Mark Mazower in The New York Review of Books:

When Eric Hobsbawm died in 2012 at the age of ninety-five, he was probably the best-known historian in the English-speaking world. His books have been translated into every major language (and numerous minor ones), and many of them have remained continuously in print since their first appearance. Though his work centered on the history of labor, he wrote with equal fluency about the crisis of the seventeenth century and the bandits of Eritrea, the standard of living during the industrial revolution and Billie Holiday’s blues. For range and accessibility, there was no one to touch him. What he gave his readers was above all the sense of being intellectually alive, of the sheer excitement of a fresh idea and a bold, unsentimental argument. The works themselves are his memorial. What is there to learn from his biography?

Historians lead for the most part pretty dull lives: if they make it big enough to warrant a biography of their own, it is unlikely to feature anything more exciting than endless conferences, gripes about publishers, and the eventual bestowal of honors. Readers do not generally care about infighting in academia. Nor is it easy to be gripped by the more important but largely abstract questions of intellectual argument and debate that articulate positions and create schools of thought. In Hobsbawm’s case, however, the scale and nature of his achievement raise questions of their own. How do we explain his vast readership? How did a Marxist historian achieve such success during socialism’s decline in the second half of the twentieth century?

More here.

Perhaps the most groundbreaking discoveries of recent years have been in genetic history. It has already been several decades since the study of DNA revealed how little substance there was to claims of racial difference. Study of genetic material found in ancient bones also suggests that, rather than a single migration out of Africa, humans populated the globe in waves that intermingled, coming back as well as going forwards. “We weren’t migrants once in the distant past and then again in the most recent era,” Shah writes. “We’ve been migrants all along.”

Perhaps the most groundbreaking discoveries of recent years have been in genetic history. It has already been several decades since the study of DNA revealed how little substance there was to claims of racial difference. Study of genetic material found in ancient bones also suggests that, rather than a single migration out of Africa, humans populated the globe in waves that intermingled, coming back as well as going forwards. “We weren’t migrants once in the distant past and then again in the most recent era,” Shah writes. “We’ve been migrants all along.” Angela said she had read Cusk’s newest book on the plane over. It slowly dawned on her that the essays in that collection contemplate a variety of ostracisms: from being given the silent treatment by one’s own parents to the exclusion of women writers from the literary canon. Aftermath, Medea, the Outline trilogy – they’re all about being cast out into the wilderness. In an essay called ‘Coventry’ Cusk characterises such exile as ‘ejection from the story’. The only thing to do once you’re ‘living amidst the waste and shattered buildings, the desecrated past’ is to search ‘for whatever truth might be found amid the smoking ruins’.

Angela said she had read Cusk’s newest book on the plane over. It slowly dawned on her that the essays in that collection contemplate a variety of ostracisms: from being given the silent treatment by one’s own parents to the exclusion of women writers from the literary canon. Aftermath, Medea, the Outline trilogy – they’re all about being cast out into the wilderness. In an essay called ‘Coventry’ Cusk characterises such exile as ‘ejection from the story’. The only thing to do once you’re ‘living amidst the waste and shattered buildings, the desecrated past’ is to search ‘for whatever truth might be found amid the smoking ruins’. As a philosopher turned GP myself,

As a philosopher turned GP myself,  Kuhn, who has written before about white working-class Americans, builds his book on long-ago police records and witness statements to recreate in painful detail a May day of rage, menace and blood. Antiwar demonstrators had massed at Federal Hall and other Lower Manhattan locations, only to be set upon brutally, and cravenly, by hundreds of steamfitters, ironworkers, plumbers and other laborers from nearby construction sites like the nascent World Trade Center. Many of those men had served in past wars and viscerally despised the protesters as a bunch of pampered, longhaired, draft-dodging, flag-desecrating snotnoses.

Kuhn, who has written before about white working-class Americans, builds his book on long-ago police records and witness statements to recreate in painful detail a May day of rage, menace and blood. Antiwar demonstrators had massed at Federal Hall and other Lower Manhattan locations, only to be set upon brutally, and cravenly, by hundreds of steamfitters, ironworkers, plumbers and other laborers from nearby construction sites like the nascent World Trade Center. Many of those men had served in past wars and viscerally despised the protesters as a bunch of pampered, longhaired, draft-dodging, flag-desecrating snotnoses. Megha Majumdar’s polyphonic debut novel,

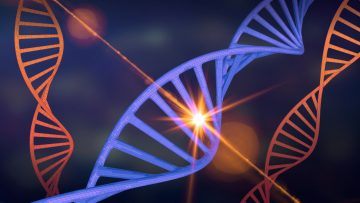

Megha Majumdar’s polyphonic debut novel,  If you could shrink small enough to descend the genetic helix of any animal, plant, fungus, bacterium or virus on Earth as though it were a spiral staircase, you would always find yourself turning right — never left. It’s a universal trait in want of an explanation.

If you could shrink small enough to descend the genetic helix of any animal, plant, fungus, bacterium or virus on Earth as though it were a spiral staircase, you would always find yourself turning right — never left. It’s a universal trait in want of an explanation. Annexation looks like the executioner of the two-state solution. Israel has changed the facts on the ground, with the rapid growth of settlements rendering that goal less and less viable. But the declaration of sovereignty over parts of the occupied territories, in putting a formal seal on physical realities, will be a new and terrible moment, and above all a fresh injustice to Palestinians.

Annexation looks like the executioner of the two-state solution. Israel has changed the facts on the ground, with the rapid growth of settlements rendering that goal less and less viable. But the declaration of sovereignty over parts of the occupied territories, in putting a formal seal on physical realities, will be a new and terrible moment, and above all a fresh injustice to Palestinians. T

T

The second-worst thing about cancer chairs is that they are attached to televisions. Someone somewhere is always at war with silence. It’s impossible to read, so I answer email, or watch some cop drama on my computer, or, if it seems unavoidable, explore the lives of my nurses. A trip to Cozumel with old girlfriends, a costume party with political overtones, an advanced degree on the internet: they’re all the same, these lives, which is to say that the nurses tell me nothing, perhaps because amid the din and pain it’s impossible to say anything of substance, or perhaps because they know that nothing is precisely what we both expect. It’s the very currency of the place. Perhaps they are being excruciatingly candid.

The second-worst thing about cancer chairs is that they are attached to televisions. Someone somewhere is always at war with silence. It’s impossible to read, so I answer email, or watch some cop drama on my computer, or, if it seems unavoidable, explore the lives of my nurses. A trip to Cozumel with old girlfriends, a costume party with political overtones, an advanced degree on the internet: they’re all the same, these lives, which is to say that the nurses tell me nothing, perhaps because amid the din and pain it’s impossible to say anything of substance, or perhaps because they know that nothing is precisely what we both expect. It’s the very currency of the place. Perhaps they are being excruciatingly candid. In 2005, Barry Marshall, an Australian gastroenterologist and researcher, shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery that peptic ulcers are caused not by stress, as was commonly thought, but by a bacterium called

In 2005, Barry Marshall, an Australian gastroenterologist and researcher, shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery that peptic ulcers are caused not by stress, as was commonly thought, but by a bacterium called  In his new book, The Drunken Silenus,

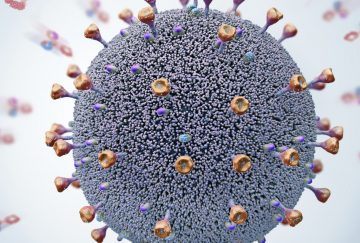

In his new book, The Drunken Silenus,  A pair of studies published this week is shedding light on the duration of immunity following COVID-19, showing patients lose their IgG antibodies—the virus-specific, slower-forming antibodies associated with long-term immunity—within weeks or months after recovery. With COVID-19, most people who become infected do

A pair of studies published this week is shedding light on the duration of immunity following COVID-19, showing patients lose their IgG antibodies—the virus-specific, slower-forming antibodies associated with long-term immunity—within weeks or months after recovery. With COVID-19, most people who become infected do