Tom Standage in More Intelligent Life:

You are what you eat. The atoms in your body come from the food and drink you consume – and, to some extent, from the air you breathe. That is not terribly surprising. What few people realise, however, is that about half the nitrogen atoms in your body have passed through something called a Haber-Bosch reaction. This chemical process, invented just before the first world war, did as much to change the world during the 20th century as the atom bomb or the microchip. Its story deserves to be more widely known, because it offers hope today for a fight whose front line is fast approaching: the battle against climate change.

You are what you eat. The atoms in your body come from the food and drink you consume – and, to some extent, from the air you breathe. That is not terribly surprising. What few people realise, however, is that about half the nitrogen atoms in your body have passed through something called a Haber-Bosch reaction. This chemical process, invented just before the first world war, did as much to change the world during the 20th century as the atom bomb or the microchip. Its story deserves to be more widely known, because it offers hope today for a fight whose front line is fast approaching: the battle against climate change.

The tale begins with a dispute between two German chemists, which erupted at a conference in Hamburg in 1907. At the time, solidified bird excrement from South America, known as guano, was used around the world as fertiliser. Compared with manure, it contains 30 times more nitrogen, the key ingredient. Why not extract that element from the air, which is 78% nitrogen? Alas, nitrogen molecules are so stable and unreactive that chemists were having great difficulty getting them to combine with other elements. When Fritz Haber, a German scientist, reacted nitrogen with hydrogen to make ammonia, for example, only 0.0048% of the mixture combined. Walther Nernst, another German chemist, took issue with Haber’s results. The proportion of gas that combined, he calculated, ought to have been 0.0045%. Most people would have thought Haber’s figure was close enough, but not Nernst, who demanded that Haber withdraw his results. Greatly distressed at this rebuke, Haber concluded that repeating the experiment was the only way to restore his reputation. But when he did so, he discovered that performing the reaction at a higher pressure vastly increased the amount of ammonia produced: 10% of the mixture combined. This suggested that, rather than waiting for birds to do their business, fertiliser could be made directly from the atmosphere.

More here.

W

W The

The  I was particularly interested in sexuality and online porn. If, as Stephens-Davidowitz puts it, “Google is a digital truth serum,” then what else does it tell us about our private thoughts and desires? What else are we hiding from our friends, neighbors, and colleagues?

I was particularly interested in sexuality and online porn. If, as Stephens-Davidowitz puts it, “Google is a digital truth serum,” then what else does it tell us about our private thoughts and desires? What else are we hiding from our friends, neighbors, and colleagues? T

T In the 1970s and ’80s, Pittsburgh’s haunted-house scene was booming. Simmons remembers perusing long lists of Halloween happenings printed in the local newspaper, then grabbing twenty dollars and spending the whole night hopping between attractions. There were no websites or phone numbers; the haunted houses would stay open until people stopped showing up. The era of big-budget haunted houses didn’t exist yet, and almost all of them were for charity, run by volunteer fire departments, Elks Clubs, Make-A-Wish, and the United States Junior Chamber, also known as the Jaycees. The Jaycees’ haunted-house fundraisers became so successful that they circulated how-to manuals to their chapters nationwide; many experts credit the Jaycees with putting a haunted house in every city in America.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Pittsburgh’s haunted-house scene was booming. Simmons remembers perusing long lists of Halloween happenings printed in the local newspaper, then grabbing twenty dollars and spending the whole night hopping between attractions. There were no websites or phone numbers; the haunted houses would stay open until people stopped showing up. The era of big-budget haunted houses didn’t exist yet, and almost all of them were for charity, run by volunteer fire departments, Elks Clubs, Make-A-Wish, and the United States Junior Chamber, also known as the Jaycees. The Jaycees’ haunted-house fundraisers became so successful that they circulated how-to manuals to their chapters nationwide; many experts credit the Jaycees with putting a haunted house in every city in America. Many readers will be tempted to skip over the first 700 pages of this volume, to go straight for the final months. But that would be a big mistake. To begin with, the letters to Beuscher – Sylvia proposes rather poignantly at one point to pay her for her replies – need to be understood within a wider context of letter-writing patterns. The first volume of letters began at summer camp and ended with Sylvia and Ted’s honeymoon. The second begins in Cambridge in October 1956: Sylvia is studying for the second year of the English BA degree on a Fulbright scholarship; Ted, two years after graduating from Cambridge himself, is teaching at a boys’ school but “may have to take a labouring job” to cover the bills. They drink sherry, paint their shabby flat in cheerful colours, wait “breathlessly” for the post, heat milk for coffee (allowing the pan to boil over when it in fact arrives), recite Chaucer to the cows, and ask their omnipresent Ouija board when they will be published in the New Yorker. There is a huge amount about cooking and baking, including a request for Aurelia to send extra boxes of Flako pie crust mix across the Atlantic, a discussion of Ted’s love of casseroles, and the comment that “My Joy of Cooking is a blessing”. Really? A blessing? In her journal of the same year, Sylvia had rebuked herself wryly for reading The Joy of Cooking like a “rare novel”. “Whoa, I said to myself. You will escape into domesticity & stifle yourself by falling headfirst into a bowl of cookie batter.”

Many readers will be tempted to skip over the first 700 pages of this volume, to go straight for the final months. But that would be a big mistake. To begin with, the letters to Beuscher – Sylvia proposes rather poignantly at one point to pay her for her replies – need to be understood within a wider context of letter-writing patterns. The first volume of letters began at summer camp and ended with Sylvia and Ted’s honeymoon. The second begins in Cambridge in October 1956: Sylvia is studying for the second year of the English BA degree on a Fulbright scholarship; Ted, two years after graduating from Cambridge himself, is teaching at a boys’ school but “may have to take a labouring job” to cover the bills. They drink sherry, paint their shabby flat in cheerful colours, wait “breathlessly” for the post, heat milk for coffee (allowing the pan to boil over when it in fact arrives), recite Chaucer to the cows, and ask their omnipresent Ouija board when they will be published in the New Yorker. There is a huge amount about cooking and baking, including a request for Aurelia to send extra boxes of Flako pie crust mix across the Atlantic, a discussion of Ted’s love of casseroles, and the comment that “My Joy of Cooking is a blessing”. Really? A blessing? In her journal of the same year, Sylvia had rebuked herself wryly for reading The Joy of Cooking like a “rare novel”. “Whoa, I said to myself. You will escape into domesticity & stifle yourself by falling headfirst into a bowl of cookie batter.” We will soon be able to identify the likelihood that a newborn baby – perhaps your baby – will be susceptible to depression, anxiety and schizophrenia throughout his or her life. We will know the probability that our newborns will have difficulty learning to read, become obese and be prone to Alzheimer’s disease in their later years. Good news? Robert Plomin thinks so. In Blueprint, he argues such insights should make us more tolerant of those who might be overweight or prone to depression; they will enable us to support our children better and plan for our own life’s course. He is equally pleased with the discovery that much of what we think of as nurture – the caring, supporting environments we build for our children – has, on average, no impact on our loved ones’ development. Plomin explains that nurture in the home is as irrelevant as the school environment for influencing whether we become kind or gritty, happy or sad, wealthy or poor, and that this leads to greater equality of opportunity than would have otherwise been the case. The only thing that matters for our personalities and much else is the DNA that we inherit and those chance events of our lives beyond anyone’s control.

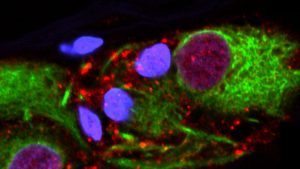

We will soon be able to identify the likelihood that a newborn baby – perhaps your baby – will be susceptible to depression, anxiety and schizophrenia throughout his or her life. We will know the probability that our newborns will have difficulty learning to read, become obese and be prone to Alzheimer’s disease in their later years. Good news? Robert Plomin thinks so. In Blueprint, he argues such insights should make us more tolerant of those who might be overweight or prone to depression; they will enable us to support our children better and plan for our own life’s course. He is equally pleased with the discovery that much of what we think of as nurture – the caring, supporting environments we build for our children – has, on average, no impact on our loved ones’ development. Plomin explains that nurture in the home is as irrelevant as the school environment for influencing whether we become kind or gritty, happy or sad, wealthy or poor, and that this leads to greater equality of opportunity than would have otherwise been the case. The only thing that matters for our personalities and much else is the DNA that we inherit and those chance events of our lives beyond anyone’s control. The appendix has a reputation of being useless at best. We tend to ignore this pinkie-size pouch dangling off our large intestine unless it gets inflamed and needs cutting out. But a new study suggests this enigmatic organ in the gut harbors a supply of a brain-damaging protein involved in Parkinson’s disease—even in healthy people. The study is the largest yet to find that an appendectomy early in life can decrease a person’s risk of Parkinson’s or delay its onset. “It plays into this whole booming field of whether Parkinson’s possibly starts in the gut,” says Per Borghammer, a neuroscientist at Aarhus University in Denmark who was not involved in the study. “And that would be a radical change in our understanding of the disease.” Look inside the brain of a person with Parkinson’s and you’ll find clumps of a misfolded form of a protein known as α-synuclein (αS). The protein’s normal function isn’t fully clear, but in this clumpy state, it may damage and kill neurons, including those near the base of the brain that help control movement. The results are the hallmark tremors and body rigidity of Parkinson’s.

The appendix has a reputation of being useless at best. We tend to ignore this pinkie-size pouch dangling off our large intestine unless it gets inflamed and needs cutting out. But a new study suggests this enigmatic organ in the gut harbors a supply of a brain-damaging protein involved in Parkinson’s disease—even in healthy people. The study is the largest yet to find that an appendectomy early in life can decrease a person’s risk of Parkinson’s or delay its onset. “It plays into this whole booming field of whether Parkinson’s possibly starts in the gut,” says Per Borghammer, a neuroscientist at Aarhus University in Denmark who was not involved in the study. “And that would be a radical change in our understanding of the disease.” Look inside the brain of a person with Parkinson’s and you’ll find clumps of a misfolded form of a protein known as α-synuclein (αS). The protein’s normal function isn’t fully clear, but in this clumpy state, it may damage and kill neurons, including those near the base of the brain that help control movement. The results are the hallmark tremors and body rigidity of Parkinson’s. Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s 200-year-old creature is more alive than ever. In his new role as the bogeyman of artificial intelligence (AI), ‘the monster’ made by Victor Frankenstein is all over the internet. The British literary critic Frances Wilson even

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s 200-year-old creature is more alive than ever. In his new role as the bogeyman of artificial intelligence (AI), ‘the monster’ made by Victor Frankenstein is all over the internet. The British literary critic Frances Wilson even  HALLOWEEN IS THE ONE

HALLOWEEN IS THE ONE  When we consider the future that technological change will bring about, it is tempting to envision a world taken over by robots, where the singularity has given way to superintelligent agents and human extinction. This is the image of our future we have grown accustomed to seeing in cinematic depictions, but it is not the future that British barrister Jamie Susskind wants us to worry about. Instead, in Future Politics: Living Together in a World Transformed by Tech, Susskind focuses on how digital technologies control human life rather than eliminate it.

When we consider the future that technological change will bring about, it is tempting to envision a world taken over by robots, where the singularity has given way to superintelligent agents and human extinction. This is the image of our future we have grown accustomed to seeing in cinematic depictions, but it is not the future that British barrister Jamie Susskind wants us to worry about. Instead, in Future Politics: Living Together in a World Transformed by Tech, Susskind focuses on how digital technologies control human life rather than eliminate it. In the summer of 1996, during an international anthropology conference in southeastern Brazil, Bruno Latour, France’s most famous and misunderstood philosopher, was approached by an anxious-looking developmental psychologist. The psychologist had a delicate question, and for this reason he requested that Latour meet him in a secluded spot — beside a lake at the Swiss-style resort where they were staying. Removing from his pocket a piece of paper on which he’d scribbled some notes, the psychologist hesitated before asking, “Do you believe in reality?”

In the summer of 1996, during an international anthropology conference in southeastern Brazil, Bruno Latour, France’s most famous and misunderstood philosopher, was approached by an anxious-looking developmental psychologist. The psychologist had a delicate question, and for this reason he requested that Latour meet him in a secluded spot — beside a lake at the Swiss-style resort where they were staying. Removing from his pocket a piece of paper on which he’d scribbled some notes, the psychologist hesitated before asking, “Do you believe in reality?”

“The war has left its imprint in our souls [with] all these visions of horror it has conjured up around us,” wrote French author Pierre de Mazenod in 1922, describing the Great War. His word, horreur, appears in various forms in an incredible number of accounts of the war, written by English, German, Austrian, French, Russian, and American veterans. The years following the Great War became the first time in human history the word “horror” and its cognates appeared on such a massive scale. Images of catastrophe abounded. The Viennese writer Stefan Zweig, one of the stars in the firmament of central Europe’s decadent and demonic café culture before 1914, wrote of how “bridges are broken between today and tomorrow and the day before yesterday” in the conflict’s wake. Time was out of joint. When not describing the war as horror, the imagery of all we would come to associate with the word appeared. One French pilot passing over the ruined city of Verdun described the landscape as a haunted waste and a creature of nightmare, “the humid skin of a monstrous toad.”

“The war has left its imprint in our souls [with] all these visions of horror it has conjured up around us,” wrote French author Pierre de Mazenod in 1922, describing the Great War. His word, horreur, appears in various forms in an incredible number of accounts of the war, written by English, German, Austrian, French, Russian, and American veterans. The years following the Great War became the first time in human history the word “horror” and its cognates appeared on such a massive scale. Images of catastrophe abounded. The Viennese writer Stefan Zweig, one of the stars in the firmament of central Europe’s decadent and demonic café culture before 1914, wrote of how “bridges are broken between today and tomorrow and the day before yesterday” in the conflict’s wake. Time was out of joint. When not describing the war as horror, the imagery of all we would come to associate with the word appeared. One French pilot passing over the ruined city of Verdun described the landscape as a haunted waste and a creature of nightmare, “the humid skin of a monstrous toad.” The mesmeric work of Lou Harrison (1917–2003) stands apart from so much of the music written in 20th-century America—so singular is its idiom, so striking are its borderless, cross-cultural sounds—yet despite a swell of interest coinciding with the composer’s centennial last year, his scores are all too rarely heard. He was always something of an outsider, this unrepentant free spirit and individualist. Harrison studied with Arnold Schoenberg in the 1940s, when the 12-tone master was ensconced in Los Angeles, and gave serial techniques a serious go, but his best music—lyrical, melodic, indebted to the sounds of Southeast Asia—inhabits a different world from so much of the postmodern avant-garde.

The mesmeric work of Lou Harrison (1917–2003) stands apart from so much of the music written in 20th-century America—so singular is its idiom, so striking are its borderless, cross-cultural sounds—yet despite a swell of interest coinciding with the composer’s centennial last year, his scores are all too rarely heard. He was always something of an outsider, this unrepentant free spirit and individualist. Harrison studied with Arnold Schoenberg in the 1940s, when the 12-tone master was ensconced in Los Angeles, and gave serial techniques a serious go, but his best music—lyrical, melodic, indebted to the sounds of Southeast Asia—inhabits a different world from so much of the postmodern avant-garde. You’ve heard the argument before: Genes are the permanent aristocracy of evolution, looking after themselves as fleshy hosts come and go. That’s the thesis of a book that, last year, was christened the most influential science book of all time: Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene. But we humans actually generate far more actionable information than is encoded in all of our combined genetic material, and we carry much of it into the future. The data outside of our biological selves—call it the dataome—could actually represent the grander scaffolding for complex life. The dataome may provide a universally recognizable signature of the slippery characteristic we call intelligence, and it might even teach us a thing or two about ourselves. It is also something that has a considerable energetic burden. That burden challenges us to ask if we are manufacturing and protecting our dataome for our benefit alone, or, like the selfish gene, because the data makes us do this because that’s what ensures its propagation into the future. Take, for instance, William Shakespeare.

You’ve heard the argument before: Genes are the permanent aristocracy of evolution, looking after themselves as fleshy hosts come and go. That’s the thesis of a book that, last year, was christened the most influential science book of all time: Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene. But we humans actually generate far more actionable information than is encoded in all of our combined genetic material, and we carry much of it into the future. The data outside of our biological selves—call it the dataome—could actually represent the grander scaffolding for complex life. The dataome may provide a universally recognizable signature of the slippery characteristic we call intelligence, and it might even teach us a thing or two about ourselves. It is also something that has a considerable energetic burden. That burden challenges us to ask if we are manufacturing and protecting our dataome for our benefit alone, or, like the selfish gene, because the data makes us do this because that’s what ensures its propagation into the future. Take, for instance, William Shakespeare.