Aparna Kapadia in Scroll.in:

Aparna Kapadia in Scroll.in:

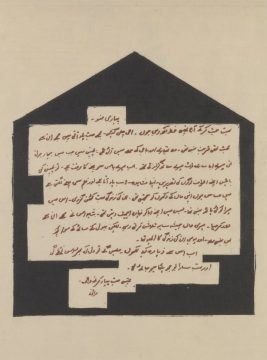

In India, some of the earliest printed recipe books became popular in the 19th century and were written for Anglo-Indians, the term used for the British settled there. While recipes were recorded in the precolonial era, these were in manuscript form, their production and use restricted to very elite, mostly royal settings. Even then, unlike our contemporary cookbooks, entire books containing only recipes, were rare: the late 15th-century Persian work Nimatnama from the Malwa sultanate and Supa Shastra or Science of Cooking, composed around the same period by a Jain king from the present-day Karnataka region, are some known examples of collections that contain recipes for food as well as aphrodisiacs and health potions.

Prescriptions for what people could and should eat as also recipes were more often assimilated into texts produced for broader purposes. For instance, the 16th-century work, Ain-i-Akbari, is primarily a record of Mughal emperor Akbar’s administration. But this compendium also contains sections on the management of various branches of the imperial kitchens and describes recipes that range from simple everyday items like khichdi and saag or greens and richer dishes including a saffron infused lamb biryani and halwa made in ghee. The Emperor, it seems, liked to oversee the management of every part of his empire.

More here.

Cate Lineberry over at Smithsonian Magazine:

Cate Lineberry over at Smithsonian Magazine:

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the TRACERx project had recruited 760 people with early-stage lung cancer. After a person is diagnosed with a primary lung tumour, it is surgically removed and the cells are analysed to reconstruct the tumour’s evolutionary history. Each individual receives a computed tomography (CT) scan every year for five years to check whether their cancer has returned. If there is no sign of relapse, they are discharged and deemed to have been cured. People with later-stage tumours (stages 2 and 3) are offered chemotherapy following surgery to improve the chance of remission or cure.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the TRACERx project had recruited 760 people with early-stage lung cancer. After a person is diagnosed with a primary lung tumour, it is surgically removed and the cells are analysed to reconstruct the tumour’s evolutionary history. Each individual receives a computed tomography (CT) scan every year for five years to check whether their cancer has returned. If there is no sign of relapse, they are discharged and deemed to have been cured. People with later-stage tumours (stages 2 and 3) are offered chemotherapy following surgery to improve the chance of remission or cure.

When I was a child, my brother and I played a computer game based on the Indiana Jones movie franchise. In the course of his adventures, Indy would sometimes come to a delicate impasse that required tact and nuance to resolve. Some adversary was blocking his path to a relic or treasure (including, oddly enough, one of Plato’s lost dialogues), and he needed to say just the right thing to get past them and on to the next challenge. The game offered players a selection of five or so sentences to choose from. The world would sit there in 8-bit paralysis and wait while we pondered how to make it do what we wanted. Press enter on the right sentence and pixelated Indy would sail through. Choose something inapt and game over.

When I was a child, my brother and I played a computer game based on the Indiana Jones movie franchise. In the course of his adventures, Indy would sometimes come to a delicate impasse that required tact and nuance to resolve. Some adversary was blocking his path to a relic or treasure (including, oddly enough, one of Plato’s lost dialogues), and he needed to say just the right thing to get past them and on to the next challenge. The game offered players a selection of five or so sentences to choose from. The world would sit there in 8-bit paralysis and wait while we pondered how to make it do what we wanted. Press enter on the right sentence and pixelated Indy would sail through. Choose something inapt and game over. What they are understanding is that this coronavirus “has such a diversity of effects on so many different organs, it keeps us up at night,” said Thomas McGinn, deputy physician in chief at Northwell Health and director of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. “It’s amazing how many different ways it affects the body.”

What they are understanding is that this coronavirus “has such a diversity of effects on so many different organs, it keeps us up at night,” said Thomas McGinn, deputy physician in chief at Northwell Health and director of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. “It’s amazing how many different ways it affects the body.” When I migrated from Cambridge to my new post at Pembroke College Oxford in the fall of 1969 I got the sense that many of the Old Guard there regarded me as some kind of foreign usurper. Perhaps their own favourite pupils had not been offered the job as they undoubtedly deserved. An exception was Peter Strawson, who was always friendly, and whom I came to admire greatly. Some years later when I belonged to a rather grubby photography workshop in the city I persuaded him to come downtown for me to make a portrait of him. I hope that some of the affection I felt comes through, as well as his undoubted amusement at the occasion.

When I migrated from Cambridge to my new post at Pembroke College Oxford in the fall of 1969 I got the sense that many of the Old Guard there regarded me as some kind of foreign usurper. Perhaps their own favourite pupils had not been offered the job as they undoubtedly deserved. An exception was Peter Strawson, who was always friendly, and whom I came to admire greatly. Some years later when I belonged to a rather grubby photography workshop in the city I persuaded him to come downtown for me to make a portrait of him. I hope that some of the affection I felt comes through, as well as his undoubted amusement at the occasion. In 1977, the poet Adrienne Rich exhorted a graduating class of young women to think of education

In 1977, the poet Adrienne Rich exhorted a graduating class of young women to think of education  Arising by most accounts in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the novel of ideas reflects the challenge posed by the integration of externally developed concepts long before the arrival of conceptual art. Although the novel’s verbal medium would seem to make it intrinsically suited to the endeavor, the mission of presenting “ideas” seems to have pushed a genre famous for its versatility toward a surprisingly limited repertoire of techniques. These came to obtrude against a set of generic expectations—nondidactic representation; a dynamic, temporally complex relation between events and the representation of events; character development; verisimilitude—established only in wake of the novel’s separation from history and romance at the start of the nineteenth century. Compared to these and even older, ancient genres like drama and lyric, the novel is astonishingly young, which is perhaps why departures from its still only freshly consolidated conventions seem especially noticeable.

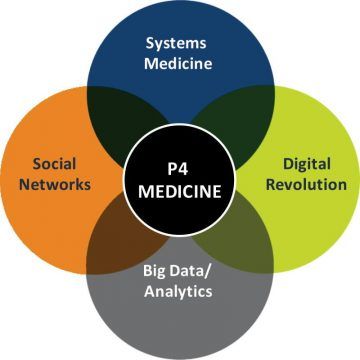

Arising by most accounts in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the novel of ideas reflects the challenge posed by the integration of externally developed concepts long before the arrival of conceptual art. Although the novel’s verbal medium would seem to make it intrinsically suited to the endeavor, the mission of presenting “ideas” seems to have pushed a genre famous for its versatility toward a surprisingly limited repertoire of techniques. These came to obtrude against a set of generic expectations—nondidactic representation; a dynamic, temporally complex relation between events and the representation of events; character development; verisimilitude—established only in wake of the novel’s separation from history and romance at the start of the nineteenth century. Compared to these and even older, ancient genres like drama and lyric, the novel is astonishingly young, which is perhaps why departures from its still only freshly consolidated conventions seem especially noticeable. The highlights of Leroy Hood’s scientific career are like peaks in a mountain range spanning diverse fields, from molecular immunology and engineering, to genomics, to systems medicine. But Hood doesn’t think his trailblazing approach should be unusual, emphasizing that “one of the really key things about science is every 10 or 15 years, you really make a dramatic break and do something new… and you have to learn a lot before you can make fundamental contributions.”

The highlights of Leroy Hood’s scientific career are like peaks in a mountain range spanning diverse fields, from molecular immunology and engineering, to genomics, to systems medicine. But Hood doesn’t think his trailblazing approach should be unusual, emphasizing that “one of the really key things about science is every 10 or 15 years, you really make a dramatic break and do something new… and you have to learn a lot before you can make fundamental contributions.” The term “

The term “ We know from every disaster movie that time is supposed to accelerate, not stand still, during a catastrophe. If asked to draw a scenario months ago, most of us would have imagined moments of chaos and disorder, akin to the profound social chaos in Florence during the plague as described by Boccaccio in his 14th-century work The Decameron, “all respect for the laws of God and man … broken down.”

We know from every disaster movie that time is supposed to accelerate, not stand still, during a catastrophe. If asked to draw a scenario months ago, most of us would have imagined moments of chaos and disorder, akin to the profound social chaos in Florence during the plague as described by Boccaccio in his 14th-century work The Decameron, “all respect for the laws of God and man … broken down.” Sudden, radical transformations of substances known to humanity for eons, like water freezing and soup steaming over a fire, remained mysterious until well into the 20th century. Scientists observed that substances typically change gradually: Heat a collection of atoms a little, and it expands a little. But nudge a material past a critical point, and it becomes something else entirely.

Sudden, radical transformations of substances known to humanity for eons, like water freezing and soup steaming over a fire, remained mysterious until well into the 20th century. Scientists observed that substances typically change gradually: Heat a collection of atoms a little, and it expands a little. But nudge a material past a critical point, and it becomes something else entirely. Scientism – the belief that science is the only valid source of knowledge and that all legitimate questions can be answered by science – is what spawns pseudoscience and science denialism. If science is treated as though it not only informs us but also dictates how our lives ought to be lived and how society ought to be run, then it is easier to peddle in the baseless denial of scientific claims than it is to challenge the illegitimate claim of authority over our choices made on science’s behalf.

Scientism – the belief that science is the only valid source of knowledge and that all legitimate questions can be answered by science – is what spawns pseudoscience and science denialism. If science is treated as though it not only informs us but also dictates how our lives ought to be lived and how society ought to be run, then it is easier to peddle in the baseless denial of scientific claims than it is to challenge the illegitimate claim of authority over our choices made on science’s behalf.