Melissa Hogenboom in BBC:

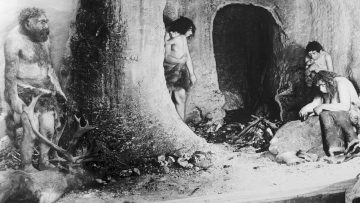

Forty thousand years ago in Europe, we were not the only human species alive – there were at least three others. Many of us are familiar with one of these, the Neanderthals. Distinguished by their stocky frames and heavy brows, they were remarkably like us and lived in many pockets of Europe for more than 300,000 years. For the most part, Neanderthals were a resilient group. They existed for about 200,000 years longer than we modern humans (Homo sapiens) have been alive. Evidence of their existence vanishes around 28,000 years ago – giving us an estimate for when they may, finally, have died off. Fossil evidence shows that, towards the end, the final few were clinging onto survival in places like Gibraltar. Findings from this British overseas territory, located at the southern tip of the Iberian peninsula, are helping us to understand more about what these last living Neanderthals were really like. And new insights reveal that they were much more like us than we once believed.

Forty thousand years ago in Europe, we were not the only human species alive – there were at least three others. Many of us are familiar with one of these, the Neanderthals. Distinguished by their stocky frames and heavy brows, they were remarkably like us and lived in many pockets of Europe for more than 300,000 years. For the most part, Neanderthals were a resilient group. They existed for about 200,000 years longer than we modern humans (Homo sapiens) have been alive. Evidence of their existence vanishes around 28,000 years ago – giving us an estimate for when they may, finally, have died off. Fossil evidence shows that, towards the end, the final few were clinging onto survival in places like Gibraltar. Findings from this British overseas territory, located at the southern tip of the Iberian peninsula, are helping us to understand more about what these last living Neanderthals were really like. And new insights reveal that they were much more like us than we once believed.

In recognition of this, Gibraltar received Unesco world heritage status in 2016. Of particular interest are four large caves. Three of these caves have barely been explored. But one of them, Gorham’s cave, is a site of yearly excavations. “They weren’t just surviving,” the Gibraltar museum’s director of archaeology Clive Finlayson tells me of its inhabitants.”It was in some way Neanderthal city,” he says. “This was the place with the highest concentration of Neanderthals anywhere in Europe.” It’s not known if this might amount to only dozens of people, or a few families, since genetic evidence also suggests that Neanderthals lived in “many small subpopulations”.

More here.

In her just-published “

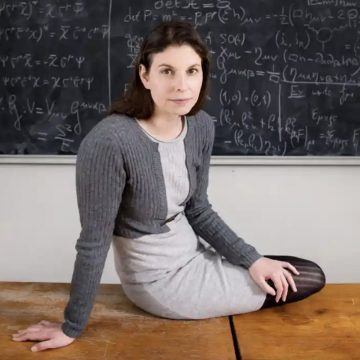

In her just-published “ The scientific work that I do on the brain basis of consciousness is sometimes misunderstood – a misunderstanding which I think comes mainly from the political divide between mystics and materialists. I am a materialist, and reactions to my work tend to follow along the lines of: ‘keep your scientific hands off my consciousness mystery’.

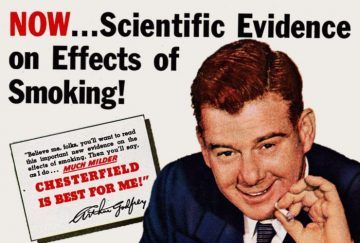

The scientific work that I do on the brain basis of consciousness is sometimes misunderstood – a misunderstanding which I think comes mainly from the political divide between mystics and materialists. I am a materialist, and reactions to my work tend to follow along the lines of: ‘keep your scientific hands off my consciousness mystery’. Decision makers atop today’s corporate structures are responsible for delivering short- and long-term financial returns, and in the pursuit of these goals they place profits and growth above all else. Avoidance of financial loss, to many corporate executives, is an alibi for just about any ugly decision. This is not to say that decisions at the highest level are black-and-white or simple; they are dictated by factors such as the cost of possible government regulation and potential loss of market share to less hazardous products. And, of course, companies are afraid of being sued by people sickened by their products, which costs money and can result in serious damage to the brand. All of this is part of the corporate calculus.

Decision makers atop today’s corporate structures are responsible for delivering short- and long-term financial returns, and in the pursuit of these goals they place profits and growth above all else. Avoidance of financial loss, to many corporate executives, is an alibi for just about any ugly decision. This is not to say that decisions at the highest level are black-and-white or simple; they are dictated by factors such as the cost of possible government regulation and potential loss of market share to less hazardous products. And, of course, companies are afraid of being sued by people sickened by their products, which costs money and can result in serious damage to the brand. All of this is part of the corporate calculus. My experience at the Auschwitz exhibit was a powerful one. But it was actually a familiar one. We are used to experiencing the horror of the Holocaust through the lens of Auschwitz. When we talk about the six million, we picture concentration camps, ghettos, cattle cars.

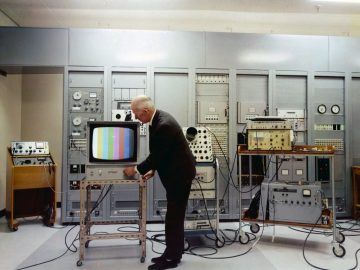

My experience at the Auschwitz exhibit was a powerful one. But it was actually a familiar one. We are used to experiencing the horror of the Holocaust through the lens of Auschwitz. When we talk about the six million, we picture concentration camps, ghettos, cattle cars. How much our historical context informs our perceptions of and beliefs about color is ably illustrated by Susan Murray’s award-winning book Bright Signals. Tracing the evolution of color television in America from the late 1920s to the early 1970s, the book successfully demonstrates how the medium reflected and refracted American social and political history, despite its initially halting, tentative development. Industry leaders, Murray shows, only progressively overcame regulators’, advertisers’, and the public’s initial resistance to color television as a finicky luxury.

How much our historical context informs our perceptions of and beliefs about color is ably illustrated by Susan Murray’s award-winning book Bright Signals. Tracing the evolution of color television in America from the late 1920s to the early 1970s, the book successfully demonstrates how the medium reflected and refracted American social and political history, despite its initially halting, tentative development. Industry leaders, Murray shows, only progressively overcame regulators’, advertisers’, and the public’s initial resistance to color television as a finicky luxury. What moves you to stand in the presence of the house, the landscape, the objects of a writer whom you so admire? Why are literary pilgrimages so compelling?

What moves you to stand in the presence of the house, the landscape, the objects of a writer whom you so admire? Why are literary pilgrimages so compelling?  Just off the coast of Espírito Santo, an island in the Vanuatu archipelago of the South Western Pacific, there is a massive underwater dump. Called Million Dollar Point after the millions of dollars worth of material disposed there, the dump is a popular diving destination, and divers report an amazing quantity of wreckage: jeeps, six-wheel drive trucks, bulldozers, semi-trailers, fork lifts, tractors, bound sheets of corrugated iron, unopened boxes of clothing, and cases of Coca-Cola. The dumped goods were not abandoned by the ni-Vanuatu people, nor by the Franco-British Condominium who ruled Vanuatu (then known as the New Hebrides) from 1906 until 1980, but by personnel of a WWII American military base named Buttons. At the end of the war, sometime between August 1945 and December 1947, the US military interred supplies, equipment, and vehicles under water.

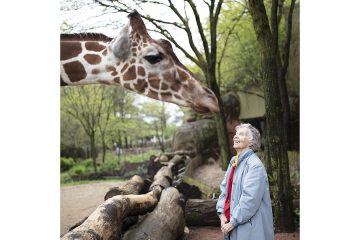

Just off the coast of Espírito Santo, an island in the Vanuatu archipelago of the South Western Pacific, there is a massive underwater dump. Called Million Dollar Point after the millions of dollars worth of material disposed there, the dump is a popular diving destination, and divers report an amazing quantity of wreckage: jeeps, six-wheel drive trucks, bulldozers, semi-trailers, fork lifts, tractors, bound sheets of corrugated iron, unopened boxes of clothing, and cases of Coca-Cola. The dumped goods were not abandoned by the ni-Vanuatu people, nor by the Franco-British Condominium who ruled Vanuatu (then known as the New Hebrides) from 1906 until 1980, but by personnel of a WWII American military base named Buttons. At the end of the war, sometime between August 1945 and December 1947, the US military interred supplies, equipment, and vehicles under water. When Canadian biologist Anne Innis Dagg was 3 years old, her mother took her to the zoo for the first time. There she saw her first giraffe, and a lifelong love affair ensued. And who can blame her? Is there any other four-legged creature whose looks are more magisterially goofy? Dagg is the focus of Alison Reid’s “The Woman Who Loves Giraffes,” and it confirms a long-held tenet of mine: If the subject of a documentary is fascinating, it doesn’t much matter if the filmmaking is workmanlike. Now in her 80s, Dagg is such a singular personality that everything about her seems sprightly and newly minted.

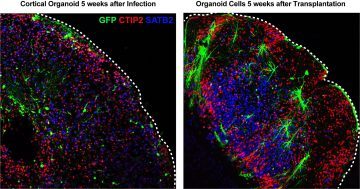

When Canadian biologist Anne Innis Dagg was 3 years old, her mother took her to the zoo for the first time. There she saw her first giraffe, and a lifelong love affair ensued. And who can blame her? Is there any other four-legged creature whose looks are more magisterially goofy? Dagg is the focus of Alison Reid’s “The Woman Who Loves Giraffes,” and it confirms a long-held tenet of mine: If the subject of a documentary is fascinating, it doesn’t much matter if the filmmaking is workmanlike. Now in her 80s, Dagg is such a singular personality that everything about her seems sprightly and newly minted. Brain organoids—three-dimensional balls of brain-like tissue grown in the lab, often from human stem cells—have been touted for their potential to let scientists study the formation of the brain’s complex circuitry in controlled laboratory conditions. The discussion surrounding brain organoids has been effusive, with some scientists suggesting they will make it possible to rapidly develop treatments for devastating brain diseases and others warning that organoids may soon attain some form of consciousness. But a new UC San Francisco study offers a more restrained perspective, by showing that widely used

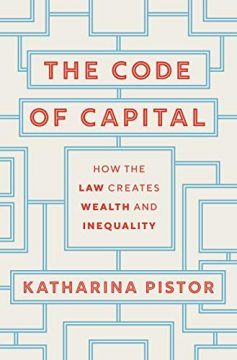

Brain organoids—three-dimensional balls of brain-like tissue grown in the lab, often from human stem cells—have been touted for their potential to let scientists study the formation of the brain’s complex circuitry in controlled laboratory conditions. The discussion surrounding brain organoids has been effusive, with some scientists suggesting they will make it possible to rapidly develop treatments for devastating brain diseases and others warning that organoids may soon attain some form of consciousness. But a new UC San Francisco study offers a more restrained perspective, by showing that widely used  “There is an estate in the realm more powerful than either your Lordship or the other House of Parliament,” one Lord Campbell proclaimed to the peers in the House of Lords, in 1851, “and that [is] the country solicitors.” It was the lawyers, in other words, who kept England’s landed elite so very, well, elite: who shielded and extended the wealth of the landowners, even granting them legal protection against their own creditors. How did they pull off this trick? Through a nimble tangle of contracts, carefully and complicatedly applied, as Katharina Pistor explains in her lucid new book, The Code of Capital: by mixing “modern notions of individual property rights with feudalist restrictions on alienability”; by employing trusts “to protect family estates, but then [turning] around and [using] the trust again to set aside assets for creditors so that they would roll over the debt of the life tenant one more time”; and by settling the rights to the estate among family members in line for inheritance. Solicitors maximized their clients’ profits and worth through strategic applications of the central institutions at their disposal: “contract, property, collateral, trust, corporate, and bankruptcy law,” what Pistor calls an “empire of law.”

“There is an estate in the realm more powerful than either your Lordship or the other House of Parliament,” one Lord Campbell proclaimed to the peers in the House of Lords, in 1851, “and that [is] the country solicitors.” It was the lawyers, in other words, who kept England’s landed elite so very, well, elite: who shielded and extended the wealth of the landowners, even granting them legal protection against their own creditors. How did they pull off this trick? Through a nimble tangle of contracts, carefully and complicatedly applied, as Katharina Pistor explains in her lucid new book, The Code of Capital: by mixing “modern notions of individual property rights with feudalist restrictions on alienability”; by employing trusts “to protect family estates, but then [turning] around and [using] the trust again to set aside assets for creditors so that they would roll over the debt of the life tenant one more time”; and by settling the rights to the estate among family members in line for inheritance. Solicitors maximized their clients’ profits and worth through strategic applications of the central institutions at their disposal: “contract, property, collateral, trust, corporate, and bankruptcy law,” what Pistor calls an “empire of law.”

Cosmologists don’t enter their profession to tackle the easy questions, but there is one paradox that has reached staggering proportions.

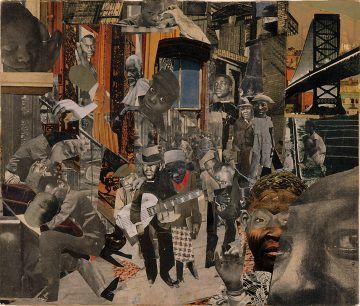

Cosmologists don’t enter their profession to tackle the easy questions, but there is one paradox that has reached staggering proportions. The artist Jack Whitten, who died in 2018, approached his practice with the curiosity of a scientist and the playfulness of a jazz musician. Many of his paintings are the result of a careful aesthetic hypothesis unleashed upon the canvas and then transformed by improvisation. The works at the center of “

The artist Jack Whitten, who died in 2018, approached his practice with the curiosity of a scientist and the playfulness of a jazz musician. Many of his paintings are the result of a careful aesthetic hypothesis unleashed upon the canvas and then transformed by improvisation. The works at the center of “ In 1953,

In 1953,  ON OCTOBER

ON OCTOBER