books are more harmful than war,” brags the author at the center of Hygiene, “because they make you want to die, whereas war, in fact, makes you want to live.” His demeanor is so provoking that it incites murder, which is another Nothomb theme. People are always destroying one another. She’s killed a self-named avatar off on at least two separate occasions.

To understand the literary Gothic – to even begin to account for its curious appeal, and its simultaneous qualities of seduction and repulsion – it is necessary to undertake a little time travel. We must go back beyond the builders putting the capstone on Pugin’s Palace of Westminster, and on past the last lick of paint on the iced cake of Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill House; back again another six hundred years past the rap of the stone-mason’s hammer on the cathedral at Reims, in order to finally alight on a promontory above the city of Rome in 410AD. The city is on fire. There are bodies in the streets and barbarians at the gates. Pope Innocent I, hedging his bets, has consented to a little pagan worship that is being undertaken in private. Over in Bethlehem, St Jerome hears that Rome has fallen. ‘The city which had taken the whole world’, he writes, ‘was itself taken.’ The old order – of decency and lawfulness meted out with repressive colonial cruelty – has gone. The Goths have taken the Forum.

To understand the literary Gothic – to even begin to account for its curious appeal, and its simultaneous qualities of seduction and repulsion – it is necessary to undertake a little time travel. We must go back beyond the builders putting the capstone on Pugin’s Palace of Westminster, and on past the last lick of paint on the iced cake of Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill House; back again another six hundred years past the rap of the stone-mason’s hammer on the cathedral at Reims, in order to finally alight on a promontory above the city of Rome in 410AD. The city is on fire. There are bodies in the streets and barbarians at the gates. Pope Innocent I, hedging his bets, has consented to a little pagan worship that is being undertaken in private. Over in Bethlehem, St Jerome hears that Rome has fallen. ‘The city which had taken the whole world’, he writes, ‘was itself taken.’ The old order – of decency and lawfulness meted out with repressive colonial cruelty – has gone. The Goths have taken the Forum. It’s dark. It’s cold. As I write this the rain is lashing down outside my window and beyond that – ugh! The world. Brexit, Trump, Putin. Danger, fear and uncertainty. I want warmth, I want comfort and I want to feel that somehow, somewhere, order might be restored. I want, in other words, to read a novel by

It’s dark. It’s cold. As I write this the rain is lashing down outside my window and beyond that – ugh! The world. Brexit, Trump, Putin. Danger, fear and uncertainty. I want warmth, I want comfort and I want to feel that somehow, somewhere, order might be restored. I want, in other words, to read a novel by  In the winter of 1994, a young man in his early twenties named Tim was a patient in a London psychiatric hospital. Despite a happy and energetic demeanour, Tim had bipolar disorder and had recently attempted suicide. During his stay, he became close with a visiting US undergraduate psychology student called Matt. The two quickly bonded over their love of early-nineties hip-hop and, just before being discharged, Tim surprised his friend with a portrait that he had painted of him. Matt was deeply touched. But after returning to the United States with portrait in hand, he learned that Tim had ended his life by jumping off a bridge.

In the winter of 1994, a young man in his early twenties named Tim was a patient in a London psychiatric hospital. Despite a happy and energetic demeanour, Tim had bipolar disorder and had recently attempted suicide. During his stay, he became close with a visiting US undergraduate psychology student called Matt. The two quickly bonded over their love of early-nineties hip-hop and, just before being discharged, Tim surprised his friend with a portrait that he had painted of him. Matt was deeply touched. But after returning to the United States with portrait in hand, he learned that Tim had ended his life by jumping off a bridge.  April 2018: ‘Tis the Season of Giddiness in Democratlandia. Republicans are saddled with a widely despised President and riven by internal dissension. The Republican leadership in Congress is lurching from fiasco to fiasco – interrupted briefly by one great “success” on tax cuts. The zombie candidates of the Tea Party are still stalking establishment Republicans across the land. And, somewhere in his formidable fastness, the Great Dragon Mueller is winding up for the fiery breath that will consume the world of Trumpism like a paper lantern. And a Blue Wave – nay, a Tsunami – is headed towards the Republicans in Congress, looking to engulf them in November.

April 2018: ‘Tis the Season of Giddiness in Democratlandia. Republicans are saddled with a widely despised President and riven by internal dissension. The Republican leadership in Congress is lurching from fiasco to fiasco – interrupted briefly by one great “success” on tax cuts. The zombie candidates of the Tea Party are still stalking establishment Republicans across the land. And, somewhere in his formidable fastness, the Great Dragon Mueller is winding up for the fiery breath that will consume the world of Trumpism like a paper lantern. And a Blue Wave – nay, a Tsunami – is headed towards the Republicans in Congress, looking to engulf them in November.

When you consume a meal, do you eat cow or beef? Yes, these are the same, especially considering where they end up, but we tend to think of the cow as the beginning of this particular process, and the beef as the product. More of these pairings include calf/veal, swine or pig/pork, sheep/mutton, hen or chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot.

When you consume a meal, do you eat cow or beef? Yes, these are the same, especially considering where they end up, but we tend to think of the cow as the beginning of this particular process, and the beef as the product. More of these pairings include calf/veal, swine or pig/pork, sheep/mutton, hen or chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot.

It could almost be a question on a very meta personality quiz: Do you prefer the Myers-Briggs typology or the Big Five personality traits? The Myers-Brigg Type Inventory is a popular tool that was developed outside of the scientific establishment by two women who did not have credentials in psychology. It’s qualitative rather than quantitative, and in the past decade or so, it’s been criticized as meaningless or unscientific. The Big Five taxonomy is widely accepted in academia and is the basis of much current personality research. It’s quantitative; in fact, it’s based on statistical analysis. Am I rejecting science if I continue to prefer the Myers-Briggs system as a key to understanding my own personality and those of others?

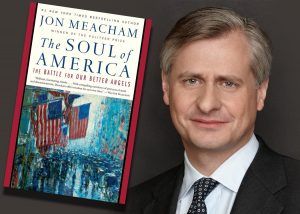

It could almost be a question on a very meta personality quiz: Do you prefer the Myers-Briggs typology or the Big Five personality traits? The Myers-Brigg Type Inventory is a popular tool that was developed outside of the scientific establishment by two women who did not have credentials in psychology. It’s qualitative rather than quantitative, and in the past decade or so, it’s been criticized as meaningless or unscientific. The Big Five taxonomy is widely accepted in academia and is the basis of much current personality research. It’s quantitative; in fact, it’s based on statistical analysis. Am I rejecting science if I continue to prefer the Myers-Briggs system as a key to understanding my own personality and those of others? It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.

It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.

Last fall, after a day spent hiking around the neighborhood, I ended up back on my porch with my buddy, Chef Mike. We were drinking beers and chatting about life.

Last fall, after a day spent hiking around the neighborhood, I ended up back on my porch with my buddy, Chef Mike. We were drinking beers and chatting about life.