Bill O’Neil in PLOS Biology:

The pathologist makes do with red wine until an effective drug is available, the biochemist discards the bread from her sandwiches, and the mathematician indulges in designer chocolate with a clear conscience. The demographer sticks to vitamin supplements, and while the evolutionary biologist calculates the compensations of celibacy, the population biologist transplants gonads, but so far only those of his laboratory mice. Their common cause is to control and extend the healthy lifespan of humans. They want to cure ageing and the diseases that come with it.

The pathologist makes do with red wine until an effective drug is available, the biochemist discards the bread from her sandwiches, and the mathematician indulges in designer chocolate with a clear conscience. The demographer sticks to vitamin supplements, and while the evolutionary biologist calculates the compensations of celibacy, the population biologist transplants gonads, but so far only those of his laboratory mice. Their common cause is to control and extend the healthy lifespan of humans. They want to cure ageing and the diseases that come with it.

…Extending Life

Although the life-enhancing effects of Sinclair’s polyphenols are so far confined to the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the work suggests that researchers are only one small step from making a giant leap for humankind. “People imagined that it might have been possible, but few people thought that it was going to be possible so quickly to find such things,” says Sinclair. The field of ageing research is buzzing. Resveratrol stimulated a known activator of increased longevity in yeast, the enzyme Sir-2, and thereby extended the organism’s lifespan by 70% (Box 1). Sir-2 belongs to a family of proteins with members in higher organisms, including SIR-2.1, an enzyme that regulates lifespan in worms, and SIRT-1, the human enzyme that promotes cell survival (Figure 1). Though researchers still do not know whether SIRT-1, or “Sir-2 in humans,” as Sinclair puts it, has anything to do with longevity, there is a good chance that it does, judging by its pedigree. In any event, resveratrol proved to be a potent activator of the human enzyme. This might not be altogether surprising, at least not now, given that the polyphenol is already associated with health benefits in humans, notably the mitigation of such age-related defects as neurodegeneration, carcinogenesis, and atherosclerosis.

More here.

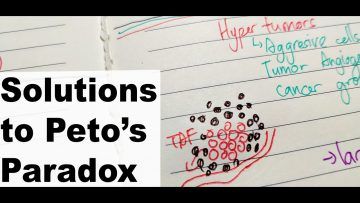

Larger organisms have more potentially carcinogenic cells, tend to live longer and require more ontogenic cell divisions. Therefore, intuitively one might expect cancer incidence to scale with body size. Evidence from mammals, however, suggests that the cancer risk does not correlate with body size. This observation defines “Peto’s paradox.”

Larger organisms have more potentially carcinogenic cells, tend to live longer and require more ontogenic cell divisions. Therefore, intuitively one might expect cancer incidence to scale with body size. Evidence from mammals, however, suggests that the cancer risk does not correlate with body size. This observation defines “Peto’s paradox.” What brings me back to a painting is often a feeling, like a nagging muscle memory, of wanting not only to see, but to sense the painting’s facture. At the Met, I always return to Degas’s Portrait of a Woman in Gray (c. 1865), and the strange way in which the sitter’s black scarf seems to dominate the picture. Looking in closely, to the point where the weave of the canvas is visible and catching against the streaks of thinned oil, I find my wrist twitching with the desire to repeat the artist’s marks, anticipating the slight give of the fabric against the brushstroke, the soft friction of the bristles as they run out of pigment. It follows that my eyes’ movements are bound by this black shape that blends into the woman’s bonnet and resembles a figure holding an umbrella against the wind or wielding a scythe high in the air. Other portions of the painting seem secondary—the sketched-in right hand, the unfinished left eye—the whole composition just scaffolding for this burst of gesture. The tugging at my wrist lasts well after I leave the picture, each tightening of my fingers against the imaginary brush pulling the scarf back into focus.

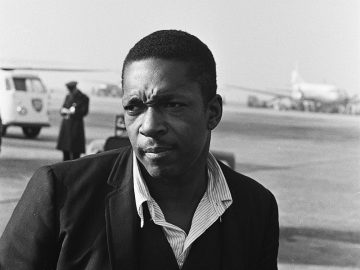

What brings me back to a painting is often a feeling, like a nagging muscle memory, of wanting not only to see, but to sense the painting’s facture. At the Met, I always return to Degas’s Portrait of a Woman in Gray (c. 1865), and the strange way in which the sitter’s black scarf seems to dominate the picture. Looking in closely, to the point where the weave of the canvas is visible and catching against the streaks of thinned oil, I find my wrist twitching with the desire to repeat the artist’s marks, anticipating the slight give of the fabric against the brushstroke, the soft friction of the bristles as they run out of pigment. It follows that my eyes’ movements are bound by this black shape that blends into the woman’s bonnet and resembles a figure holding an umbrella against the wind or wielding a scythe high in the air. Other portions of the painting seem secondary—the sketched-in right hand, the unfinished left eye—the whole composition just scaffolding for this burst of gesture. The tugging at my wrist lasts well after I leave the picture, each tightening of my fingers against the imaginary brush pulling the scarf back into focus. The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground. Though many in the U.S. are disoriented and disheartened by the lack of an effective federal response to the coronavirus pandemic, John Dewey, an American philosopher, psychologist and educator, would not have been surprised.

Though many in the U.S. are disoriented and disheartened by the lack of an effective federal response to the coronavirus pandemic, John Dewey, an American philosopher, psychologist and educator, would not have been surprised. This is not the right time for a bigger particle accelerator. But

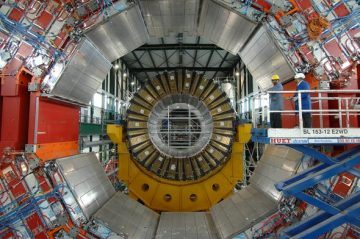

This is not the right time for a bigger particle accelerator. But

Khurram Hussain’s Islam as Critique: Sayyid Ahmad Khan and the Challenge of Modernity is an important and highly original book. At one level, the book is a fresh reading of some of Sayyid Aḥmad Khān’s (d. 1898) most profound intellectual contributions. At another, more important (at least for this reader) level, the book is an elaborate set of reflections on the place of Islam in the West and the place of (the study of) Islamic thought in modernity. The book’s offerings are daring and original, and the style is engaging. There are, inevitably, given the ambition of the project’s claims and the size of the book, areas in which one wishes the book offered a fuller discussion. Similarly, given the bold and very timely nature of the arguments, there are many venues that call for engagement to which we can and should respond. Thus, the book is obvious interest to scholars of South Asian Islam, Islamic thought, and broadly anyone concerned with the crises of modernity and alternative ways of being in the world, which, ideally, should be everyone.

Khurram Hussain’s Islam as Critique: Sayyid Ahmad Khan and the Challenge of Modernity is an important and highly original book. At one level, the book is a fresh reading of some of Sayyid Aḥmad Khān’s (d. 1898) most profound intellectual contributions. At another, more important (at least for this reader) level, the book is an elaborate set of reflections on the place of Islam in the West and the place of (the study of) Islamic thought in modernity. The book’s offerings are daring and original, and the style is engaging. There are, inevitably, given the ambition of the project’s claims and the size of the book, areas in which one wishes the book offered a fuller discussion. Similarly, given the bold and very timely nature of the arguments, there are many venues that call for engagement to which we can and should respond. Thus, the book is obvious interest to scholars of South Asian Islam, Islamic thought, and broadly anyone concerned with the crises of modernity and alternative ways of being in the world, which, ideally, should be everyone. It is perhaps no surprise that such changes in the behavior of human beings, labeled a

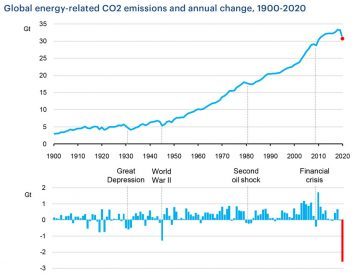

It is perhaps no surprise that such changes in the behavior of human beings, labeled a  The long era of European imperialism started in the 15th century but it was roughly 400 years before the land grab turned to Africa. As late as 1870, outsiders controlled only about 10 percent of the continent. But then a confluence of forces opened the door: The need for raw materials, the demand for new markets for finished goods, and medical advances that made it possible for Europeans to survive in the tropics. By the 1880s, the “Scramble for Africa” had begun. At the heart of this rapacious quest was the Congo River in equatorial Africa and its enormous, almost impenetrable, rain forest. Today, this part of Africa includes the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and the Central African Republic. In “Land of Tears: The Exploration and Exploitation of Equatorial Africa,” Yale University Professor Robert Harms deftly and authoritatively recounts the region’s compelling, fascinating, appalling, and tragic history.

The long era of European imperialism started in the 15th century but it was roughly 400 years before the land grab turned to Africa. As late as 1870, outsiders controlled only about 10 percent of the continent. But then a confluence of forces opened the door: The need for raw materials, the demand for new markets for finished goods, and medical advances that made it possible for Europeans to survive in the tropics. By the 1880s, the “Scramble for Africa” had begun. At the heart of this rapacious quest was the Congo River in equatorial Africa and its enormous, almost impenetrable, rain forest. Today, this part of Africa includes the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and the Central African Republic. In “Land of Tears: The Exploration and Exploitation of Equatorial Africa,” Yale University Professor Robert Harms deftly and authoritatively recounts the region’s compelling, fascinating, appalling, and tragic history. Moshe Behar in Contending Modernities:

Moshe Behar in Contending Modernities: Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB: