Matt Frost in The New Atlantis:

The Italian Renaissance humanist Girolamo Fracastoro is best remembered for his allegorical poem about syphilis. But his interests were expansive. Around 1550 he wrote a letter to Alvise Cornaro, a nobleman skilled in hydraulics, worrying that a crisis loomed for the Most Serene Republic of Venice. The rivers of the region, stripped of trees to feed the city’s growth, were filling the otherwise navigable channels of the lagoon with silt, forming pestilent marshlands and rendering the waterways impassable. At the same time, sea levels were falling. Venetians had known for centuries that their public health and maritime advantage depended on the precious lagoon, and the crisis had long preoccupied the republic’s leadership. Fracastoro told Cornaro:

The Italian Renaissance humanist Girolamo Fracastoro is best remembered for his allegorical poem about syphilis. But his interests were expansive. Around 1550 he wrote a letter to Alvise Cornaro, a nobleman skilled in hydraulics, worrying that a crisis loomed for the Most Serene Republic of Venice. The rivers of the region, stripped of trees to feed the city’s growth, were filling the otherwise navigable channels of the lagoon with silt, forming pestilent marshlands and rendering the waterways impassable. At the same time, sea levels were falling. Venetians had known for centuries that their public health and maritime advantage depended on the precious lagoon, and the crisis had long preoccupied the republic’s leadership. Fracastoro told Cornaro:

This Lagoon must someday — only God knows when — dry out of sea water and become swampy, either from silt, or from the withdrawal of the sea from the whole bay, one or the other; I do not believe that any human power can oppose it.

Yet he exhorted Cornaro to action anyway. Fracastoro’s idea was to flood the lagoon with fresh water. The plan was partially implemented but backfired, spreading muck across an even greater area. So the city then spent fortunes on diverting the silty rivers away from the lagoon and into the sea. Eventually, this strategy worked. Like the siltation that worried Fracastoro and Cornaro, climate change is a slow, relentless environmental crisis, but one of far greater scale and complexity. Our challenge, however, is the same: to carry our thriving civilization into a future made perilously uncertain by the side effects of our own prosperity. Each of us constitutes a link between the past and the future, and we share a human need to participate in the life of something that perdures beyond our own years. This is the conservationist — and arguably the conservative — argument for combating climate change: Our descendants, who will have a great deal in common with us, ought to be able to enjoy conditions similar to those that permitted us and our forebears to thrive.

More here.

Albert Einstein famously said that quantum mechanics should allow two objects to affect each other’s behaviour instantly across vast distances, something he

Albert Einstein famously said that quantum mechanics should allow two objects to affect each other’s behaviour instantly across vast distances, something he  In September 2009, over 3,000 bee enthusiasts from around the world descended on the city of Montpellier in southern France for Apimondia — a festive beekeeper conference filled with scientific lectures, hobbyist demonstrations, and commercial beekeepers hawking honey. But that year, a cloud loomed over the event: bee colonies across the globe were collapsing, and billions of bees were dying.

In September 2009, over 3,000 bee enthusiasts from around the world descended on the city of Montpellier in southern France for Apimondia — a festive beekeeper conference filled with scientific lectures, hobbyist demonstrations, and commercial beekeepers hawking honey. But that year, a cloud loomed over the event: bee colonies across the globe were collapsing, and billions of bees were dying. Serotonin is a story of psychic descent and personal disintegration, with a bloody political interlude grafted between its narrator’s initial crack-up and his terminal plunge. Florent-Claude Labrouste is forty-six years old and a veteran of the revolving door between the public and private French agricultural bureaucracies. His life has reached an erotic dead end. He’s a good-looking man, so he tells us, but it is a false front: “I have demonstrated my inability to take control of my life, the virility that seemed to emanate from my square face with its clear angles and chiselled features is in truth nothing but a decoy, a trick pure and simple—for which, it is true, I was not responsible.” He’s had a string of girlfriends, makes a good living, rents a big Paris flat, owns a vacation home in Spain, and has a substantial inheritance from his deceased parents, who were the opposite of abusive. And yet . . .

Serotonin is a story of psychic descent and personal disintegration, with a bloody political interlude grafted between its narrator’s initial crack-up and his terminal plunge. Florent-Claude Labrouste is forty-six years old and a veteran of the revolving door between the public and private French agricultural bureaucracies. His life has reached an erotic dead end. He’s a good-looking man, so he tells us, but it is a false front: “I have demonstrated my inability to take control of my life, the virility that seemed to emanate from my square face with its clear angles and chiselled features is in truth nothing but a decoy, a trick pure and simple—for which, it is true, I was not responsible.” He’s had a string of girlfriends, makes a good living, rents a big Paris flat, owns a vacation home in Spain, and has a substantial inheritance from his deceased parents, who were the opposite of abusive. And yet . . . Understood as a military struggle, slavery was a conflict staggering in its scale, even just in the Caribbean. Beginning in the seventeenth century, European traders prowled Africa’s Gold Coast looking to exchange guns, textiles, or even a bottle of brandy for able bodies; by the middle of the eighteenth century, slaves constituted ninety per cent of Europe’s trade with Africa. Of the more than ten million Africans who survived the journey across the Atlantic, six hundred thousand went to work in Jamaica, an island roughly the size of Connecticut. By contrast, four hundred thousand were sent to all of North America. (The domestic slave trade was another matter: by the time the Civil War began, there were roughly four million enslaved people living in the United States.)

Understood as a military struggle, slavery was a conflict staggering in its scale, even just in the Caribbean. Beginning in the seventeenth century, European traders prowled Africa’s Gold Coast looking to exchange guns, textiles, or even a bottle of brandy for able bodies; by the middle of the eighteenth century, slaves constituted ninety per cent of Europe’s trade with Africa. Of the more than ten million Africans who survived the journey across the Atlantic, six hundred thousand went to work in Jamaica, an island roughly the size of Connecticut. By contrast, four hundred thousand were sent to all of North America. (The domestic slave trade was another matter: by the time the Civil War began, there were roughly four million enslaved people living in the United States.) The Death of Jesus abounds in definitional disputes, hairline distinctions and logical paradoxes. When David needs a transfusion, there is dispute over whether blood is best understood by science or primal instinct; Dmitri thinks that the doctor’s “types” are less important than a donor’s personal affinity with the patient. Simón shifts the goalposts on whether David should be treated as “an exception”, depending on what kind of treatment (medical, pedagogical) he is requesting. David dismisses the legitimacy of the word “why” when he isn’t the one using it and insists that things “don’t have to be true to be true”. And towards the end, the reader is prompted to wonder if David’s end isn’t really a beginning? There’s a rumour that on dying you “wake up on some foreign shore” – as Simón and David did at the start of the first volume – and are forced “to play out the rigmarole all over again”.

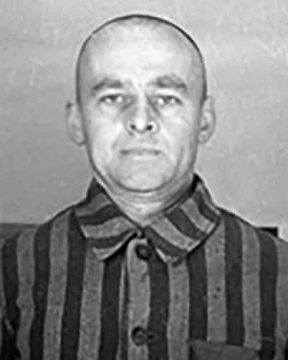

The Death of Jesus abounds in definitional disputes, hairline distinctions and logical paradoxes. When David needs a transfusion, there is dispute over whether blood is best understood by science or primal instinct; Dmitri thinks that the doctor’s “types” are less important than a donor’s personal affinity with the patient. Simón shifts the goalposts on whether David should be treated as “an exception”, depending on what kind of treatment (medical, pedagogical) he is requesting. David dismisses the legitimacy of the word “why” when he isn’t the one using it and insists that things “don’t have to be true to be true”. And towards the end, the reader is prompted to wonder if David’s end isn’t really a beginning? There’s a rumour that on dying you “wake up on some foreign shore” – as Simón and David did at the start of the first volume – and are forced “to play out the rigmarole all over again”. Just after Witold Pilecki’s arrival at

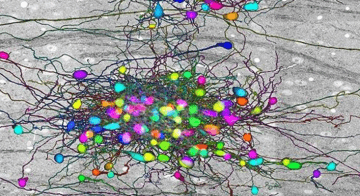

Just after Witold Pilecki’s arrival at  On a chilly evening last fall, I stared into nothingness out of the floor-to-ceiling windows in my office on the outskirts of Harvard’s campus. As a purplish-red sun set, I sat brooding over my dataset on rat brains. I thought of the cold windowless rooms in downtown Boston, home to Harvard’s high-performance computing center, where computer servers were holding on to a precious 48 terabytes of my data. I have recorded the 13 trillion numbers in this dataset as part of my Ph.D. experiments, asking how the visual parts of the rat brain respond to movement. Printed on paper, the dataset would fill 116 billion pages, double-spaced. When I recently finished writing the story of my data, the magnum opus fit on fewer than two dozen printed pages. Performing the experiments turned out to be the easy part. I had spent the last year agonizing over the data, observing and asking questions. The answers left out large chunks that did not pertain to the questions, like a map leaves out irrelevant details of a territory. But, as massive as my dataset sounds, it represents just a tiny chunk of a dataset taken from the whole brain. And the questions it asks—Do neurons in the visual cortex do anything when an animal can’t see? What happens when inputs to the visual cortex from other brain regions are shut off?—are small compared to the ultimate question in neuroscience: How does the brain work?

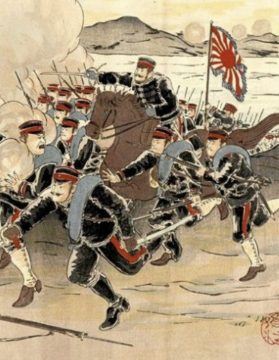

On a chilly evening last fall, I stared into nothingness out of the floor-to-ceiling windows in my office on the outskirts of Harvard’s campus. As a purplish-red sun set, I sat brooding over my dataset on rat brains. I thought of the cold windowless rooms in downtown Boston, home to Harvard’s high-performance computing center, where computer servers were holding on to a precious 48 terabytes of my data. I have recorded the 13 trillion numbers in this dataset as part of my Ph.D. experiments, asking how the visual parts of the rat brain respond to movement. Printed on paper, the dataset would fill 116 billion pages, double-spaced. When I recently finished writing the story of my data, the magnum opus fit on fewer than two dozen printed pages. Performing the experiments turned out to be the easy part. I had spent the last year agonizing over the data, observing and asking questions. The answers left out large chunks that did not pertain to the questions, like a map leaves out irrelevant details of a territory. But, as massive as my dataset sounds, it represents just a tiny chunk of a dataset taken from the whole brain. And the questions it asks—Do neurons in the visual cortex do anything when an animal can’t see? What happens when inputs to the visual cortex from other brain regions are shut off?—are small compared to the ultimate question in neuroscience: How does the brain work? I have a confession to make: I thought it distinctly odd that Norton asked me to translate The Art of War. Perhaps I am too used to gender stereotypes, but like many women who came of age during the Vietnam War, I shy away from violence (verbal and physical) and regard myself as a near-pacifist. Unsurprisingly, I associated the Chinese Art of War with “Kill, kill, kill,” since my first awareness of the text’s existence came during the early 1970s, soon after Brigadier General Griffith introduced his translation as a way to “know thy enemy.”

I have a confession to make: I thought it distinctly odd that Norton asked me to translate The Art of War. Perhaps I am too used to gender stereotypes, but like many women who came of age during the Vietnam War, I shy away from violence (verbal and physical) and regard myself as a near-pacifist. Unsurprisingly, I associated the Chinese Art of War with “Kill, kill, kill,” since my first awareness of the text’s existence came during the early 1970s, soon after Brigadier General Griffith introduced his translation as a way to “know thy enemy.” The Trump campaign ran on bringing jobs back to American shores, although mechanization has been the biggest reason for manufacturing jobs’ disappearance. Similar losses have led to populist movements in several other countries. But instead of a pro-job growth future, economists across the board predict further losses as AI, robotics, and other technologies continue to be ushered in. What is up for debate is how quickly this is likely to occur.

The Trump campaign ran on bringing jobs back to American shores, although mechanization has been the biggest reason for manufacturing jobs’ disappearance. Similar losses have led to populist movements in several other countries. But instead of a pro-job growth future, economists across the board predict further losses as AI, robotics, and other technologies continue to be ushered in. What is up for debate is how quickly this is likely to occur. How should one think of a nation, institution or company that has pioneered innovation and found solutions to seemingly unsolvable problems, but also has aspects we find objectionable, even despicable? How do we balance good and bad? Can we separate the two, or are they inexorably linked?

How should one think of a nation, institution or company that has pioneered innovation and found solutions to seemingly unsolvable problems, but also has aspects we find objectionable, even despicable? How do we balance good and bad? Can we separate the two, or are they inexorably linked? W

W For Hägglund what flows from the recognition that religious faith is incoherent is a revaluation of our relation to our finite lives that he calls secular faith—the faith that life is worth living, for itself, and not for some deferred or transcendent goal. But secular faith leads necessarily to another revaluation. When we realize that our time in this life is finite, we are compelled to ask the most fundamental of questions: what ought I to do with this time? Asking this question is at the core of what Hägglund calls spiritual freedom: “The ability to ask this question—the question of what we ought to do with our time—is the basic condition for what I call spiritual freedom. To lead a free, spiritual life (rather than a life determined merely by natural instincts), I must be responsible for what I do.”

For Hägglund what flows from the recognition that religious faith is incoherent is a revaluation of our relation to our finite lives that he calls secular faith—the faith that life is worth living, for itself, and not for some deferred or transcendent goal. But secular faith leads necessarily to another revaluation. When we realize that our time in this life is finite, we are compelled to ask the most fundamental of questions: what ought I to do with this time? Asking this question is at the core of what Hägglund calls spiritual freedom: “The ability to ask this question—the question of what we ought to do with our time—is the basic condition for what I call spiritual freedom. To lead a free, spiritual life (rather than a life determined merely by natural instincts), I must be responsible for what I do.”

The primary difficulty of interstellar communication is finding common ground between ourselves and other intelligent entities about which we can know nothing with absolute certainty. This common ground would be the basis for a universal language that could be understood by any intelligence, whether in the Milky Way, Andromeda, or beyond the cosmic horizon. To the best of our knowledge, the laws of physics are the same throughout the universe, which suggests that the facts of science may serve as a basis for mutual understanding between humans and an extraterrestrial intelligence. One key set of scientific facts presents an intriguing question. If aliens were to visit Earth and learn about its inhabitants, would they be surprised that such a wide variety of species all share a common genetic code? Or would this be all too familiar? There is probable cause to assume that the structure of genetic material is the same throughout the universe and that, while this is liable to give rise to life forms not found on Earth, the variety of species is fundamentally limited by the constraints built into the genetic mechanism.

The primary difficulty of interstellar communication is finding common ground between ourselves and other intelligent entities about which we can know nothing with absolute certainty. This common ground would be the basis for a universal language that could be understood by any intelligence, whether in the Milky Way, Andromeda, or beyond the cosmic horizon. To the best of our knowledge, the laws of physics are the same throughout the universe, which suggests that the facts of science may serve as a basis for mutual understanding between humans and an extraterrestrial intelligence. One key set of scientific facts presents an intriguing question. If aliens were to visit Earth and learn about its inhabitants, would they be surprised that such a wide variety of species all share a common genetic code? Or would this be all too familiar? There is probable cause to assume that the structure of genetic material is the same throughout the universe and that, while this is liable to give rise to life forms not found on Earth, the variety of species is fundamentally limited by the constraints built into the genetic mechanism.