Peter Waldman in Bloomberg News:

The dossier on cancer researcher Xifeng Wu was thick with intrigue, if hardly the stuff of a spy thriller. It contained findings that she’d improperly shared confidential information and accepted a half-dozen advisory roles at medical institutions in China. She might have weathered those allegations, but for a larger aspersion that was far more problematic: She was branded an oncological double agent. In recent decades, cancer research has become increasingly globalized, with scientists around the world pooling data and ideas to jointly study a disease that kills almost 10 million people a year. International collaborations are an intrinsic part of the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s Moonshot program, the government’s $1 billion blitz to double the pace of treatment discoveries by 2022. One of the program’s tag lines: “Cancer knows no borders.”

The dossier on cancer researcher Xifeng Wu was thick with intrigue, if hardly the stuff of a spy thriller. It contained findings that she’d improperly shared confidential information and accepted a half-dozen advisory roles at medical institutions in China. She might have weathered those allegations, but for a larger aspersion that was far more problematic: She was branded an oncological double agent. In recent decades, cancer research has become increasingly globalized, with scientists around the world pooling data and ideas to jointly study a disease that kills almost 10 million people a year. International collaborations are an intrinsic part of the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s Moonshot program, the government’s $1 billion blitz to double the pace of treatment discoveries by 2022. One of the program’s tag lines: “Cancer knows no borders.”

Except, it turns out, the borders around China. In January, Wu, an award-winning epidemiologist and naturalized American citizen, quietly stepped down as director of the Center for Public Health and Translational Genomics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center after a three-month investigation into her professional ties in China. Her resignation, and the departures in recent months of three other top Chinese American scientists from Houston-based MD Anderson, stem from a Trump administration drive to counter Chinese influence at U.S. research institutions. The aim is to stanch China’s well-documented and costly theft of U.S. innovation and know-how. The collateral effect, however, is to stymie basic science, the foundational research that underlies new medical treatments. Everything is commodified in the economic cold war with China, including the struggle to find a cure for cancer.

Behind the investigation that led to Wu’s exit—and other such probes across the country—is the National Institutes of Health, in coordination with the FBI. “Even something that is in the fundamental research space, that’s absolutely not classified, has an intrinsic value,” says Lawrence Tabak, principal deputy director of the NIH, explaining his approach. “This pre-patented material is the antecedent to creating intellectual property. In essence, what you’re doing is stealing other people’s ideas.”

More here.

The song “

The song “ People have always disagreed about politics, passionately and sometimes even violently. But in certain historical moments these disagreements were distributed without strong correlations, so that any one political party would contain a variety of views. In a representative democracy, that kind of distribution makes it easier to accomplish things. In contrast, today we see strong political polarization: members of any one party tend to line up with each other on a range of issues, and correspondingly view the other party with deep distrust. Political commentator Ezra Klein has seen this shift in action, and has studied it carefully in his new book

People have always disagreed about politics, passionately and sometimes even violently. But in certain historical moments these disagreements were distributed without strong correlations, so that any one political party would contain a variety of views. In a representative democracy, that kind of distribution makes it easier to accomplish things. In contrast, today we see strong political polarization: members of any one party tend to line up with each other on a range of issues, and correspondingly view the other party with deep distrust. Political commentator Ezra Klein has seen this shift in action, and has studied it carefully in his new book  Scientist and scholar Eric Toner, quoted above in an excerpt from a Friday interview with the business-news channel CNBC, explained that China’s efforts to contain the current outbreak of a fast-moving upper-respiratory illness are “unlikely to be effective.”

Scientist and scholar Eric Toner, quoted above in an excerpt from a Friday interview with the business-news channel CNBC, explained that China’s efforts to contain the current outbreak of a fast-moving upper-respiratory illness are “unlikely to be effective.” To those living in nations not yet consumed by fire, flood, or frost, we can report that for the most part, life seems to go on pretty much as it always has. There are some slight adjustments to be made. The morning routine now begins by checking the news to see which of the hundred or so fires raging out of control across the coast have joined forces to become super-fires, and which of these super-fires have united to become mega-fires. Time between breakfast and the daily commute might well be put aside to send text messages to friends and relatives closest to the hundred or so blazes lately listed as “out of control,” or whose last known location is in danger of immolation. Keeping tabs on where the destruction is taking place is made easier by an app called “Fires Near Me” which sends you an alert when any major fires are moving into your preselected “Watch Zones.” It has become commonplace for social gatherings to end with someone glancing down at their phone and exclaiming “Oh dear, the fires are coming round my place, I better be off.”

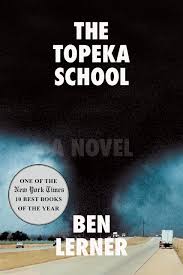

To those living in nations not yet consumed by fire, flood, or frost, we can report that for the most part, life seems to go on pretty much as it always has. There are some slight adjustments to be made. The morning routine now begins by checking the news to see which of the hundred or so fires raging out of control across the coast have joined forces to become super-fires, and which of these super-fires have united to become mega-fires. Time between breakfast and the daily commute might well be put aside to send text messages to friends and relatives closest to the hundred or so blazes lately listed as “out of control,” or whose last known location is in danger of immolation. Keeping tabs on where the destruction is taking place is made easier by an app called “Fires Near Me” which sends you an alert when any major fires are moving into your preselected “Watch Zones.” It has become commonplace for social gatherings to end with someone glancing down at their phone and exclaiming “Oh dear, the fires are coming round my place, I better be off.” Perhaps no figure better illustrates the style and stakes of the hatred of literature, as it has filtered from academia into contemporary literary culture, than the American author Ben Lerner. Lerner, recently described in the New York Times as “the most talented writer of his generation,” was known for advertising his suspicion of aesthetic experience even before he published a book called The Hatred of Poetry in 2016. “I had long worried that I was incapable of having a profound experience of art,” says Adam Gordon, the college-age narrator of Lerner’s 2011 debut novel Leaving the Atocha Station, upon encountering a man crying before a painting at a museum in Madrid, “and I had trouble believing that anyone had. … I was intensely suspicious of people who claimed a poem or painting or piece of music ‘changed their life.’”

Perhaps no figure better illustrates the style and stakes of the hatred of literature, as it has filtered from academia into contemporary literary culture, than the American author Ben Lerner. Lerner, recently described in the New York Times as “the most talented writer of his generation,” was known for advertising his suspicion of aesthetic experience even before he published a book called The Hatred of Poetry in 2016. “I had long worried that I was incapable of having a profound experience of art,” says Adam Gordon, the college-age narrator of Lerner’s 2011 debut novel Leaving the Atocha Station, upon encountering a man crying before a painting at a museum in Madrid, “and I had trouble believing that anyone had. … I was intensely suspicious of people who claimed a poem or painting or piece of music ‘changed their life.’” In November 1942, the German composer Karl Amadeus Hartmann traveled to Vienna from his home in Munich to spend an intense week of study with Anton Webern. The 37-year-old Hartmann was hardly a novice, but the opportunity to work with one of the masters of Viennese modernism (and a highly sought after pedagogue, at that) was too good to let pass. Hartmann could not have imagined, however, prior to his journey, just what kind of an outcast Webern had become. The Nazis had branded him a degenerate and proscribed his music, his finances were a shambles, and he was finding it increasingly difficult to compose. Indeed, with the exception of a single piece, the luminous Cantata No. 2, which he had already begun but would not complete for another year, Webern had by that point completed everything that he ever would. Upon arriving at Webern’s apartment in the suburb of Maria Enzersdorf, Hartmann discovered, much to his surprise, that he happened to be the composer’s only pupil.

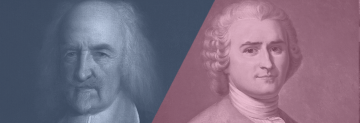

In November 1942, the German composer Karl Amadeus Hartmann traveled to Vienna from his home in Munich to spend an intense week of study with Anton Webern. The 37-year-old Hartmann was hardly a novice, but the opportunity to work with one of the masters of Viennese modernism (and a highly sought after pedagogue, at that) was too good to let pass. Hartmann could not have imagined, however, prior to his journey, just what kind of an outcast Webern had become. The Nazis had branded him a degenerate and proscribed his music, his finances were a shambles, and he was finding it increasingly difficult to compose. Indeed, with the exception of a single piece, the luminous Cantata No. 2, which he had already begun but would not complete for another year, Webern had by that point completed everything that he ever would. Upon arriving at Webern’s apartment in the suburb of Maria Enzersdorf, Hartmann discovered, much to his surprise, that he happened to be the composer’s only pupil. In 1651, Thomas Hobbes famously wrote that life in the state of nature – that is, our natural condition outside the authority of a political state – is ‘solitary, poore, nasty brutish, and short.’ Just over a century later, Jean-Jacques Rousseau countered that human nature is essentially good, and that we could have lived peaceful and happy lives well before the development of anything like the modern state. At first glance, then, Hobbes and Rousseau represent opposing poles in answer to one of the age-old questions of human nature: are we naturally good or evil? In fact, their actual positions are both more complicated and interesting than this stark dichotomy suggests. But why, if at all, should we even think about human nature in these terms, and what can returning to this philosophical debate tell us about how to evaluate the political world we inhabit today?

In 1651, Thomas Hobbes famously wrote that life in the state of nature – that is, our natural condition outside the authority of a political state – is ‘solitary, poore, nasty brutish, and short.’ Just over a century later, Jean-Jacques Rousseau countered that human nature is essentially good, and that we could have lived peaceful and happy lives well before the development of anything like the modern state. At first glance, then, Hobbes and Rousseau represent opposing poles in answer to one of the age-old questions of human nature: are we naturally good or evil? In fact, their actual positions are both more complicated and interesting than this stark dichotomy suggests. But why, if at all, should we even think about human nature in these terms, and what can returning to this philosophical debate tell us about how to evaluate the political world we inhabit today? Science doesn’t usually take after fairy tales. But Rumpelstiltskin, the magical imp who spun straw into gold, would be impressed with the latest chemical wizardry. Researchers at Rice University report today in Nature that they can

Science doesn’t usually take after fairy tales. But Rumpelstiltskin, the magical imp who spun straw into gold, would be impressed with the latest chemical wizardry. Researchers at Rice University report today in Nature that they can  Suppose that you are angry on Tuesday because I stole from you on Monday. Suppose that on Wednesday I return what I stole; I compensate you for any disadvantage occasioned by your not having had it for two days; I offer additional gifts to show my good will; I apologize for my theft as a moment of weakness; and, finally, I promise never to do it again. Suppose, in addition, that you believe my apology is sincere and that I will keep my promise.

Suppose that you are angry on Tuesday because I stole from you on Monday. Suppose that on Wednesday I return what I stole; I compensate you for any disadvantage occasioned by your not having had it for two days; I offer additional gifts to show my good will; I apologize for my theft as a moment of weakness; and, finally, I promise never to do it again. Suppose, in addition, that you believe my apology is sincere and that I will keep my promise. Consider two classic hypotheses about the development of language and cognition.

Consider two classic hypotheses about the development of language and cognition. A team of Italian researchers have strengthened the case that at least the cranium found near Pompeii 100 years ago really does belong to Pliny the Elder, a Roman military leader and polymath who perished while leading a rescue mission following the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 C.E. However, a jawbone that had been found with the skull evidently belonged to somebody else.

A team of Italian researchers have strengthened the case that at least the cranium found near Pompeii 100 years ago really does belong to Pliny the Elder, a Roman military leader and polymath who perished while leading a rescue mission following the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 C.E. However, a jawbone that had been found with the skull evidently belonged to somebody else. In 2001, when I was the new Washington correspondent for The Arizona Republic, I attended the annual awards dinner of the National Immigration Forum. The forum is a left-right coalition that lobbies for unauthorized immigrants and expansive immigration policies. Its board has included officials of the National Council of La Raza, the American Civil Liberties Union and the American Immigration Lawyers Association, as well as the United States Chamber of Commerce, the National Restaurant Association and the American Nursery and Landscape Association.

In 2001, when I was the new Washington correspondent for The Arizona Republic, I attended the annual awards dinner of the National Immigration Forum. The forum is a left-right coalition that lobbies for unauthorized immigrants and expansive immigration policies. Its board has included officials of the National Council of La Raza, the American Civil Liberties Union and the American Immigration Lawyers Association, as well as the United States Chamber of Commerce, the National Restaurant Association and the American Nursery and Landscape Association.