Ian Dreiblatt at The Believer:

Cheesemania ’93, as I’ve decided to call it, is a classic TV commercial. In a civilization organized primarily around the funneling of capital to corporations, commercials offer a space of transcendent communion with the objects of our dependence and desire. They take place in a realm understood to be ideational without quite being imaginary—existing not in any one person’s mind, but ambiently, on a level of reality we rarely think to question, encoded in the daily order of things as neatly as the peanut butter aisle of a suburban grocery store. (This bare proximity to capitalism’s exposed nerves, combined with a habitual callousness to human dignity, is I believe why, in the recent words of A.S. Hamrah, “TV commercials are the worst thing to see on hallucinogenic drugs.”) These commercials embody and transmit all kinds of cultural norms, declaiming on the career-destroying horror of “even one flake” of dandruff, the correct way to manage a labor force, how women should interpret cough syrup viscosity, and so on.

Cheesemania ’93, as I’ve decided to call it, is a classic TV commercial. In a civilization organized primarily around the funneling of capital to corporations, commercials offer a space of transcendent communion with the objects of our dependence and desire. They take place in a realm understood to be ideational without quite being imaginary—existing not in any one person’s mind, but ambiently, on a level of reality we rarely think to question, encoded in the daily order of things as neatly as the peanut butter aisle of a suburban grocery store. (This bare proximity to capitalism’s exposed nerves, combined with a habitual callousness to human dignity, is I believe why, in the recent words of A.S. Hamrah, “TV commercials are the worst thing to see on hallucinogenic drugs.”) These commercials embody and transmit all kinds of cultural norms, declaiming on the career-destroying horror of “even one flake” of dandruff, the correct way to manage a labor force, how women should interpret cough syrup viscosity, and so on.

more here.

Fiona MacCarthy met Walter Gropius (1883–1969) through Jack Pritchard, the British entrepreneur who built Lawn Road Flats in Hampstead, an experiment in modernist living where Gropius took up residence after escaping Nazi Germany in 1934. The Bauhaus, the school he founded in Weimar a century ago this year, had been closed by stormtroopers the previous year (by then it had moved to Berlin). In 1968, after the opening of a Bauhaus exhibition at the Royal Academy, MacCarthy was invited to dinner with Gropius at the Lawn Road Isobar, the block’s in-house dining room: ‘He was then eighty-five, small, upright, very courteous, retaining a Germanic formality of bearing,’ MacCarthy recalled. He ‘was still valiant and impressive, with a flickering of arrogance’.

Fiona MacCarthy met Walter Gropius (1883–1969) through Jack Pritchard, the British entrepreneur who built Lawn Road Flats in Hampstead, an experiment in modernist living where Gropius took up residence after escaping Nazi Germany in 1934. The Bauhaus, the school he founded in Weimar a century ago this year, had been closed by stormtroopers the previous year (by then it had moved to Berlin). In 1968, after the opening of a Bauhaus exhibition at the Royal Academy, MacCarthy was invited to dinner with Gropius at the Lawn Road Isobar, the block’s in-house dining room: ‘He was then eighty-five, small, upright, very courteous, retaining a Germanic formality of bearing,’ MacCarthy recalled. He ‘was still valiant and impressive, with a flickering of arrogance’.

Variations of the genome editor CRISPR have wowed biology labs around the world over the past few years because they can precisely change single DNA bases, promising deft repairs for genetic diseases and improvements in crop and livestock genomes. But such “base editors” can have a serious weakness. A pair of studies published online in Science this week

Variations of the genome editor CRISPR have wowed biology labs around the world over the past few years because they can precisely change single DNA bases, promising deft repairs for genetic diseases and improvements in crop and livestock genomes. But such “base editors” can have a serious weakness. A pair of studies published online in Science this week  During six years of singlehood in my 20s, I became a person I did not know. Before, I had always been a reader. I walked to the library several times a week as a kid and stayed up late into the night reading under my blankets with a flashlight. I checked out so many books and returned them so quickly the librarian once snapped, “Don’t take home so many books if you’re not going to read them all.”

During six years of singlehood in my 20s, I became a person I did not know. Before, I had always been a reader. I walked to the library several times a week as a kid and stayed up late into the night reading under my blankets with a flashlight. I checked out so many books and returned them so quickly the librarian once snapped, “Don’t take home so many books if you’re not going to read them all.” Quassim Cassam

Quassim Cassam You probably already know—or think you know—what happened on the night of September 25, 2017 between Aziz Ansari and an anonymous woman calling herself “Grace.” These are the accepted facts: she went on a date with Ansari, they went back to his house, and then had some sexual contact that left Grace feeling deeply uncomfortable. No crime was alleged, since Ansari did not force himself on Grace in any way, but this was clearly a nasty encounter for her. The next day, she texted Ansari telling him as much and he apologized for having “misread things.” Several months later, she published her

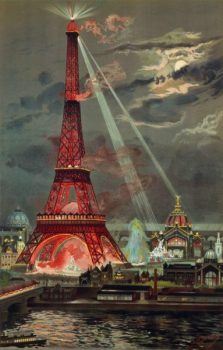

You probably already know—or think you know—what happened on the night of September 25, 2017 between Aziz Ansari and an anonymous woman calling herself “Grace.” These are the accepted facts: she went on a date with Ansari, they went back to his house, and then had some sexual contact that left Grace feeling deeply uncomfortable. No crime was alleged, since Ansari did not force himself on Grace in any way, but this was clearly a nasty encounter for her. The next day, she texted Ansari telling him as much and he apologized for having “misread things.” Several months later, she published her  When the Eiffel Tower—the daring centerpiece of the centenary celebration of the French Revolution, the 1889 Exposition Universelle—was new, it was widely disparaged for its impertinent mechanical appearance. The distinctive 300-meter iron structure still looms over western Paris from the Champ de Mars close to the Seine, but it is now admired, even adored. The history of the Tower thus contains a two-fold surprise: it was the odd World’s Fair edifice to survive, and, though once reviled, it is now loved. Not only has the old derrick-shaped monument become endearing, its thrusting gigantism, surprising shape, and unapologetically industrial materials, along with its attention-grabbing nocturnal lighting and mesmerizing daytime transparency, make it inescapable in many districts of the French capital city. And not only there: owing to its nonstop reproduction and circulation, its familiarity exceeds the spaces of Paris. On account of its global popularity, it is called an urban icon. According to leading image historians, the Tower is “a reference-point for urban signification,” “the iconic object of Paris,” and “the archetype for all urban icons to follow.” The parent of this outlook was literary critic Roland Barthes. In 1964, he argued influentially that the bases of the Tower’s clout are its widespread fame and its emptiness: it is both “a pure signifier” and “an utterly useless monument” meaning that wherever the Tower is known, it absorbs any claim whatsoever about its identity and significance.

When the Eiffel Tower—the daring centerpiece of the centenary celebration of the French Revolution, the 1889 Exposition Universelle—was new, it was widely disparaged for its impertinent mechanical appearance. The distinctive 300-meter iron structure still looms over western Paris from the Champ de Mars close to the Seine, but it is now admired, even adored. The history of the Tower thus contains a two-fold surprise: it was the odd World’s Fair edifice to survive, and, though once reviled, it is now loved. Not only has the old derrick-shaped monument become endearing, its thrusting gigantism, surprising shape, and unapologetically industrial materials, along with its attention-grabbing nocturnal lighting and mesmerizing daytime transparency, make it inescapable in many districts of the French capital city. And not only there: owing to its nonstop reproduction and circulation, its familiarity exceeds the spaces of Paris. On account of its global popularity, it is called an urban icon. According to leading image historians, the Tower is “a reference-point for urban signification,” “the iconic object of Paris,” and “the archetype for all urban icons to follow.” The parent of this outlook was literary critic Roland Barthes. In 1964, he argued influentially that the bases of the Tower’s clout are its widespread fame and its emptiness: it is both “a pure signifier” and “an utterly useless monument” meaning that wherever the Tower is known, it absorbs any claim whatsoever about its identity and significance. A writer of enormous energy, Burgess suffered from an embarrassment of riches as well as from an excessive love of words and language. The vulgar and irritating phrase “swallowed the dictionary” could have been coined for him, and he cheerfully recommends “ransacking the dictionary” when in need of an inspirational boost. Rejecting a critic who praised Shakespeare’s dying delirium in his novel Nothing Like the Sun (1964) as “writing of the highest order”, he confesses, “Not quite so, really. I had taught myself the trick of contriving a satisfactory coda by what, in music, is termed aleatory means: I flicked through a dictionary and took whatever words leaped from the page. I did this again at the end of my Napoleon novel: the effect is surrealistic, oceanic, and easily achieved”. (You’ve Had Your Time, Chapter Two.) This is a very odd mode of composition. Lorna Sage nailed it in a review of Napoleon Symphony (1974), which he quotes in his memoir with what seems to be approval as “probably profound”. Sage writes, “he is original, inventive, idiosyncratic even, and yet the ingredients are synthetic . . . . His own attitude to this, so far as one can extract anything so direct from the novel, is determinedly, manically cheerful. Better the collective unwisdom of the verbal stew, he would say, than any tyrannous signature”. Sage was a brilliantly perceptive critic, and she could read an author’s mind.

A writer of enormous energy, Burgess suffered from an embarrassment of riches as well as from an excessive love of words and language. The vulgar and irritating phrase “swallowed the dictionary” could have been coined for him, and he cheerfully recommends “ransacking the dictionary” when in need of an inspirational boost. Rejecting a critic who praised Shakespeare’s dying delirium in his novel Nothing Like the Sun (1964) as “writing of the highest order”, he confesses, “Not quite so, really. I had taught myself the trick of contriving a satisfactory coda by what, in music, is termed aleatory means: I flicked through a dictionary and took whatever words leaped from the page. I did this again at the end of my Napoleon novel: the effect is surrealistic, oceanic, and easily achieved”. (You’ve Had Your Time, Chapter Two.) This is a very odd mode of composition. Lorna Sage nailed it in a review of Napoleon Symphony (1974), which he quotes in his memoir with what seems to be approval as “probably profound”. Sage writes, “he is original, inventive, idiosyncratic even, and yet the ingredients are synthetic . . . . His own attitude to this, so far as one can extract anything so direct from the novel, is determinedly, manically cheerful. Better the collective unwisdom of the verbal stew, he would say, than any tyrannous signature”. Sage was a brilliantly perceptive critic, and she could read an author’s mind. We can practically feel the wind blowing upon our cheek, so visceral is Thomson’s tone painting here. The sonorities of the orchestra are bright, the musicians strumming phrases like an ancient lyre, the baritone morphing from priest into bard. There’s a lovely decadence to these lyrical passages in duple and triple time, as the singer pleads with Diana to refrain from hunting in her wooded realm so that the party can continue unimpeded. The chaste Diana, meanwhile, has not been invited to the celebration; that her realm is being violated is suggested by another contrasting musical texture—still lyrical but with hints of darkness not far beneath the surface.

We can practically feel the wind blowing upon our cheek, so visceral is Thomson’s tone painting here. The sonorities of the orchestra are bright, the musicians strumming phrases like an ancient lyre, the baritone morphing from priest into bard. There’s a lovely decadence to these lyrical passages in duple and triple time, as the singer pleads with Diana to refrain from hunting in her wooded realm so that the party can continue unimpeded. The chaste Diana, meanwhile, has not been invited to the celebration; that her realm is being violated is suggested by another contrasting musical texture—still lyrical but with hints of darkness not far beneath the surface. What do you think of when you think of a rainbow? If you’re sighted, you’re probably imagining colors arcing through the sky just after the rain. But what about someone who can’t see a rainbow? How does a congenitally blind person’s knowledge of a rainbow—or even something as seemingly simple as the color red—differ from that of the sighted? The answer, Alfonso Caramazza said, is complicated: There are similarities but also important differences.

What do you think of when you think of a rainbow? If you’re sighted, you’re probably imagining colors arcing through the sky just after the rain. But what about someone who can’t see a rainbow? How does a congenitally blind person’s knowledge of a rainbow—or even something as seemingly simple as the color red—differ from that of the sighted? The answer, Alfonso Caramazza said, is complicated: There are similarities but also important differences.

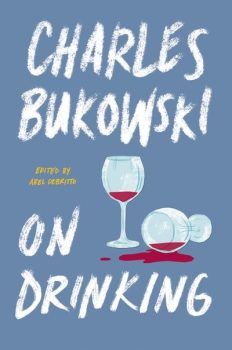

Bukowski relished his image as a swaggering outsider, the kind of man who, having consented to read his poetry at a college, “put down my poems and asked if anybody wanted to arm wrestle.” (Someone did; naturally Bukowski won.) In “On Drinking,” his escapades are entirely typical and roughly as follows: He goes to, copes with or barely avoids jail. He mouths off to cops. He gets into unprovoked fistfights that take three pages to describe and that involve dozens of barehanded punches to the head. He offers to clean a bar’s dirty blinds for money and whiskey, and then, Tom Sawyer-style, persuades the other patrons to do the job for him. He is coated in vomit and/or blood with the regularity of an E.R. nurse. He pleasures, or fails to pleasure, scores of women, none of whom are dissuaded by the foregoing vomit or blood. And he wants nothing to do with modern writers who “lecture at universities / in tie and suit, / the little boys soberly studious, / the little girls with glazed eyes.”

Bukowski relished his image as a swaggering outsider, the kind of man who, having consented to read his poetry at a college, “put down my poems and asked if anybody wanted to arm wrestle.” (Someone did; naturally Bukowski won.) In “On Drinking,” his escapades are entirely typical and roughly as follows: He goes to, copes with or barely avoids jail. He mouths off to cops. He gets into unprovoked fistfights that take three pages to describe and that involve dozens of barehanded punches to the head. He offers to clean a bar’s dirty blinds for money and whiskey, and then, Tom Sawyer-style, persuades the other patrons to do the job for him. He is coated in vomit and/or blood with the regularity of an E.R. nurse. He pleasures, or fails to pleasure, scores of women, none of whom are dissuaded by the foregoing vomit or blood. And he wants nothing to do with modern writers who “lecture at universities / in tie and suit, / the little boys soberly studious, / the little girls with glazed eyes.” This boozy, cartoon machismo has generally served Bukowski well, in the sense that 25 years after his death he still has a sizable audience by the standards of a fiction writer and a colossal audience by the standards of a poet. As you might expect, that readership is not there for displays of technical prowess. The poems in “On Drinking” are distinguishable from the prose mostly by virtue of line breaks that are inserted in why-not fashion; as in, “once in Paris / drunk on national TV / before 50 million Frenchmen / I began babbling vulgar thoughts / and when the host put his hand over my / mouth / I leaped up from the round table …” There’s basically no difference between these lines and the prose narrative that precedes them, except that the prose involves an extended brawl while the poem includes Bukowski pulling a knife on some French security guards.

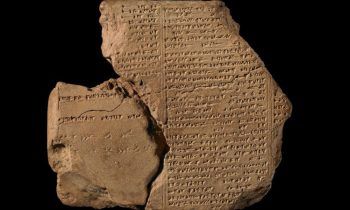

This boozy, cartoon machismo has generally served Bukowski well, in the sense that 25 years after his death he still has a sizable audience by the standards of a fiction writer and a colossal audience by the standards of a poet. As you might expect, that readership is not there for displays of technical prowess. The poems in “On Drinking” are distinguishable from the prose mostly by virtue of line breaks that are inserted in why-not fashion; as in, “once in Paris / drunk on national TV / before 50 million Frenchmen / I began babbling vulgar thoughts / and when the host put his hand over my / mouth / I leaped up from the round table …” There’s basically no difference between these lines and the prose narrative that precedes them, except that the prose involves an extended brawl while the poem includes Bukowski pulling a knife on some French security guards. The Epic of Gilgamesh is a Babylonian poem composed in ancient Iraq, millennia before Homer. It tells the story of Gilgamesh, king of the city of Uruk. To curb his restless and destructive energy, the gods create a friend for him, Enkidu, who grows up among the animals of the steppe. When Gilgamesh hears about this wild man, he orders that a woman named Shamhat be brought out to find him. Shamhat seduces Enkidu, and the two make love for six days and seven nights, transforming Enkidu from beast to man. His strength is diminished, but his intellect is expanded, and he becomes able to think and speak like a human being. Shamhat and Enkidu travel together to a camp of shepherds, where Enkidu learns the ways of humanity. Eventually, Enkidu goes to Uruk to confront Gilgamesh’s abuse of power, and the two heroes wrestle with one another, only to form a passionate friendship.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a Babylonian poem composed in ancient Iraq, millennia before Homer. It tells the story of Gilgamesh, king of the city of Uruk. To curb his restless and destructive energy, the gods create a friend for him, Enkidu, who grows up among the animals of the steppe. When Gilgamesh hears about this wild man, he orders that a woman named Shamhat be brought out to find him. Shamhat seduces Enkidu, and the two make love for six days and seven nights, transforming Enkidu from beast to man. His strength is diminished, but his intellect is expanded, and he becomes able to think and speak like a human being. Shamhat and Enkidu travel together to a camp of shepherds, where Enkidu learns the ways of humanity. Eventually, Enkidu goes to Uruk to confront Gilgamesh’s abuse of power, and the two heroes wrestle with one another, only to form a passionate friendship. When you’re setting up fake Facebook pages, it’s the little details that can mess things up. On a group computer call last winter, Susan Gerbic was going through her checklist of tips for her team’s latest sting operation — this one focused on infiltrating the audience of a psychic. It all started with maintaining their Facebook sock puppets — those fake online profiles. “American spellings everyone!” she commanded her half-dozen international colleagues through the Skype crackle.

When you’re setting up fake Facebook pages, it’s the little details that can mess things up. On a group computer call last winter, Susan Gerbic was going through her checklist of tips for her team’s latest sting operation — this one focused on infiltrating the audience of a psychic. It all started with maintaining their Facebook sock puppets — those fake online profiles. “American spellings everyone!” she commanded her half-dozen international colleagues through the Skype crackle. Appropriately, given that they follow the arc of a marriage, the letters are filled with what Plath calls at one point “domesticalia.” The exhaustive reports on furniture, cooking, renovations, and real estate aren’t thrilling, but neither are they boring, being possessed of a kind of homely tactile truth that is revealing and hypnotic in its way. For a dinner party in December 1957, when Plath was teaching at Smith, she “tossed off a sponge cake” from a recipe her mother had sent her. “Made my little parfait with 6 egg yolks, maple syrup & 2 cups of heavy cream, frozen, mixed up a delicious spaghetti sauce, a French salad dressing, a salad of lettuce, romaine & chicory & scallions, garlic butter for French bread, and the clam-and-sour-cream dip I learned from Mrs. Graham. . . . We served sherry & hot potato chips & this dip for beginning & then you should see how nice our round table looked, if a bit crowded, with my lovely West German linen cloth (pale nubbly yellow). . . . I’ve never made a meal for 6 before, just 4.” On occasion, the mundane stories suggest a kind of unsettling foreknowledge.

Appropriately, given that they follow the arc of a marriage, the letters are filled with what Plath calls at one point “domesticalia.” The exhaustive reports on furniture, cooking, renovations, and real estate aren’t thrilling, but neither are they boring, being possessed of a kind of homely tactile truth that is revealing and hypnotic in its way. For a dinner party in December 1957, when Plath was teaching at Smith, she “tossed off a sponge cake” from a recipe her mother had sent her. “Made my little parfait with 6 egg yolks, maple syrup & 2 cups of heavy cream, frozen, mixed up a delicious spaghetti sauce, a French salad dressing, a salad of lettuce, romaine & chicory & scallions, garlic butter for French bread, and the clam-and-sour-cream dip I learned from Mrs. Graham. . . . We served sherry & hot potato chips & this dip for beginning & then you should see how nice our round table looked, if a bit crowded, with my lovely West German linen cloth (pale nubbly yellow). . . . I’ve never made a meal for 6 before, just 4.” On occasion, the mundane stories suggest a kind of unsettling foreknowledge. What is missing in Clapton’s imitation of African American musical tradition on Unplugged, which Chicago Tribune critic Greg Kot fairly described as “a blues album for yuppies,” is the quality most responsible for the music’s sadness as well as its humor, lasting relevance, and political bite: that is, a profound self-awareness. As Eric Lott writes in Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (1993), whose title Bob Dylan lifted for his 2001 record, “Minstrelsy brought to public form racialized elements of thought and feeling, tone and impulse, residing at the very edge of semantic availability, which Americans only dimly realized they felt, let alone understood.” The antebellum minstrel show, whose enthusiasts included Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Abraham Lincoln, was an expression of white America’s ambivalence toward its own culture of self-proclaimed supremacy; “the whites involved in minstrelsy,” Lott writes, “were far from unenthusiastic about black cultural practices or, conversely, untroubled by them, continuous though the economic logic of blackface was with slavery.”

What is missing in Clapton’s imitation of African American musical tradition on Unplugged, which Chicago Tribune critic Greg Kot fairly described as “a blues album for yuppies,” is the quality most responsible for the music’s sadness as well as its humor, lasting relevance, and political bite: that is, a profound self-awareness. As Eric Lott writes in Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (1993), whose title Bob Dylan lifted for his 2001 record, “Minstrelsy brought to public form racialized elements of thought and feeling, tone and impulse, residing at the very edge of semantic availability, which Americans only dimly realized they felt, let alone understood.” The antebellum minstrel show, whose enthusiasts included Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Abraham Lincoln, was an expression of white America’s ambivalence toward its own culture of self-proclaimed supremacy; “the whites involved in minstrelsy,” Lott writes, “were far from unenthusiastic about black cultural practices or, conversely, untroubled by them, continuous though the economic logic of blackface was with slavery.”