Robert Epstein in Global Research:

No matter how hard they try, brain scientists and cognitive psychologists will never find a copy of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony in the brain – or copies of words, pictures, grammatical rules or any other kinds of environmental stimuli. The human brain isn’t really empty, of course. But it does not contain most of the things people think it does – not even simple things such as ‘memories’.

No matter how hard they try, brain scientists and cognitive psychologists will never find a copy of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony in the brain – or copies of words, pictures, grammatical rules or any other kinds of environmental stimuli. The human brain isn’t really empty, of course. But it does not contain most of the things people think it does – not even simple things such as ‘memories’.

Our shoddy thinking about the brain has deep historical roots, but the invention of computers in the 1940s got us especially confused. For more than half a century now, psychologists, linguists, neuroscientists and other experts on human behaviour have been asserting that the human brain works like a computer. To see how vacuous this idea is, consider the brains of babies. Thanks to evolution, human neonates, like the newborns of all other mammalian species, enter the world prepared to interact with it effectively. A baby’s vision is blurry, but it pays special attention to faces, and is quickly able to identify its mother’s. It prefers the sound of voices to non-speech sounds, and can distinguish one basic speech sound from another. We are, without doubt, built to make social connections. A healthy newborn is also equipped with more than a dozen reflexes – ready-made reactions to certain stimuli that are important for its survival. It turns its head in the direction of something that brushes its cheek and then sucks whatever enters its mouth. It holds its breath when submerged in water. It grasps things placed in its hands so strongly it can nearly support its own weight. Perhaps most important, newborns come equipped with powerful learning mechanisms that allow them to change rapidly so they can interact increasingly effectively with their world, even if that world is unlike the one their distant ancestors faced.

Senses, reflexes and learning mechanisms – this is what we start with, and it is quite a lot, when you think about it. If we lacked any of these capabilities at birth, we would probably have trouble surviving.

But here is what we are not born with: information, data, rules, software, knowledge, lexicons, representations, algorithms, programs, models, memories, images, processors, subroutines, encoders, decoders, symbols, or buffers – design elements that allow digital computers to behave somewhat intelligently. Not only are we not born with such things, we also don’t develop them – ever.

We don’t store words or the rules that tell us how to manipulate them. We don’t create representationsof visual stimuli, store them in a short-term memory buffer, and then transfer the representation into a long-term memory device. We don’t retrieve information or images or words from memory registers. Computers do all of these things, but organisms do not. Computers, quite literally, process information – numbers, letters, words, formulas, images. The information first has to be encoded into a format computers can use, which means patterns of ones and zeroes (‘bits’) organised into small chunks (‘bytes’). On my computer, each byte contains 8 bits, and a certain pattern of those bits stands for the letter d, another for the letter o, and another for the letter g. Side by side, those three bytes form the word dog. One single image – say, the photograph of my cat Henry on my desktop – is represented by a very specific pattern of a million of these bytes (‘one megabyte’), surrounded by some special characters that tell the computer to expect an image, not a word.

More here.

When I suggest a nexus between style and morality I mean always to keep the query centered on the book, to interrogate the book’s moral vision as it is activated in language. That vision, like everything else in the writer’s arsenal, is manifest in style. Language is our fullest, most accurate embodiment of mind. How you write is how you think, and there’s reciprocity there, a fertile feedback loop, because the writing in turn sharpens the thinking, which in turn sharpens the writing. This is what Goethe means by “a writer’s style is a true reflection of his inner life.” Remember, too, Nabokov’s oft-cited line: “Style is matter.” He means that style is not something gummed onto prose after the fact—style is the fact. Style is born of subject. Robert Penn Warren makes a similar observation: “The style of a writer represents his stance toward experience.” That’s what Auden means in his second consideration above.

When I suggest a nexus between style and morality I mean always to keep the query centered on the book, to interrogate the book’s moral vision as it is activated in language. That vision, like everything else in the writer’s arsenal, is manifest in style. Language is our fullest, most accurate embodiment of mind. How you write is how you think, and there’s reciprocity there, a fertile feedback loop, because the writing in turn sharpens the thinking, which in turn sharpens the writing. This is what Goethe means by “a writer’s style is a true reflection of his inner life.” Remember, too, Nabokov’s oft-cited line: “Style is matter.” He means that style is not something gummed onto prose after the fact—style is the fact. Style is born of subject. Robert Penn Warren makes a similar observation: “The style of a writer represents his stance toward experience.” That’s what Auden means in his second consideration above.

The French people are constantly hauled on to a Corneille-like stage with and by de Gaulle, two characters in search of a destiny, with soliloquies, debates, monologues, conducted in newspapers, radio and television although, such is the nature of a biography, “the people” are really the audience that listens and is moulded, enchanted or aroused to sublimity by the suasion of that resonant, nasal, rhythmic voice. As was noticed on several occasions, de Gaulle was a traditional Catholic Christian; he rarely spoke of or even mentioned God but rarely failed to speak instead of France, the great stained-glass rose window in which the divine light had glowed through the centuries in radiance or in sombre melancholy, picking out at irregular intervals the ranged silhouettes of a Clovis, a Charlemagne, an Henri IV, a Joan of Arc, Louis XI, a Colbert, Richelieu, Louis XIV (or his great general Louvois), a Napoleon and, at last, a de Gaulle. Régis Debray in 1990 is quoted: “In my dreams I am on terms of easy familiarity with Louis XI, with Lenin, with Edison and Lincoln. But I quail before de Gaulle. He is the Great Other, the inaccessible absolute … Napoleon was the great political myth of the nineteenth century; de Gaulle of the twentieth. The sublime, it seems, appears in France only once a century.” Debray had once regarded Mitterrand as a saviour ‑ rather hard to believe now in any retrospective light ‑ but this literary-political canonisation would have pleased de Gaulle, for he certainly believed it to be true, true as only a myth can be.

The French people are constantly hauled on to a Corneille-like stage with and by de Gaulle, two characters in search of a destiny, with soliloquies, debates, monologues, conducted in newspapers, radio and television although, such is the nature of a biography, “the people” are really the audience that listens and is moulded, enchanted or aroused to sublimity by the suasion of that resonant, nasal, rhythmic voice. As was noticed on several occasions, de Gaulle was a traditional Catholic Christian; he rarely spoke of or even mentioned God but rarely failed to speak instead of France, the great stained-glass rose window in which the divine light had glowed through the centuries in radiance or in sombre melancholy, picking out at irregular intervals the ranged silhouettes of a Clovis, a Charlemagne, an Henri IV, a Joan of Arc, Louis XI, a Colbert, Richelieu, Louis XIV (or his great general Louvois), a Napoleon and, at last, a de Gaulle. Régis Debray in 1990 is quoted: “In my dreams I am on terms of easy familiarity with Louis XI, with Lenin, with Edison and Lincoln. But I quail before de Gaulle. He is the Great Other, the inaccessible absolute … Napoleon was the great political myth of the nineteenth century; de Gaulle of the twentieth. The sublime, it seems, appears in France only once a century.” Debray had once regarded Mitterrand as a saviour ‑ rather hard to believe now in any retrospective light ‑ but this literary-political canonisation would have pleased de Gaulle, for he certainly believed it to be true, true as only a myth can be. Douglass’s current status as a national hero poses a challenge for the biographer, making it difficult to view him dispassionately. Moreover, those who seek to tell his story must compete with their subject’s own version of it. Douglass published three autobiographies, among the greatest works of this genre in American literature. They present not only a powerful indictment of slavery, but also a tale of extraordinary individual achievement (it is no accident that Douglass’s most frequently delivered lecture was titled “Self-Made Men”). Like all autobiographies, however, Douglass’s were simultaneously historical narratives and works of the imagination. As David Blight notes in his new book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, some passages in them—especially those relating to Douglass’s childhood—are “almost pure invention,” which means the biographer must resist the temptation to take these books entirely at face value.

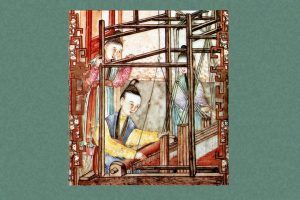

Douglass’s current status as a national hero poses a challenge for the biographer, making it difficult to view him dispassionately. Moreover, those who seek to tell his story must compete with their subject’s own version of it. Douglass published three autobiographies, among the greatest works of this genre in American literature. They present not only a powerful indictment of slavery, but also a tale of extraordinary individual achievement (it is no accident that Douglass’s most frequently delivered lecture was titled “Self-Made Men”). Like all autobiographies, however, Douglass’s were simultaneously historical narratives and works of the imagination. As David Blight notes in his new book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, some passages in them—especially those relating to Douglass’s childhood—are “almost pure invention,” which means the biographer must resist the temptation to take these books entirely at face value. The cultural association between women and the manufacture of textiles runs deep. Many of the deities associated with spinning and weaving are female: Neith in pre-Dynastic Egypt; Grecian Athena; the Norse goddess Frigg and the Chinese Silkworm Goddess. Skill with needle, thread or a loom was seen in many cultures as an intrinsic part of a woman’s value. In Greece, the birth of a baby girl was sometimes marked by placing a tuft of wool by the door of a home. And Homer wrote that when his countrymen raided towns and villages they killed the men they encountered, but women were spared in order to spin and weave in captivity. The “distaff side” was a traditional English term for the maternal side of a family. Women the world over were buried with spindles and distaffs, the very tools they wielded so dexterously and for so many hours in life. Sarah Arderne, a member of the lesser gentry in northern England in the late eighteenth century, bought muslin for her husband’s cravats and handkerchief and supervised the laundering of all his linens. She was pretty typical: it wasn’t unusual for men of this class and period to live and die without ever taking responsibility for their own shirts.

The cultural association between women and the manufacture of textiles runs deep. Many of the deities associated with spinning and weaving are female: Neith in pre-Dynastic Egypt; Grecian Athena; the Norse goddess Frigg and the Chinese Silkworm Goddess. Skill with needle, thread or a loom was seen in many cultures as an intrinsic part of a woman’s value. In Greece, the birth of a baby girl was sometimes marked by placing a tuft of wool by the door of a home. And Homer wrote that when his countrymen raided towns and villages they killed the men they encountered, but women were spared in order to spin and weave in captivity. The “distaff side” was a traditional English term for the maternal side of a family. Women the world over were buried with spindles and distaffs, the very tools they wielded so dexterously and for so many hours in life. Sarah Arderne, a member of the lesser gentry in northern England in the late eighteenth century, bought muslin for her husband’s cravats and handkerchief and supervised the laundering of all his linens. She was pretty typical: it wasn’t unusual for men of this class and period to live and die without ever taking responsibility for their own shirts. Simone Weil (1909-43) belonged to a species so rare, it had only one member. This peculiar French philosopher and mystic diagnosed the maladies and maledictions of her own age and place – Europe in the first war-torn half of the 20th century – and offered recommendations for how to forestall the repetition of its iniquities: totalitarianism, income inequality, restriction of free speech, political polarisation, the alienation of the modern subject, and more. Her combination of erudition, political and spiritual fervour, and commitment to her ideals adds weight to the distinctive diagnosis she offers of modernity. Weil has been dead now for 75 years but remains able to tell us much about ourselves. Born to a secular Jewish family in Paris, she was gifted from the beginning with a thirst for knowledge of other cultures and her own. Fluent in Ancient Greek by the age of 12, she taught herself Sanskrit, and took an interest in Hinduism and Buddhism. She excelled at the Lycée Henri IV and the École normale supérieure, where she studied philosophy. Plato was a lasting influence, and her interest in political philosophy led her to Karl Marx, whose thought she esteemed but did not blindly assimilate.

Simone Weil (1909-43) belonged to a species so rare, it had only one member. This peculiar French philosopher and mystic diagnosed the maladies and maledictions of her own age and place – Europe in the first war-torn half of the 20th century – and offered recommendations for how to forestall the repetition of its iniquities: totalitarianism, income inequality, restriction of free speech, political polarisation, the alienation of the modern subject, and more. Her combination of erudition, political and spiritual fervour, and commitment to her ideals adds weight to the distinctive diagnosis she offers of modernity. Weil has been dead now for 75 years but remains able to tell us much about ourselves. Born to a secular Jewish family in Paris, she was gifted from the beginning with a thirst for knowledge of other cultures and her own. Fluent in Ancient Greek by the age of 12, she taught herself Sanskrit, and took an interest in Hinduism and Buddhism. She excelled at the Lycée Henri IV and the École normale supérieure, where she studied philosophy. Plato was a lasting influence, and her interest in political philosophy led her to Karl Marx, whose thought she esteemed but did not blindly assimilate. When something in the body goes wrong, we see a doctor, get examined, get swabbed or draw blood, and usually leave with an answer. But for many patients and families, medical examination doesn’t lead to a diagnosis—and what do they do then? A paper

When something in the body goes wrong, we see a doctor, get examined, get swabbed or draw blood, and usually leave with an answer. But for many patients and families, medical examination doesn’t lead to a diagnosis—and what do they do then? A paper  No matter how hard they try, brain scientists and cognitive psychologists will never find a copy of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony in the brain – or copies of words, pictures, grammatical rules or any other kinds of environmental stimuli. The human brain isn’t really empty, of course. But it does not contain most of the things people think it does – not even simple things such as ‘memories’.

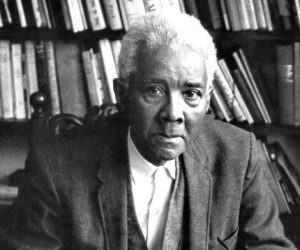

No matter how hard they try, brain scientists and cognitive psychologists will never find a copy of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony in the brain – or copies of words, pictures, grammatical rules or any other kinds of environmental stimuli. The human brain isn’t really empty, of course. But it does not contain most of the things people think it does – not even simple things such as ‘memories’. “I denounce European colonialism”, wrote CLR James in 1980, “but I respect the learning and profound discoveries of Western civilisation.” A Marxist revolutionary and Pan-Africanist, a historian and novelist, an icon of black liberation and die-hard cricket fan, a classicist and lover of popular culture, Cyril Lionel Roberts James, described by V.S Naipaul as “the master of all topics”, was one of the great (yet grossly underrated) intellectuals of the 20th century.

“I denounce European colonialism”, wrote CLR James in 1980, “but I respect the learning and profound discoveries of Western civilisation.” A Marxist revolutionary and Pan-Africanist, a historian and novelist, an icon of black liberation and die-hard cricket fan, a classicist and lover of popular culture, Cyril Lionel Roberts James, described by V.S Naipaul as “the master of all topics”, was one of the great (yet grossly underrated) intellectuals of the 20th century. The woman sitting next to me in the waiting room is wearing a blue dashiki, a sterile paper face mask to protect her from infection, and a black leather Oakland Raiders baseball cap. I look down at her brown, sandaled feet and see that her toenails are the color of green papaya, glossy and enameled.

The woman sitting next to me in the waiting room is wearing a blue dashiki, a sterile paper face mask to protect her from infection, and a black leather Oakland Raiders baseball cap. I look down at her brown, sandaled feet and see that her toenails are the color of green papaya, glossy and enameled. Often, in the study of past human and natural processes, the realisation that we have no evidence of something, and therefore no positive knowledge, transforms too quickly into the conclusion that because we have no positive knowledge, we may therefore assume the negative. Sometimes this conclusion is correct, but it cannot be applied indiscriminately. To cite one interesting example of the correct and useful refusal to apply it, in recent probabilistic reasoning about extraterrestrials the absence of any direct evidence for their existence is taken as irrelevant to whether we should believe in them or not. Drake’s equation is more powerful than radio signals or space ships in shaping our beliefs.

Often, in the study of past human and natural processes, the realisation that we have no evidence of something, and therefore no positive knowledge, transforms too quickly into the conclusion that because we have no positive knowledge, we may therefore assume the negative. Sometimes this conclusion is correct, but it cannot be applied indiscriminately. To cite one interesting example of the correct and useful refusal to apply it, in recent probabilistic reasoning about extraterrestrials the absence of any direct evidence for their existence is taken as irrelevant to whether we should believe in them or not. Drake’s equation is more powerful than radio signals or space ships in shaping our beliefs. A few years ago, a senior Japanese central banker let me in on a secret side of his life: Like some others in his rarefied world, he is a passionate devotee of Sherlock Holmes. After formal meetings in capitals around the world, he joins the other Sherlock Holmes buffs over drinks or dinner for trivia competitions, to test their knowledge of obscure plot details, or to share amateur historical research into Victorian London.

A few years ago, a senior Japanese central banker let me in on a secret side of his life: Like some others in his rarefied world, he is a passionate devotee of Sherlock Holmes. After formal meetings in capitals around the world, he joins the other Sherlock Holmes buffs over drinks or dinner for trivia competitions, to test their knowledge of obscure plot details, or to share amateur historical research into Victorian London. It may strike a reader new to George Scialabba’s writing as extraordinary that

It may strike a reader new to George Scialabba’s writing as extraordinary that  Every time Jim meets a patient, he cries,” Padmanee said to The New York Times in 2016. “Well not every time,” Jim added. Jim Allison and Padmanee Sharma work together at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, having met in 2005 and married in 2014. A decade before they met, Allison and his lab team made a seminal discovery that led to a revolution in cancer medicine. The hype is deserved; cancer physicians agree that Allison’s idea is a game-changer, and it now sits alongside surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy as a mainstream option for the treatment of some types of cancer.

Every time Jim meets a patient, he cries,” Padmanee said to The New York Times in 2016. “Well not every time,” Jim added. Jim Allison and Padmanee Sharma work together at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, having met in 2005 and married in 2014. A decade before they met, Allison and his lab team made a seminal discovery that led to a revolution in cancer medicine. The hype is deserved; cancer physicians agree that Allison’s idea is a game-changer, and it now sits alongside surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy as a mainstream option for the treatment of some types of cancer. Just a few weeks before her death in October, Mary Midgley agreed to meet and discuss her new book, What Is Philosophy For? It seemed astonishing that someone about to celebrate her 99th birthday had a new book out, but I was less in awe of that than the reputation of one of the most important British philosophers of the 20th century and beyond.

Just a few weeks before her death in October, Mary Midgley agreed to meet and discuss her new book, What Is Philosophy For? It seemed astonishing that someone about to celebrate her 99th birthday had a new book out, but I was less in awe of that than the reputation of one of the most important British philosophers of the 20th century and beyond. In 2016, a series of unassuming stone shapes rocked the paleobiology world when they were

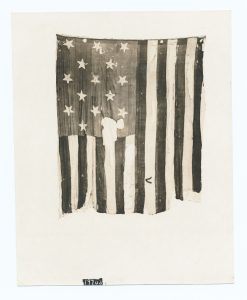

In 2016, a series of unassuming stone shapes rocked the paleobiology world when they were  What was America? The question is nearly as old as the republic itself. In 1789, the year George Washington began his first term, the South Carolina doctor and statesman David Ramsay set out to understand the new nation by looking to its short past. America’s histories at the time were local, stories of states or scattered tales of colonial lore; nations were tied together by bloodline, or religion, or ancestral soil. “The Americans knew but little of one another,” Ramsay wrote, delivering an accounting that both presented his contemporaries as a single people, despite their differences, and tossed aside the assumptions of what would be needed to hold them together. “When the war began, the Americans were a mass of husbandmen, merchants, mechanics and fishermen; but the necessities of the country gave a spring to the active powers of the inhabitants, and set them on thinking, speaking and acting in a line far beyond that to which they had been accustomed.” The Constitution had just been ratified at the time of Ramsay’s writing, the first system of national government submitted to its people for approval. “A vast expansion of the human mind speedily followed,” he wrote. It hashed out the nation as a set of principles. America was an idea. America was an argument.

What was America? The question is nearly as old as the republic itself. In 1789, the year George Washington began his first term, the South Carolina doctor and statesman David Ramsay set out to understand the new nation by looking to its short past. America’s histories at the time were local, stories of states or scattered tales of colonial lore; nations were tied together by bloodline, or religion, or ancestral soil. “The Americans knew but little of one another,” Ramsay wrote, delivering an accounting that both presented his contemporaries as a single people, despite their differences, and tossed aside the assumptions of what would be needed to hold them together. “When the war began, the Americans were a mass of husbandmen, merchants, mechanics and fishermen; but the necessities of the country gave a spring to the active powers of the inhabitants, and set them on thinking, speaking and acting in a line far beyond that to which they had been accustomed.” The Constitution had just been ratified at the time of Ramsay’s writing, the first system of national government submitted to its people for approval. “A vast expansion of the human mind speedily followed,” he wrote. It hashed out the nation as a set of principles. America was an idea. America was an argument. IN A 1985 INTERVIEW, Anni Albers remarked, “I find that, when the work is made with threads, it’s considered a craft; when it’s on paper, it’s considered art.” This was her somewhat oblique explanation of why she hadn’t received “the longed-for pat on the shoulder,” i.e., recognition as an artist, until after she gave up weaving and immersed herself in printmaking—a transition that occurred when she was in her sixties. It’s hard to judge whether Albers’s tone was wry or rueful or (as one critic alleged) “some-what bitter,” and therefore it’s unclear what her comment might indicate about the belatedness of this acknowledgment relative to her own sense of her achievement. After all, she had been making “pictorial weavings”—textiles designed expressly as art—since the late 1940s. Though the question might now seem moot, it isn’t, given the enduring debates about the hierarchical distinctions that separate fine art from craft, and given the still contested status of self-identified fiber artists who followed in Albers’s footsteps and claimed their woven forms as fine art, tout court.

IN A 1985 INTERVIEW, Anni Albers remarked, “I find that, when the work is made with threads, it’s considered a craft; when it’s on paper, it’s considered art.” This was her somewhat oblique explanation of why she hadn’t received “the longed-for pat on the shoulder,” i.e., recognition as an artist, until after she gave up weaving and immersed herself in printmaking—a transition that occurred when she was in her sixties. It’s hard to judge whether Albers’s tone was wry or rueful or (as one critic alleged) “some-what bitter,” and therefore it’s unclear what her comment might indicate about the belatedness of this acknowledgment relative to her own sense of her achievement. After all, she had been making “pictorial weavings”—textiles designed expressly as art—since the late 1940s. Though the question might now seem moot, it isn’t, given the enduring debates about the hierarchical distinctions that separate fine art from craft, and given the still contested status of self-identified fiber artists who followed in Albers’s footsteps and claimed their woven forms as fine art, tout court.