Category: Archives

Education, unchained

James Brooke-Smith in Aeon:

James Brooke-Smith in Aeon:

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Émile; or On Education (1762) is perhaps the most influential work on education written in the modern world. Rousseau’s advocacy of learning via direct experience and creative play inspired the Swiss educational reformer Johann Pestalozzi, the German educator Friedrich Fröbel and the kindergarten movement. His stress on the training of the body as well as the mind was the forerunner of the mania for organised sports that swept English boarding schools in the 19th century and inspired Baron Pierre de Coubertin to found the modern Olympic Games in 1896. His observation that children develop via a series of clearly demarcated stages, each with its own unique cognitive and emotional capacities, underpinned the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s theories of child psychology in the 1920s. And his insistence on the value of learning in nature lies in the background of today’s Forest School movement.

And yet Rousseau referred to his text as ‘less an educational treatise than a visionary’s reveries about education’. Émile is a thought experiment, in which the philosopher imagines a system of education designed to protect the natural unity of his pupil’s consciousness from the ills of civilisation. Rousseau was renowned for being optimistic about human nature. In the primeval forests of our species’ infancy, mankind was solitary, happy and good – a zen-like noble savage who lived entirely for himself and in the present moment. It was only over time, Rousseau argued, as social bonds were extended and civilisation grew more complex, that this original unity was disturbed.

More here.

Donald Trump’s Other Bunker

Peter Nicholas in The Atlantic:

One person who’s unlikely to fall ill at Donald Trump’s Tulsa rally is Donald Trump. When jubilant supporters peel off their masks and whoop their approval as he torches Joe Biden, rest assured that the president will be a safe distance from any pathogens spat into the air. It’s the crowd that’s at the most risk. Trump’s arrival at the BOK Center on Saturday plunks him into the safest of spaces. Security measures will minimize his exposure to the coronavirus. Adoring crowds will gratify a craving for recognition. Attention paid to his first rally in three months could give his flagging campaign a needed jolt. Tulsa, then, amounts to a salve for a president who needs one.

One person who’s unlikely to fall ill at Donald Trump’s Tulsa rally is Donald Trump. When jubilant supporters peel off their masks and whoop their approval as he torches Joe Biden, rest assured that the president will be a safe distance from any pathogens spat into the air. It’s the crowd that’s at the most risk. Trump’s arrival at the BOK Center on Saturday plunks him into the safest of spaces. Security measures will minimize his exposure to the coronavirus. Adoring crowds will gratify a craving for recognition. Attention paid to his first rally in three months could give his flagging campaign a needed jolt. Tulsa, then, amounts to a salve for a president who needs one.

Someone’s bound to get sick, as Trump knows. Rallies posed public-health dangers when he called them off in March, and not much has changed since. At least two members of his coronavirus task force, Anthony Fauci and Deborah Birx, have privately cautioned him that large crowds are a vehicle for transmitting the disease, said an administration official who, like others I talked with for this story, requested anonymity in order to speak candidly. Even Trump conceded in an interview with The Wall Street Journal that some people watching his performance might contract the virus—“a very small percentage.”

Anyone who catches the disease will have sacrificed their health for the televised illusion that Trump is in control, the virus is in retreat, and the country is back to normal, when in fact cases are hitting record highs in Oklahoma and elsewhere and millions of people are out of work. Trump’s team is expecting the 19,000-seat arena to be full, a campaign spokesperson told me, with attendees packed shoulder to shoulder. They’ll be getting temperature checks at the door, and the campaign will offer masks. But many will likely decline, taking cues from a president who refuses to wear a mask in public or acknowledge either his own vulnerability or the epic crisis that happened on his watch.

Of course, Trump has that luxury.

More here.

The message is clear: Policing in America is broken and must change

Emily Bazelon in The New York Times:

On Memorial Day, the police in Minneapolis killed George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man. Three officers stood by or assisted as a fourth, Derek Chauvin, pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck for more than eight minutes. Floyd said he could not breathe and then became unresponsive. His death has touched off the largest and most sustained round of protests the country has seen since the 1960s, as well as demonstrations around the world. The killing has also prompted renewed calls to address brutality, racial disparities and impunity in American policing — and beyond that, to change the conditions that burden black and Latino communities.

On Memorial Day, the police in Minneapolis killed George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man. Three officers stood by or assisted as a fourth, Derek Chauvin, pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck for more than eight minutes. Floyd said he could not breathe and then became unresponsive. His death has touched off the largest and most sustained round of protests the country has seen since the 1960s, as well as demonstrations around the world. The killing has also prompted renewed calls to address brutality, racial disparities and impunity in American policing — and beyond that, to change the conditions that burden black and Latino communities.

The search for transformation has a long and halting history. In 1967, the Kerner Commission, appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to investigate the causes of uprisings and rioting that year, recommended ways to improve the relationship between the police and black communities, but in the end it entrenched law enforcement as a means of social control. “Neighborhood police stations were installed inside public-housing projects in the very spaces vacated by community-action programs,” writes the Yale historian Elizabeth Hinton, author of “From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime.” In 1992, after the acquittals of three Los Angeles police officers who savagely beat Rodney King on camera, unrest erupted in the city. The police were ill prepared, and more than 50 people died. In 1994, Congress gave the Justice Department the authority to investigate a pattern or practice of policing that violated civil rights protections.

Since 2013, the Black Lives Matter movement has made police violence a pressing national and local issue and helped lead to the election of officials — including the district attorneys in several major metropolitan areas — who have tried to make the police more accountable for misconduct and sought to decrease incarceration. The killing of George Floyd in police custody shows how far the country has to go; the resulting protests have pushed the Minneapolis City Council to take the previously unthinkable step of pledging to dismantle its Police Department. But what does that mean, and what should other cities do? We brought together five experts and organizers to talk about how to change policing in America in the context of broader concerns about systemic racism and inequality.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Mi Skin

my skin my cast iron skin my equator skin my cast iron equator skin my skin my scarring skin my grey scarring skin my grey skin my asylum seeker skin my skin my colorblind skin my smoke skin my color smoke skin is burning my burning skin my cursed skin my cursed skin is burning my skin my prayer skin my prayer marshmallow skin my cloud marshmallow skin my burning cloud skin my skin my marshmallow skin is burning my skin my unreeled skin bare my bare unreeled skin my capitulate skin my skin my blues skin my limpid skin my limpid blues skin my skin my blues is burning skin & my skin is a home my rust skin my skin rusts my rust skin is burning

oxidizes

my skin oxidizes my neutral skin my black neutral skin my pinched off black neutral skin is burning my picked skin my dry skin my dry skin is burning my matured skin my matured skin is laundered skin my laundered skin is skin my becoming skin my malleable becoming skin my language skin is malleable my skin is burning my miracle skin my annotation skin my annotation miracle skin my mirror skin my splinter skin my mirror splinter skin my magic conjuring skin my #blackboymagic skin my black skin is conjuring skin and boys are burning

by Dean Bowen

from: Bokman

publisher: Jurgen Maas, Amsterdam, 2018

translation: Dean Bowen

first published on Poetry International, 2020

Original, after “Read More”

The Mystical Dreams of Descartes

‘The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again’ by M John Harrison

Olivia Laing at The Guardian:

Towards the end of the last century, there was a spate of haunted London novels, by Iain Sinclair, Peter Ackroyd and Chris Petit among others. Broadly psychogeographic in nature, they featured middle-aged men washed up on the outer reaches of the Thames, part of the detritus of a city ravaged by Thatcherism. In 1989, the science fiction writer M John Harrison took this mood and drove it out of London, crash-landing in the Yorkshire hills with the magnificently unsettling Climbers, a novel about an unhappy exile named Mike struggling to keep his footing among a group of temerarious local climbers.

Towards the end of the last century, there was a spate of haunted London novels, by Iain Sinclair, Peter Ackroyd and Chris Petit among others. Broadly psychogeographic in nature, they featured middle-aged men washed up on the outer reaches of the Thames, part of the detritus of a city ravaged by Thatcherism. In 1989, the science fiction writer M John Harrison took this mood and drove it out of London, crash-landing in the Yorkshire hills with the magnificently unsettling Climbers, a novel about an unhappy exile named Mike struggling to keep his footing among a group of temerarious local climbers.

Harrison described this real, gritty world with the same precise and estranging fluency with which he has more often mapped galactic space, using the dense idiolect of climbing to make atmosphere and geology resonate on an emotional, interior level.

more here.

The Literature of Hervé Guibert

Parul Seghal at the NYT:

Anonymity comes for us all soon enough, but it has encroached with mystifying speed upon the French writer Hervé Guibert, who died at 36 in 1991. His work has been strangely neglected in the Anglophone world, never mind its innovation and historical importance, its breathtaking indiscretion, tenderness and gore. How can an artist so original, so thrillingly indifferent to convention and the tyranny of good taste — let alone one so prescient — remain untranslated and unread?

Anonymity comes for us all soon enough, but it has encroached with mystifying speed upon the French writer Hervé Guibert, who died at 36 in 1991. His work has been strangely neglected in the Anglophone world, never mind its innovation and historical importance, its breathtaking indiscretion, tenderness and gore. How can an artist so original, so thrillingly indifferent to convention and the tyranny of good taste — let alone one so prescient — remain untranslated and unread?

Happily his extensive, idiosyncratic body of work is being slowly exhumed, and freshly translated. His journals are now available in English, along with his memoirs, including “Crazy for Vincent,” an account of his obsession with a young skateboarder, mostly straight, who served as his reluctant muse.

more here.

Friday, June 19, 2020

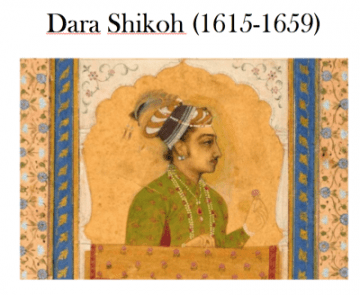

The History of Philosophy in Global Context: Three Case Studies

Justin E. H. Smith in his own blog:

For Hegel, the Greek miracle lay in the separating out of mythology and philosophy, so that the articulation of questions about, say, the nature of time, could be addressed in a universal idiom that would not presuppose the existence of Chronos as a divine personification of time. For the ancient Persians, by contrast, to use Hegel’s own example, reflection on the nature of time could only proceed through culturally embedded narratives inseparable from religion and lore.

For Hegel, the Greek miracle lay in the separating out of mythology and philosophy, so that the articulation of questions about, say, the nature of time, could be addressed in a universal idiom that would not presuppose the existence of Chronos as a divine personification of time. For the ancient Persians, by contrast, to use Hegel’s own example, reflection on the nature of time could only proceed through culturally embedded narratives inseparable from religion and lore.

Thus for Hegel only those expressions of philosophy that descend from the Greeks have any claim to universality, and thus only these expressions deserve to be exported from their place of origin throughout the world. This 19th-century Europeanisation of philosophy witnessed the destruction of millennia-old disciplinary divisions in India and China, notably, as newly subjugated institutions of learning rushed to model their curricula on those of European universities, creating neologisms for “philosophy” where these had not existed before.

More here.

Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann’s classic lecture on curved space

Michael Lucibella at the website of the American Physical Society:

Albert Einstein changed our view of the universe in 1915 when he published the general theory of relativity, in which he set forth the notion of a four-dimensional spacetime that warps and curves in response to mass or energy. The geometric foundation for his work was laid some 60 years earlier, with the work of a German mathematician named Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann.

Albert Einstein changed our view of the universe in 1915 when he published the general theory of relativity, in which he set forth the notion of a four-dimensional spacetime that warps and curves in response to mass or energy. The geometric foundation for his work was laid some 60 years earlier, with the work of a German mathematician named Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann.

Born in what is now the Federal Republic of Germany in 1826, Riemann was the second of six children of a Lutheran pastor, who taught his son until he turned ten. The young Riemann was shy and nervous, but gifted in mathematics–so much so that while attending high school in Hannover, his knowledge sometimes surpassed that of his teachers. In 1846, his father scraped together sufficient funds to send his son to the University of Göttingen, where Riemann initially intended to study theology so that he could help support his family. But then he attended lectures by Carl Friedrich Gauss and Moritz Stern, who inspired him to switch his studies. With his parents’ blessing, Riemann transferred to the University of Berlin the following year, studying under some of the most prominent mathematicians of his time.

More here.

Albert Memmi’s About-Face

Editor’s Note: Albert Memmi died recently, this is an insightful article from 2007.

Lisa Lieberman in the Michigan Quarterly Review:

In The Colonizer and the Colonized (1957) Albert Memmi remarked that “the benevolent colonizer can never attain the good, for his only choice is not between good and evil, but between evil and uneasiness.” Evil and uneasiness are a fair description of the choices faced by Leah Shakdiel, an Israeli peace activist featured in the documentary Can You Hear Me?: Israeli and Palestinian Women Fight for Peace. Born in a house that once belonged to Arabs, she rejected the crusading Zionism of her parents, choosing instead to live in a small town in the Negev desert and to work for social justice. But in order to visit her daughter, who lives in a West Bank settlement, she must travel on what she calls an “apartheid road”—a highway open only to Israelis; her daughter’s decision, Shakdiel confesses to the filmmaker, makes her feel like a failure as a mother. All the same, she loves her daughter. What can she do?

In The Colonizer and the Colonized (1957) Albert Memmi remarked that “the benevolent colonizer can never attain the good, for his only choice is not between good and evil, but between evil and uneasiness.” Evil and uneasiness are a fair description of the choices faced by Leah Shakdiel, an Israeli peace activist featured in the documentary Can You Hear Me?: Israeli and Palestinian Women Fight for Peace. Born in a house that once belonged to Arabs, she rejected the crusading Zionism of her parents, choosing instead to live in a small town in the Negev desert and to work for social justice. But in order to visit her daughter, who lives in a West Bank settlement, she must travel on what she calls an “apartheid road”—a highway open only to Israelis; her daughter’s decision, Shakdiel confesses to the filmmaker, makes her feel like a failure as a mother. All the same, she loves her daughter. What can she do?

More here.

Nicolas Cage’s Acting: Is It Deep or Dumb?

Josephine Miles: “Cage”

Don Bogen at Poetry Magazine:

What stuck me about “Cage” when I first saw it among the previously uncollected work in Josephine Miles’ Collected Poems 1930-83 was its lyricism. Although Miles wrote lyric poetry all her life, she is generally recognized as a poet more engaged with speech and ideas than with song. Her interest in the American vernacular, from people yelling at each other in traffic to bureaucratic jargon, informs her most well-known pieces. These include thoughtful observations on academic life in Berkeley, where she was a professor from the 1940s through the 1970s (no poet is better on teaching and learning); explorations of philosophical paradoxes; quirky takes on neighborhood life; and clear-eyed portraits of a childhood marked by the arthritis that would leave her disabled—all with her distinctive qualities of concision, wry humor, and an ear for the way people talk. But “Cage” evinces a strand in her work that has largely been overlooked, something more song-like and emotional.

What stuck me about “Cage” when I first saw it among the previously uncollected work in Josephine Miles’ Collected Poems 1930-83 was its lyricism. Although Miles wrote lyric poetry all her life, she is generally recognized as a poet more engaged with speech and ideas than with song. Her interest in the American vernacular, from people yelling at each other in traffic to bureaucratic jargon, informs her most well-known pieces. These include thoughtful observations on academic life in Berkeley, where she was a professor from the 1940s through the 1970s (no poet is better on teaching and learning); explorations of philosophical paradoxes; quirky takes on neighborhood life; and clear-eyed portraits of a childhood marked by the arthritis that would leave her disabled—all with her distinctive qualities of concision, wry humor, and an ear for the way people talk. But “Cage” evinces a strand in her work that has largely been overlooked, something more song-like and emotional.

more here.

Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic

Sailing to Byzantium read by Dermot Crowley

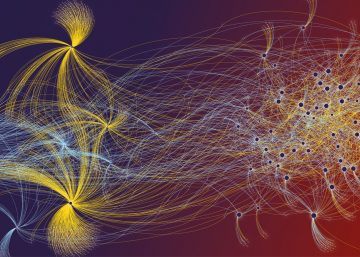

A new breed of researcher is turning to computation to understand society — and then change it

Heidi Ledford in Nature:

Elizaveta Sivak spent nearly a decade training as a sociologist. Then, in the middle of a research project, she realized that she needed to head back to school.

Elizaveta Sivak spent nearly a decade training as a sociologist. Then, in the middle of a research project, she realized that she needed to head back to school.

Sivak studies families and childhood at the National Research University Higher School of Economics in Moscow. In 2015, she studied the movements of adolescents by asking them in a series of interviews to recount ten places that they had visited in the past five days. A year later, she had analysed the data and was feeling frustrated by the narrowness of relying on individual interviews, when a colleague pointed her to a paper analysing data from the Copenhagen Networks Study, a ground-breaking project that tracked the social-media contacts, demographics and location of about 1,000 students, with five-minute resolution, over five months1. She knew then that her field was about to change. “I realized that these new kinds of data will revolutionize social science forever,” she says. “And I thought that it’s really cool.”

With that, Sivak decided to learn how to program, and join the revolution. Now, she and other computational social scientists are exploring massive and unruly data sets, extracting meaning from society’s digital imprint. They are tracking people’s online activities; exploring digitized books and historical documents; interpreting data from wearable sensors that record a person’s every step and contact; conducting online surveys and experiments that collect millions of data points; and probing databases that are so large that they will yield secrets about society only with the help of sophisticated data analysis.

More here.

Roberts Wanted Minimal Competence, but Trump Couldn’t Deliver

Adam Serwer in The Atlantic:

Two years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts gave the Trump administration a very important piece of advice: When you come to the Supreme Court, you need to do your homework. In his majority opinion sanctioning the Trump administration’s travel ban, Roberts disregarded Trump’s public statements that “Islam hates us,” and that America has problems “with Muslims coming into the country,” because the ultimate text of the travel ban issued by the administration “says nothing about religion.” Rather, Roberts wrote, the ban “reflects the results of a worldwide review process undertaken by multiple Cabinet officials and their agencies.” At the time, I found it shocking that the chief justice was essentially telling the Trump administration that it could turn the president’s prejudices into public policy with adequate lawyering and sufficient legal pretext. I assumed that the administration would do the necessary work of providing pretenses for its decisions, in order to achieve the policy outcome it desired. What I did not expect was that the Trump administration would not even bother to do that much.

Two years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts gave the Trump administration a very important piece of advice: When you come to the Supreme Court, you need to do your homework. In his majority opinion sanctioning the Trump administration’s travel ban, Roberts disregarded Trump’s public statements that “Islam hates us,” and that America has problems “with Muslims coming into the country,” because the ultimate text of the travel ban issued by the administration “says nothing about religion.” Rather, Roberts wrote, the ban “reflects the results of a worldwide review process undertaken by multiple Cabinet officials and their agencies.” At the time, I found it shocking that the chief justice was essentially telling the Trump administration that it could turn the president’s prejudices into public policy with adequate lawyering and sufficient legal pretext. I assumed that the administration would do the necessary work of providing pretenses for its decisions, in order to achieve the policy outcome it desired. What I did not expect was that the Trump administration would not even bother to do that much.

On Thursday, Roberts joined with the four Democratic appointees on the Court to invalidate the Trump administration’s decision to repeal the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, which has shielded about 700,000 undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children from deportation. The decision states that the Trump administration has the power to rescind the policy, but that the “arbitrary and capricious” manner in which it did so violated the Administrative Procedure Act, which governs decisions made by government agencies. The Department of Homeland Security, Roberts writes, was obliged to consider all of its options before repealing DACA wholesale. “Making that difficult decision was the agency’s job,” Roberts argues, “but the agency failed to do it.”

More here.

Friday Poem

These words of two, three years ago returned.

— Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, tr. by Will Petersen

Laughter

one day, Coyote sees Duck walking her ducklings,

Coyote asks her how she keeps them in a straight line,

Duck says she sews them together

with white horsetail hair every morning

and tugs on the line gently,

until the horsehair disappears,

that is how she keeps her ducklings in a row

as usual, Coyote leaves smiling, she sees a white horse

grazing in a nearby field,

she plucks a few strands of tail hair

and returns to her burrow

the next morning, one by one

she begins to sew her pups together

when she finishes, she gently tugs on the horsehair

and drags their little bodies along the ground,

Coyote tilts her head in dismay and becomes distraught,

she realizes she has killed her little pups

“Indians” will laugh about anything and anyone,

no matter the tragedy

by Chrisosto Apache

from Poetry

June , 2018

Thursday, June 18, 2020

The Intellectual Vocation

Joshua P. Hochschild in First Things:

Once upon a time, education was rhetorical training. Learning to think well, and thereby to negotiate all of life with responsible intelligence, was fundamentally about interacting with—drawing from and contributing to—a fund of powerful writing. But then, to make a long story short, things got complicated, “rhetoric” was demoted to one department among many, and that department was eventually rebranded as “Communication Studies.” In what could serve as a tragic epilogue to the history of Western education, young Mattie, son of the title character in Wendell Berry’s Hannah Coulter, goes off to study communication and becomes unable to talk to his own parents. “Communication of what?” asks Hannah’s husband, Nathan. “God knows what,” answers Hannah. “And that was about the extent of our conversation on that subject.”

Once upon a time, education was rhetorical training. Learning to think well, and thereby to negotiate all of life with responsible intelligence, was fundamentally about interacting with—drawing from and contributing to—a fund of powerful writing. But then, to make a long story short, things got complicated, “rhetoric” was demoted to one department among many, and that department was eventually rebranded as “Communication Studies.” In what could serve as a tragic epilogue to the history of Western education, young Mattie, son of the title character in Wendell Berry’s Hannah Coulter, goes off to study communication and becomes unable to talk to his own parents. “Communication of what?” asks Hannah’s husband, Nathan. “God knows what,” answers Hannah. “And that was about the extent of our conversation on that subject.”

It’s no surprise what Mattie missed in college. Anything like traditional rhetorical education is by now rare and usually accidental, and while some of us still try to keep alive a classical conception of “liberal education,” we sense a need for new rhetorical resources to capture what that is. Three new books about thinking testify that the old learning is ever-renewing, and available to anyone who knows what to look for.

Scott Newstok’s How to Think Like Shakespeare directly addresses rhetoric as “the craft of future discourse,” and attends to the particular practices that cultivate this craft.

More here.

René Girard – Violence and Religion