Raymond Geuss in The Point:

Raymond Geuss in The Point:

When I talk with Brexiteers, I certainly do not assume that what Habermas calls the “power of the better argument” will be irresistible. And I am certainly very far from assuming that an indefinite discussion conducted under ideal circumstances would eventually free them from the cognitive and moral distortions from which they suffer, and in the end lead to a consensus between them and me. What makes situations like this difficult is that arguments are relatively ineffectual against appeals to “identity.” In the nineteenth century Kierkegaard was very familiar with this phenomenon, and much of his philosophizing is devoted to trying to make sense of and come to terms with it. “We do not under any circumstances wish to be confused with Europeans because we have nothing but contempt for them.” What is one to say to that? Only real long-term sociopolitical transformations, impinging external events and well-focused, sustained political intervention have any chance of having an effect. In the long run, however, as Keynes so clearly put it, we are all dead.

When, at the beginning of his Minima Moralia, Adorno expressed grave reservations about the “liberal fiction which holds that any and every thought must be universally communicable to anyone whatever,” he was criticizing both political liberalism and the use of “communication” as a fundamental organizing principle in philosophy. This hostility toward both liberalism and the fetish of universal communication, on the other, was not maintained by the members of the so-called Frankfurt School and was abandoned even before the next generation had fully come on the scene. Even as early as the beginning of the 1970s, the unofficial successor of Adorno as head of the school, Jürgen Habermas, who turns ninety this week, began his project of rehabilitating a neo-Kantian version of liberalism.

More here.

Kim Yi Dionne over at the WaPo’s The Monkey Cage:

Kim Yi Dionne over at the WaPo’s The Monkey Cage: William Hazlitt

William Hazlitt Which brings me to the question of just why Les’s poetry — the poetry of the ‘bush’, and not the poetry of the ‘street’ or city say. It must be remembered (as Guy Debord told us in The Society of the Spectacle) that the aesthetic credo under Capitalism is ‘That which appears is good, that which is good appears’ — cos aesthetics is also a socially-constructed activity, and our heads have been steered, not only towards the bush, but away from the sea or city, or anything else starting with C. John Kinsella sez in his posthumous tribute that Les ‘strangely’ had ‘more in common with many experimentalists than with the more conservative traditionalists who lionise him’ — which i suggest you take with a grain of salt — as one wonders what Kinsella means by the word ‘experimentalists’ here — no family that i belong to that’s for sure.

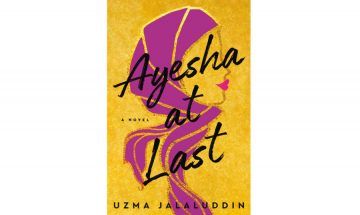

Which brings me to the question of just why Les’s poetry — the poetry of the ‘bush’, and not the poetry of the ‘street’ or city say. It must be remembered (as Guy Debord told us in The Society of the Spectacle) that the aesthetic credo under Capitalism is ‘That which appears is good, that which is good appears’ — cos aesthetics is also a socially-constructed activity, and our heads have been steered, not only towards the bush, but away from the sea or city, or anything else starting with C. John Kinsella sez in his posthumous tribute that Les ‘strangely’ had ‘more in common with many experimentalists than with the more conservative traditionalists who lionise him’ — which i suggest you take with a grain of salt — as one wonders what Kinsella means by the word ‘experimentalists’ here — no family that i belong to that’s for sure. Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” has given birth to a cottage industry of sequels, variations, and modernizations, from “Bridget Jones’s Diary” or the Bollywood film “Bride and Prejudice,” to “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.” Now comes an update set among Muslim Canadians, “Ayesha at Last,” the debut novel of Uzma Jalaluddin, who writes a humorous advice column on parenting for the Toronto Star. Does the world need “Pride and Prejudice and Muslims”? Indeed, it does – at least, it needs Jalaluddin’s version, which is full of wit and verve and humor. Like “Pride and Prejudice,” “Ayesha at Last” is not just about a heroine finding her man, but how she navigates her small community’s narrow expectations for women and her family’s foibles and financial struggles, finding strength in her voice.

Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” has given birth to a cottage industry of sequels, variations, and modernizations, from “Bridget Jones’s Diary” or the Bollywood film “Bride and Prejudice,” to “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.” Now comes an update set among Muslim Canadians, “Ayesha at Last,” the debut novel of Uzma Jalaluddin, who writes a humorous advice column on parenting for the Toronto Star. Does the world need “Pride and Prejudice and Muslims”? Indeed, it does – at least, it needs Jalaluddin’s version, which is full of wit and verve and humor. Like “Pride and Prejudice,” “Ayesha at Last” is not just about a heroine finding her man, but how she navigates her small community’s narrow expectations for women and her family’s foibles and financial struggles, finding strength in her voice. In 1969, when the New York police raided the Stonewall Inn and encountered unexpected resistance from LGBT protesters, homosexuality was still criminalised in most countries. Even in more tolerant societies, venturing out of the closet was often akin to social and professional suicide. Today, in contrast, the prime minister of Serbia is openly lesbian and the prime minister of Ireland is proudly gay, as are the CEO of Apple and numerous other politicians, businesspeople, artists and scientists. In the United States, the average Republican today holds far more liberal views on LGBT issues than the average Democrat held in 1969. The argument has moved from “should the state imprison LGBT people?” to “should the state recognise same-sex marriage?” (and almost

In 1969, when the New York police raided the Stonewall Inn and encountered unexpected resistance from LGBT protesters, homosexuality was still criminalised in most countries. Even in more tolerant societies, venturing out of the closet was often akin to social and professional suicide. Today, in contrast, the prime minister of Serbia is openly lesbian and the prime minister of Ireland is proudly gay, as are the CEO of Apple and numerous other politicians, businesspeople, artists and scientists. In the United States, the average Republican today holds far more liberal views on LGBT issues than the average Democrat held in 1969. The argument has moved from “should the state imprison LGBT people?” to “should the state recognise same-sex marriage?” (and almost  What did you think of the last commercial you watched? Was it funny? Confusing? Would you buy the product? You might not remember or know for certain how you felt, but increasingly, machines do. New artificial intelligence technologies are learning and recognizing human emotions, and using that knowledge to improve everything from marketing campaigns to health care.

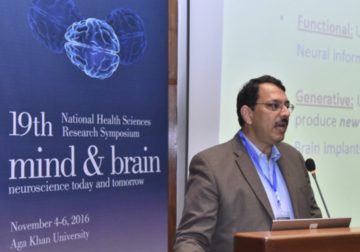

What did you think of the last commercial you watched? Was it funny? Confusing? Would you buy the product? You might not remember or know for certain how you felt, but increasingly, machines do. New artificial intelligence technologies are learning and recognizing human emotions, and using that knowledge to improve everything from marketing campaigns to health care. ALI: Both. AI poses many dangers that people are now waking up to, such as biases in automated decision-making, the creation of hyper-realistic false information, the profiling and micro-targeting of people for commercial exploitation. And then there is the fear that AI will take away millions of jobs. One area where there’s serious alarm is autonomous weapons. Every technology that can be used as a weapon ultimately has been throughout history. It is guaranteed to happen with AI. In principle, when you have an intelligent weapon, it could reduce unintended casualties, but it will also be much more lethal and tempting to use. That’s why it is critical to develop rules and treaties for intelligent autonomous munitions just as we have for nuclear, chemical and biological weapons. Unfortunately, military imperatives often trump regulations and treaties.

ALI: Both. AI poses many dangers that people are now waking up to, such as biases in automated decision-making, the creation of hyper-realistic false information, the profiling and micro-targeting of people for commercial exploitation. And then there is the fear that AI will take away millions of jobs. One area where there’s serious alarm is autonomous weapons. Every technology that can be used as a weapon ultimately has been throughout history. It is guaranteed to happen with AI. In principle, when you have an intelligent weapon, it could reduce unintended casualties, but it will also be much more lethal and tempting to use. That’s why it is critical to develop rules and treaties for intelligent autonomous munitions just as we have for nuclear, chemical and biological weapons. Unfortunately, military imperatives often trump regulations and treaties. David Chalmers: I think artificial general intelligence is possible. Some people are really hyping up A.I., saying that artificial general intelligence is just around the corner in maybe 10 or 20 years. I would be surprised if they turn out to be right. There has been a lot of exciting progress recently with deep learning, which focuses on methods of pattern-finding in raw data.

David Chalmers: I think artificial general intelligence is possible. Some people are really hyping up A.I., saying that artificial general intelligence is just around the corner in maybe 10 or 20 years. I would be surprised if they turn out to be right. There has been a lot of exciting progress recently with deep learning, which focuses on methods of pattern-finding in raw data. Between 1948 and 1952 there took place a particularly remarkable correspondence: that between Samuel Beckett and Georges Duthuit. In the course of his life Beckett wrote something approaching 20,000 letters. Fascinating as many of these are, they offer nothing that can match this explosion of words. But then Duthuit was not just any correspondent: he was a highly cultured and intellectually rigorous art historian and critic, with total confidence in his own judgement. For Beckett, recognising these qualities and drawn by Duthuit’s impatient refusal of cultural orthodoxies, he represented something close to an ideal interlocutor: someone to whom, in the areas that mattered, anything could be said.

Between 1948 and 1952 there took place a particularly remarkable correspondence: that between Samuel Beckett and Georges Duthuit. In the course of his life Beckett wrote something approaching 20,000 letters. Fascinating as many of these are, they offer nothing that can match this explosion of words. But then Duthuit was not just any correspondent: he was a highly cultured and intellectually rigorous art historian and critic, with total confidence in his own judgement. For Beckett, recognising these qualities and drawn by Duthuit’s impatient refusal of cultural orthodoxies, he represented something close to an ideal interlocutor: someone to whom, in the areas that mattered, anything could be said. Henry James did not wish to be known by his readers. He remained oddly absent in his fiction. He did not dramatize his own opinions or offer aphorisms about life, as George Eliot, a novelist whom James followed closely, did. Instead, he worked intensely on his characters, offering their consciousness and motives a great deal of nuance and detail and ambiguity.

Henry James did not wish to be known by his readers. He remained oddly absent in his fiction. He did not dramatize his own opinions or offer aphorisms about life, as George Eliot, a novelist whom James followed closely, did. Instead, he worked intensely on his characters, offering their consciousness and motives a great deal of nuance and detail and ambiguity. Natalia Ginzburg is the last woman left on earth. The rest are all men—even the female forms that can be seen moving about belong, ultimately, to this man’s world. A world where men make the decisions, the choices, take action. Ginzburg, or rather the disillusioned heroines who stand in for her, is alone, on the outside. There are generations and generations of women who have done nothing but wait and obey; wait to be loved, to get married, to become mothers, to be betrayed. So it is for her heroines.

Natalia Ginzburg is the last woman left on earth. The rest are all men—even the female forms that can be seen moving about belong, ultimately, to this man’s world. A world where men make the decisions, the choices, take action. Ginzburg, or rather the disillusioned heroines who stand in for her, is alone, on the outside. There are generations and generations of women who have done nothing but wait and obey; wait to be loved, to get married, to become mothers, to be betrayed. So it is for her heroines. I’m intrigued. Is creativity a skill I can beef up like a weak muscle? Absolutely, says Mark Runco, a cognitive psychologist who studies creativity at the University of Georgia, Athens. “Everybody has creative potential, and most of us have quite a bit of room for growth,” he says. “That doesn’t mean anybody can be Picasso or Einstein, but it does mean we can all learn to be more creative.” After all, creativity may be the key to Homo sapiens’ success. As a society, we dreamed up stone tools, the combustion engine, and all the things in the SkyMall catalog. “Our species is not fast. We’re not terribly strong. We can’t camouflage ourselves,” Puccio told me when we spoke on the phone. “What we do have is the ability to imagine and create new possibilities.” Creativity is certainly a buzzword these days. Amazon lists more than 6,000 self-help titles devoted to the subject. A handful of universities now offer master’s degrees in creativity, and a growing number of schools offer an undergraduate minor in creative thinking. “We’ve moved beyond the industrial economy and the knowledge economy. We’re now in the innovation economy,” Puccio says. “Creativity is a necessary skill to be successful in the work world. It’s not a luxury anymore to be creative. It’s an absolute necessity.”

I’m intrigued. Is creativity a skill I can beef up like a weak muscle? Absolutely, says Mark Runco, a cognitive psychologist who studies creativity at the University of Georgia, Athens. “Everybody has creative potential, and most of us have quite a bit of room for growth,” he says. “That doesn’t mean anybody can be Picasso or Einstein, but it does mean we can all learn to be more creative.” After all, creativity may be the key to Homo sapiens’ success. As a society, we dreamed up stone tools, the combustion engine, and all the things in the SkyMall catalog. “Our species is not fast. We’re not terribly strong. We can’t camouflage ourselves,” Puccio told me when we spoke on the phone. “What we do have is the ability to imagine and create new possibilities.” Creativity is certainly a buzzword these days. Amazon lists more than 6,000 self-help titles devoted to the subject. A handful of universities now offer master’s degrees in creativity, and a growing number of schools offer an undergraduate minor in creative thinking. “We’ve moved beyond the industrial economy and the knowledge economy. We’re now in the innovation economy,” Puccio says. “Creativity is a necessary skill to be successful in the work world. It’s not a luxury anymore to be creative. It’s an absolute necessity.” This week,

This week,  The field of

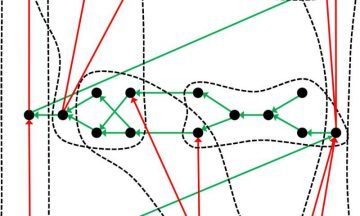

The field of  The periodic table of elements that most chemistry books depict is only one special case. This tabular overview of the chemical elements, which goes back to Dmitri Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer and the approaches of other chemists to organize the elements, involve different forms of representation of a hidden structure of the chemical elements. This is the conclusion reached by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences in Leipzig and the University of Leipzig in a recent paper. The mathematical approach of the Leipzig scientists is very general and can provide many different periodic systems depending on the principle of order and classification—not only for chemistry, but also for many other fields of knowledge.

The periodic table of elements that most chemistry books depict is only one special case. This tabular overview of the chemical elements, which goes back to Dmitri Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer and the approaches of other chemists to organize the elements, involve different forms of representation of a hidden structure of the chemical elements. This is the conclusion reached by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences in Leipzig and the University of Leipzig in a recent paper. The mathematical approach of the Leipzig scientists is very general and can provide many different periodic systems depending on the principle of order and classification—not only for chemistry, but also for many other fields of knowledge. There does economic power come from? Does it exist independently of the law? It seems obvious, even undeniable, that the answer is no. Law creates, defines and enforces property rights. Law enforces private contracts. It charters corporations and shields investors from liability. Law declares illegal certain contracts of economic cooperation between separate individuals – which it calls ‘price-fixing’ – but declares economically equivalent activity legal when it takes place within a business firm or is controlled by one.

There does economic power come from? Does it exist independently of the law? It seems obvious, even undeniable, that the answer is no. Law creates, defines and enforces property rights. Law enforces private contracts. It charters corporations and shields investors from liability. Law declares illegal certain contracts of economic cooperation between separate individuals – which it calls ‘price-fixing’ – but declares economically equivalent activity legal when it takes place within a business firm or is controlled by one.