Nick Pinkerton at Artforum:

GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX is an encyclopedia of ways in which the human body can bend and break, a sailor’s knot guide of the contortions possible with four limbs, a trunk, and a head, skulls seemingly empty here of thoughts other than sex and death. Set in an isolated school somewhere outside of Paris where a troupe of hip-hop dancers have assembled for intensive rehearsals before an impending American tour, the movie unravels in something like real-time as, cutting loose at the end of a day’s work, they dip into a punchbowl of sangria before discovering that one of their group has spiked it with LSD, precipitating a collective freak-out.

GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX is an encyclopedia of ways in which the human body can bend and break, a sailor’s knot guide of the contortions possible with four limbs, a trunk, and a head, skulls seemingly empty here of thoughts other than sex and death. Set in an isolated school somewhere outside of Paris where a troupe of hip-hop dancers have assembled for intensive rehearsals before an impending American tour, the movie unravels in something like real-time as, cutting loose at the end of a day’s work, they dip into a punchbowl of sangria before discovering that one of their group has spiked it with LSD, precipitating a collective freak-out.

The film opens with a premonition of catastrophe: an indifferent-God’s-eye-view of a bloodied young woman wading through a field of snow before collapsing and flailingly tracing an angel in the powder.

more here.

High in the mountains of Central America lives a little known creature called Alston’s singing mouse. This rodent, which spends its life scuttling around the floor of the cloud forest, may not seem like it has much to tell us about ourselves. But the mouse produces remarkable songs, and researchers

High in the mountains of Central America lives a little known creature called Alston’s singing mouse. This rodent, which spends its life scuttling around the floor of the cloud forest, may not seem like it has much to tell us about ourselves. But the mouse produces remarkable songs, and researchers  The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.

The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.

Just about everyone who visits the famous

Just about everyone who visits the famous

My seventy-something year old uncle, who still uses a flip phone, was talking to me a while ago about self-driving cars. He was adamant that he didn’t want to put his fate in the hands of a computer, he didn’t trust them. My question to him was “but you trust other people in cars?” Because self-driving cars don’t have to be 100% accurate, they just have to be better than people, and they already are. People get drunk, they get tired, they’re distracted, they’re looking down at their phones. Computers won’t do any of those things. And yet my uncle couldn’t be persuaded. He fundamentally doesn’t trust computers. And of course, he’s not alone. More and more of our lives have highly automated elements to them,

My seventy-something year old uncle, who still uses a flip phone, was talking to me a while ago about self-driving cars. He was adamant that he didn’t want to put his fate in the hands of a computer, he didn’t trust them. My question to him was “but you trust other people in cars?” Because self-driving cars don’t have to be 100% accurate, they just have to be better than people, and they already are. People get drunk, they get tired, they’re distracted, they’re looking down at their phones. Computers won’t do any of those things. And yet my uncle couldn’t be persuaded. He fundamentally doesn’t trust computers. And of course, he’s not alone. More and more of our lives have highly automated elements to them,  The Anna Karenina Fix

The Anna Karenina Fix In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative.

In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative. Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?  Soon after I arrive in Chicago, on an August afternoon with a heat I remember from childhood, I head to a bar on the North Side and shoot pool. I haven’t been to this city in more than a year, because going home isn’t easy. But I’ve been called back for the wedding of a close friend, which will take place later in the weekend. My friend, the groom—let’s call him X.— is a journalist, and many of the other attendees are people like me, journalists or writers.

Soon after I arrive in Chicago, on an August afternoon with a heat I remember from childhood, I head to a bar on the North Side and shoot pool. I haven’t been to this city in more than a year, because going home isn’t easy. But I’ve been called back for the wedding of a close friend, which will take place later in the weekend. My friend, the groom—let’s call him X.— is a journalist, and many of the other attendees are people like me, journalists or writers. The tiny village of Lasserre is tucked into one of France’s southernmost hills, a hamlet of stone buildings strong in the embrace of centuries-old cement. The home in which the mathematician Alexander Grothendieck spent the last two decades of his life in near-complete seclusion is as tranquil as its neighbors. A patchwork of vines—trained, then abandoned—climb toward the white shutters and terracotta roof. Among the few postwar sentries is a standard-issue metal mailbox. Visitors left mostly unclaimed notes for him; letters via post were marked retour a l’envoyeur. The locals knew to leave him alone, but when a young mathematician arrived in the early 1990s in hopes of speaking to him, he slammed the door in her face, screaming.

The tiny village of Lasserre is tucked into one of France’s southernmost hills, a hamlet of stone buildings strong in the embrace of centuries-old cement. The home in which the mathematician Alexander Grothendieck spent the last two decades of his life in near-complete seclusion is as tranquil as its neighbors. A patchwork of vines—trained, then abandoned—climb toward the white shutters and terracotta roof. Among the few postwar sentries is a standard-issue metal mailbox. Visitors left mostly unclaimed notes for him; letters via post were marked retour a l’envoyeur. The locals knew to leave him alone, but when a young mathematician arrived in the early 1990s in hopes of speaking to him, he slammed the door in her face, screaming. The first Israeli mission to the moon carried a secret cargo, a small metal disk that contains the building blocks of human civilization in 30 million pages of information.

The first Israeli mission to the moon carried a secret cargo, a small metal disk that contains the building blocks of human civilization in 30 million pages of information. IF SOMEONE WERE TO MAKE

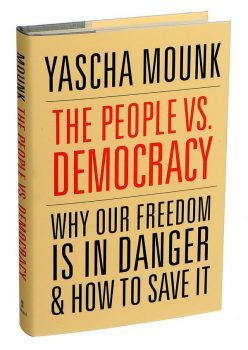

IF SOMEONE WERE TO MAKE There was once a liberal dream: “A free society of equals, based on the proliferation of opportunities for individuals to lead lives characterized by personal independence from the domination of others,” as Elizabeth Anderson writes of the Levellers during the English Civil War. In Yascha Mounk’s The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It, the liberal dream, limited as it might have been, has noticeably narrowed.

There was once a liberal dream: “A free society of equals, based on the proliferation of opportunities for individuals to lead lives characterized by personal independence from the domination of others,” as Elizabeth Anderson writes of the Levellers during the English Civil War. In Yascha Mounk’s The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It, the liberal dream, limited as it might have been, has noticeably narrowed. ‘The whole aim of practical politics,’ wrote H.L. Mencken, ‘is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.’ Newspapers, politicians and pressure groups have been moving smoothly for decades from one forecast apocalypse to another (nuclear power, acid rain, the ozone layer, mad cow disease, nanotechnology, genetically modified crops, the millennium bug…) without waiting to be proved right or wrong.

‘The whole aim of practical politics,’ wrote H.L. Mencken, ‘is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.’ Newspapers, politicians and pressure groups have been moving smoothly for decades from one forecast apocalypse to another (nuclear power, acid rain, the ozone layer, mad cow disease, nanotechnology, genetically modified crops, the millennium bug…) without waiting to be proved right or wrong.