Category: Archives

The Racist Roots of New Technology

Stephen Kearse at The Nation:

The modern study of the intersection of race and technology has its roots in the 1990s, when tech utopianism clashed with the racism of tech culture. As the Internet grew into a massive nexus for commerce and leisure and became the heart of modern industry, the ills of tech workplaces manifested themselves online in chat rooms, message boards, and multiplayer video games that were rife with harassment and hate speech. Documenting these instances, a range of scholars, activists, and politicians attempted to combat these ills, but with little success. When the Simon Wiesenthal Center sent letters to Internet providers in 1996 protesting the rise of neo-Nazi websites, for example, the reply it received from a representative of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a prominent tech lobby, channeled a now commonplace mantra: “The best response is always to answer bad speech with more speech.” Similarly, media studies researcher Lisa Nakamura documented a dismissive comment in a study of the online game LambdaMOO. In response to a failed community petition to curb racial harassment, a detractor countered, “Well, who knows my race unless I tell them? If race isn’t important [then] why mention it? If you want to get in somebody’s face with your race then perhaps you deserve a bit of flak.”

The modern study of the intersection of race and technology has its roots in the 1990s, when tech utopianism clashed with the racism of tech culture. As the Internet grew into a massive nexus for commerce and leisure and became the heart of modern industry, the ills of tech workplaces manifested themselves online in chat rooms, message boards, and multiplayer video games that were rife with harassment and hate speech. Documenting these instances, a range of scholars, activists, and politicians attempted to combat these ills, but with little success. When the Simon Wiesenthal Center sent letters to Internet providers in 1996 protesting the rise of neo-Nazi websites, for example, the reply it received from a representative of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a prominent tech lobby, channeled a now commonplace mantra: “The best response is always to answer bad speech with more speech.” Similarly, media studies researcher Lisa Nakamura documented a dismissive comment in a study of the online game LambdaMOO. In response to a failed community petition to curb racial harassment, a detractor countered, “Well, who knows my race unless I tell them? If race isn’t important [then] why mention it? If you want to get in somebody’s face with your race then perhaps you deserve a bit of flak.”

more here.

The Unruly Genius of Joyce Carol Oates

Leo Robson at The New Yorker:

Oates’s friend the novelist John Gardner once suggested that she try writing a story “in which things go well, for a change.” That hasn’t happened yet. Her latest book, the enormous and frequently brilliant “Night. Sleep. Death. The Stars.” (Ecco)—the forty-ninth novel she has published, if you exclude the ones she has written under pseudonyms—is a characteristic work. It begins with an act of police brutality, and proceeds to document the multifarious consequences for the victim’s wife and children: alcoholism, low-level criminality, marital breakdown, incipient nervous collapse. In a 1977 journal entry, Oates acknowledged that her work turns instinctively toward what she called “the central, centralizing act of violence that seems to symbolize something beyond itself.” Perhaps the most heavily ironic statement in her œuvre comes in her second novel, “A Garden of Earthly Delights” (1967), when a woman says, “Nobody killed nobody, this is the United States,” while the most characteristic piece of exposition may be found in “Little Bird of Heaven” (2009): “Daddy was bringing me home on that November evening not long before his death-by-firing-squad to a house from which he’d been banished by my mother.”

Oates’s friend the novelist John Gardner once suggested that she try writing a story “in which things go well, for a change.” That hasn’t happened yet. Her latest book, the enormous and frequently brilliant “Night. Sleep. Death. The Stars.” (Ecco)—the forty-ninth novel she has published, if you exclude the ones she has written under pseudonyms—is a characteristic work. It begins with an act of police brutality, and proceeds to document the multifarious consequences for the victim’s wife and children: alcoholism, low-level criminality, marital breakdown, incipient nervous collapse. In a 1977 journal entry, Oates acknowledged that her work turns instinctively toward what she called “the central, centralizing act of violence that seems to symbolize something beyond itself.” Perhaps the most heavily ironic statement in her œuvre comes in her second novel, “A Garden of Earthly Delights” (1967), when a woman says, “Nobody killed nobody, this is the United States,” while the most characteristic piece of exposition may be found in “Little Bird of Heaven” (2009): “Daddy was bringing me home on that November evening not long before his death-by-firing-squad to a house from which he’d been banished by my mother.”

more here.

The History of Zero

Nils-Bertin Wallin in YaleGlobal Online:

The Sumerians were the first to develop a counting system to keep an account of their stock of goods – cattle, horses, and donkeys, for example. The Sumerian system was positional; that is, the placement of a particular symbol relative to others denoted its value. The Sumerian system was handed down to the Akkadians around 2500 BC and then to the Babylonians in 2000 BC. It was the Babylonians who first conceived of a mark to signify that a number was absent from a column; just as 0 in 1025 signifies that there are no hundreds in that number. Although zero’s Babylonian ancestor was a good start, it would still be centuries before the symbol as we know it appeared.

The Sumerians were the first to develop a counting system to keep an account of their stock of goods – cattle, horses, and donkeys, for example. The Sumerian system was positional; that is, the placement of a particular symbol relative to others denoted its value. The Sumerian system was handed down to the Akkadians around 2500 BC and then to the Babylonians in 2000 BC. It was the Babylonians who first conceived of a mark to signify that a number was absent from a column; just as 0 in 1025 signifies that there are no hundreds in that number. Although zero’s Babylonian ancestor was a good start, it would still be centuries before the symbol as we know it appeared.

The renowned mathematicians among the Ancient Greeks, who learned the fundamentals of their math from the Egyptians, did not have a name for zero, nor did their system feature a placeholder as did the Babylonian. They may have pondered it, but there is no conclusive evidence to say the symbol even existed in their language. It was the Indians who began to understand zero both as a symbol and as an idea.

Brahmagupta, around 650 AD, was the first to formalize arithmetic operations using zero. He used dots underneath numbers to indicate a zero. These dots were alternately referred to as ‘sunya’, which means empty, or ‘kha’, which means place. Brahmagupta wrote standard rules for reaching zero through addition and subtraction as well as the results of operations with zero. The only error in his rules was division by zero, which would have to wait for Isaac Newton and G.W. Leibniz to tackle.

But it would still be a few centuries before zero reached Europe. First, the great Arabian voyagers would bring the texts of Brahmagupta and his colleagues back from India along with spices and other exotic items. Zero reached Baghdad by 773 AD and would be developed in the Middle East by Arabian mathematicians who would base their numbers on the Indian system. In the ninth century, Mohammed ibn-Musa al-Khowarizmi was the first to work on equations that equaled zero, or algebra as it has come to be known. He also developed quick methods for multiplying and dividing numbers known as algorithms (a corruption of his name). Al-Khowarizmi called zero ‘sifr’, from which our cipher is derived. By 879 AD, zero was written almost as we now know it, an oval – but in this case smaller than the other numbers. And thanks to the conquest of Spain by the Moors, zero finally reached Europe; by the middle of the twelfth century, translations of Al-Khowarizmi’s work had weaved their way to England.

More here.

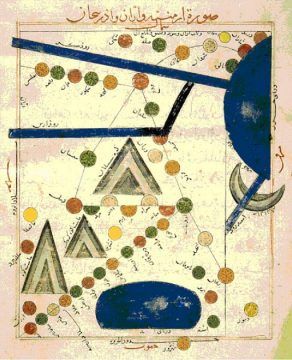

Contribution of Al-Khwarizmi to Mathematics and Geography

N. Akmal Ayyubi in Muslim Heritage:

One of the greatest minds of the early mathematical production in Arabic was Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (b. before 800, d. after 847 in Baghdad) who was a mathematician and astronomer as well as a geographer and a historian. It is said that he is the author in Arabic of one of the oldest astronomical tables, of one the oldest works on arithmetic and the oldest work on algebra; some of his scientific contributions were translated into Latin and were used until the 16th century as the principal mathematical textbooks in European universities. Originally he belonged to Khwârazm (modern Khiwa) situated in Turkistan but he carried on his scientific career in Baghdad and all his works are in Arabic.

One of the greatest minds of the early mathematical production in Arabic was Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (b. before 800, d. after 847 in Baghdad) who was a mathematician and astronomer as well as a geographer and a historian. It is said that he is the author in Arabic of one of the oldest astronomical tables, of one the oldest works on arithmetic and the oldest work on algebra; some of his scientific contributions were translated into Latin and were used until the 16th century as the principal mathematical textbooks in European universities. Originally he belonged to Khwârazm (modern Khiwa) situated in Turkistan but he carried on his scientific career in Baghdad and all his works are in Arabic.

He was summoned to Baghdad by Abbasid Caliph Al-Ma’mun (213-833), who was a patron of knowledge and learning. Al-Ma’mun established the famous Bayt al-Hikma (House of Wisdom) which worked on the model of a library and a research academy. It had a large and rich library (Khizânat Kutub al-Hikma) and distinguished scholars of various faiths were assembled to produce scientific masterpieces as well as to translate faithfully nearly all the great and important ancient works of Greek, Sanskrit, Pahlavi and of other languages into Arabic. Muhammad al-Khwarizmi, according to Ibn al-Nadîm [1] and Ibn al-Qiftî [2] (and as it is quoted by the late Aydin Sayili) [3], was attached to (or devoted himself entirely to) Khizânat al-Hikma. It is also said that he was appointed court astronomer of Caliph Al-Ma’mun who also commissioned him to prepare abstracts from one of the Indian books entitled Surya Siddhanta which was called al-Sindhind [4] in Arabic [5]. Al-Khwarizmi’s name is linked to the translation into Arabic of certain Greek works [6] and he also produced his own scholarly works not only on astronomy and mathematics but also in geography and history. It was for Caliph al-Ma’mun that Al-Khwarizmi composed his astronomical treatise and dedicated his book on Algebra.

…It is worth remarking that the term al-jabr, in the Latinized form of algebra, has found its way into the modern languages, whilst the old mathematical term algorism is a distortion of al-Khwarizmi’s name.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Bag

I Lost My Medicine Bag

from back when I believed

in magic. It’s made from a doe’s stomach

and holds grizzly teeth and claw,

stones from Tibet and the moon

the garden and the beach

where the baby’s ashes are buried.

Now I expect this bag to cure my illnesses—

I can’t walk and the skin on my back

pulses and moans without a mouth.

The gods exiled me to this loneliness

of pain for their own good reasons.

by Jim Harrison

from Dead Man’s Float

Copper Canyon Press, 2015

Sunday, June 28, 2020

Grace Must Come for the Debased and Unworthy

Morgan Meis in Church Life Journal:

Jan Rubens was in love, and then he was on the run. Once the affair with Anna of Saxony was discovered and Jan was arrested, he ran back to his wife, Peter Paul’s mother, begging her for forgiveness and for help. Who knows what was in the man’s heart? Maybe the whole ordeal created deep within the soul of Jan Rubens a love of his wife that had never existed before. Maybe the fog of love was lifted from his eyes, the fog of lust cleared away and gone too was the clouding monomania that sets in when a married man runs into the arms of another woman. Maybe one passion had overtaken the mind of Jan Rubens as he fell into this desperate affair with Anna of Saxony, an otherwise difficult woman as the contemporary sources say, and it made him forget about the rest of the world. He started to see everything through the lens of this clawing need, the need to be with Anna of Saxony, the need to manufacture more and more reasons that he spend time with her, work on projects with her, center his life around her. This became a demanding and unforgiving logic. He stopped asking why, he stopped considering his life in any other light than the light of need. He needed to be with Anna of Saxony, dearest Anna, the only woman alive.

Jan Rubens was in love, and then he was on the run. Once the affair with Anna of Saxony was discovered and Jan was arrested, he ran back to his wife, Peter Paul’s mother, begging her for forgiveness and for help. Who knows what was in the man’s heart? Maybe the whole ordeal created deep within the soul of Jan Rubens a love of his wife that had never existed before. Maybe the fog of love was lifted from his eyes, the fog of lust cleared away and gone too was the clouding monomania that sets in when a married man runs into the arms of another woman. Maybe one passion had overtaken the mind of Jan Rubens as he fell into this desperate affair with Anna of Saxony, an otherwise difficult woman as the contemporary sources say, and it made him forget about the rest of the world. He started to see everything through the lens of this clawing need, the need to be with Anna of Saxony, the need to manufacture more and more reasons that he spend time with her, work on projects with her, center his life around her. This became a demanding and unforgiving logic. He stopped asking why, he stopped considering his life in any other light than the light of need. He needed to be with Anna of Saxony, dearest Anna, the only woman alive.

More here.

Science denialism is not just a simple matter of logic or ignorance

Adrian Bardon in Scientific American:

Bemoaning uneven individual and state compliance with public health recommendations, top U.S. COVID-19 adviser Anthony Fauci recently blamed the country’s ineffective pandemic response on an American “anti-science bias.” He called this bias “inconceivable,” because “science is truth.” Fauci compared those discounting the importance of masks and social distancing to “anti-vaxxers” in their “amazing” refusal to listen to science.

Bemoaning uneven individual and state compliance with public health recommendations, top U.S. COVID-19 adviser Anthony Fauci recently blamed the country’s ineffective pandemic response on an American “anti-science bias.” He called this bias “inconceivable,” because “science is truth.” Fauci compared those discounting the importance of masks and social distancing to “anti-vaxxers” in their “amazing” refusal to listen to science.

It is Fauci’s profession of amazement that amazes me. As well-versed as he is in the science of the coronavirus, he’s overlooking the well-established science of “anti-science bias,” or science denial.

Americans increasingly exist in highly polarized, informationally insulated ideological communities occupying their own information universes.

More here.

I Love Teaching at Penn State, But Going Back This Fall Is a Mistake

Paul M. Kellermann in Esquire:

According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, 63 percent of American colleges and universities are planning to return to in-person classes this fall, with another 17 percent operating from a hybrid model. This likely comes as welcome news to the millions of undergrads desperate for a return to the college atmosphere—an atmosphere where social distancing is virtually nonexistent, except in situations of weak cell service. In college towns, health care providers are prepping for an onslaught. Faculty and staff, meanwhile, feel abandoned, excluded from the decision-making process as a coterie of VPs weighed financial considerations against health risks. Somehow, no one in the ivory tower’s executive suite bothered to take pedagogic concerns into account—or to consult with those who practice pedagogy professionally.

According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, 63 percent of American colleges and universities are planning to return to in-person classes this fall, with another 17 percent operating from a hybrid model. This likely comes as welcome news to the millions of undergrads desperate for a return to the college atmosphere—an atmosphere where social distancing is virtually nonexistent, except in situations of weak cell service. In college towns, health care providers are prepping for an onslaught. Faculty and staff, meanwhile, feel abandoned, excluded from the decision-making process as a coterie of VPs weighed financial considerations against health risks. Somehow, no one in the ivory tower’s executive suite bothered to take pedagogic concerns into account—or to consult with those who practice pedagogy professionally.

More here.

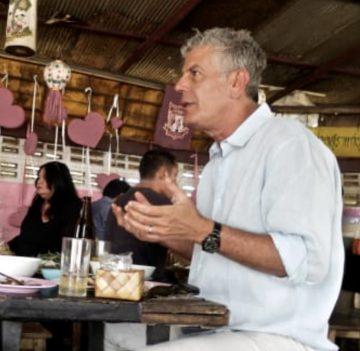

Tattoos, karaoke and a touch of film noir: What it was like to work with Anthony Bourdain in Thailand

Joe Cummings at CNN:

When crew from CNN’s “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown” contacted me in February 2014 to ask for assistance with an upcoming shoot in Thailand, of course I agreed without hesitation.

When crew from CNN’s “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown” contacted me in February 2014 to ask for assistance with an upcoming shoot in Thailand, of course I agreed without hesitation.

No food celebrity was more widely loved than Anthony Bourdain at the time, and his posthumous fame and recognition have only grown since. In an era where chefs are the new rockstars, he was Johnny Cash, keeping it raw and real.

Playing down his history in professional kitchens, including Manhattan’s Brasserie Les Halles, he liked to describe himself as a failed chef and talked openly about past substance abuse. He sharply criticized over-hyped TV chefs and the Michelin cult, using his influence instead to praise the street vendors and line cooks who feed most of the world.

More here.

Dan Foster (1958 – 2020)

Mady Mesplé (1931 – 2020)

Joel Schumacher (1939 – 2020)

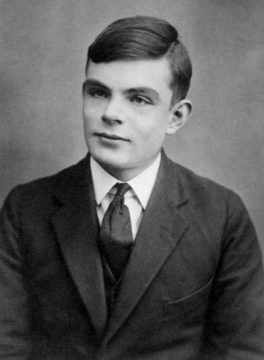

Code-Breaking Computer Scientist

Patti Wigington in ThoughtCo:

Alan Mathison Turing (1912 –1954) was one of England’s foremost mathematicians and computer scientists. Because of his work in artificial intelligence and codebreaking, along with his groundbreaking Enigma machine, he is credited with ending World War II. Turing’s life ended in tragedy. Convicted of “indecency” for his sexual orientation, Turing lost his security clearance, was chemically castrated, and later committed suicide at age 41.

Alan Mathison Turing (1912 –1954) was one of England’s foremost mathematicians and computer scientists. Because of his work in artificial intelligence and codebreaking, along with his groundbreaking Enigma machine, he is credited with ending World War II. Turing’s life ended in tragedy. Convicted of “indecency” for his sexual orientation, Turing lost his security clearance, was chemically castrated, and later committed suicide at age 41.

…During World War II, Bletchley Park was the home base of British Intelligence’s elite codebreaking unit. Turing joined the Government Code and Cypher School and in September 1939, when war with Germany began, reported to Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire for duty. Shortly before Turing’s arrival at Bletchley, Polish intelligence agents had provided the British with information about the German Enigma machine. Polish cryptanalysts had developed a code-breaking machine called the Bomba, but the Bomba became useless in 1940 when German intelligence procedures changed and the Bomba could no longer crack the code. Turing, along with fellow code-breaker Gordon Welchman, got to work building a replica of the Bomba, called the Bombe, which was used to intercept thousands of German messages every month. These broken codes were then relayed to Allied forces, and Turing’s analysis of German naval intelligence allowed the British to keep their convoys of ships away from enemy U-boats.

…In addition to his codebreaking work, Turing is regarded as a pioneer in the field of artificial intelligence. He believed that computers could be taught to think independently of their programmers, and devised the Turing Test to determine whether or not a computer was truly intelligent. The test is designed to evaluate whether the interrogator can figure out which answers come from the computer and which come from a human; if the interrogator can’t tell the difference, then the computer would be considered “intelligent.”

…In 1952, Turing began a romantic relationship with a 19-year-old man named Arnold Murray. During a police investigation into a burglary at Turing’s home, he admitted that he and Murray were involved sexually. Because homosexuality was a crime in England, both men were charged and convicted of “gross indecency.” Turing was given the option of a prison sentence or probation with “chemical treatment” designed to reduce the libido. He chose the latter, and underwent a chemical castration procedure over the next twelve months. The treatment left him impotent and caused him to develop gynecomastia, an abnormal development of breast tissue. In addition, his security clearance was revoked by the British government, and he was no longer permitted to work in the intelligence field. In June 1954, Turing’s housekeeper found him dead. A post-mortem examination determined that he had died of cyanide poisoning, and the inquest ruled his death as suicide. A half-eaten apple was found nearby. The apple was never tested for cyanide, but it was determined to be the most likely method used by Turing.

More here.

Sunday Poem

The Tempest -Excerpt: Act 4, Scene 1

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

William Shakespeare

The History of Artificial Intelligence

Rockwell Anyoha in SITN (Harvard University):

In the first half of the 20th century, science fiction familiarized the world with the concept of artificially intelligent robots. It began with the “heartless” Tin man from the Wizard of Oz and continued with the humanoid robot that impersonated Maria in Metropolis. By the 1950s, we had a generation of scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers with the concept of artificial intelligence (or AI) culturally assimilated in their minds. One such person was Alan Turing, a young British polymath who explored the mathematical possibility of artificial intelligence. Turing suggested that humans use available information as well as reason in order to solve problems and make decisions, so why can’t machines do the same thing? This was the logical framework of his 1950 paper, Computing Machinery and Intelligence in which he discussed how to build intelligent machines and how to test their intelligence.

In the first half of the 20th century, science fiction familiarized the world with the concept of artificially intelligent robots. It began with the “heartless” Tin man from the Wizard of Oz and continued with the humanoid robot that impersonated Maria in Metropolis. By the 1950s, we had a generation of scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers with the concept of artificial intelligence (or AI) culturally assimilated in their minds. One such person was Alan Turing, a young British polymath who explored the mathematical possibility of artificial intelligence. Turing suggested that humans use available information as well as reason in order to solve problems and make decisions, so why can’t machines do the same thing? This was the logical framework of his 1950 paper, Computing Machinery and Intelligence in which he discussed how to build intelligent machines and how to test their intelligence.

Unfortunately, talk is cheap. What stopped Turing from getting to work right then and there? First, computers needed to fundamentally change. Before 1949 computers lacked a key prerequisite for intelligence: they couldn’t store commands, only execute them. In other words, computers could be told what to do but couldn’t remember what they did. Second, computing was extremely expensive. In the early 1950s, the cost of leasing a computer ran up to $200,000 a month. Only prestigious universities and big technology companies could afford to dillydally in these uncharted waters. A proof of concept as well as advocacy from high profile people were needed to persuade funding sources that machine intelligence was worth pursuing.

Five years later, the proof of concept was initialized through Allen Newell, Cliff Shaw, and Herbert Simon’s, Logic Theorist. The Logic Theorist was a program designed to mimic the problem solving skills of a human and was funded by Research and Development (RAND) Corporation. It’s considered by many to be the first artificial intelligence program and was presented at the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (DSRPAI) hosted by John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky in 1956. In this historic conference, McCarthy, imagining a great collaborative effort, brought together top researchers from various fields for an open ended discussion on artificial intelligence, the term which he coined at the very event.

More here.

Saturday, June 27, 2020

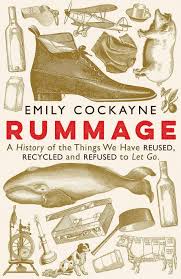

The Joys of Rubbish

Kathryn Hughes at The Guardian:

Above all, Cockayne wants us to revise our assumption that people in the past must have been better at reuse and recycling (not the same thing) than we are today. There is, she insists, “no linear history of improvement”, no golden age when everyone automatically sorted their household scraps and spent their evenings turning swords into ploughshares because they knew it was the right thing to do. Indeed, in the 1530s the more stuff you threw away, the better you were performing your civic duty: refuse and surfeit was built into the semiotics of display in Henry VIII’s England, which explains why, on formal occasions, it was stylish to have claret and white wine running down the gutters. Three generations later and Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarian troops had found new ways to manipulate codes of waste and value. In 1646 they ransacked Winchester cathedral and sent all the precious parchments off to London to be made into kites “withal to fly in the air”.

Above all, Cockayne wants us to revise our assumption that people in the past must have been better at reuse and recycling (not the same thing) than we are today. There is, she insists, “no linear history of improvement”, no golden age when everyone automatically sorted their household scraps and spent their evenings turning swords into ploughshares because they knew it was the right thing to do. Indeed, in the 1530s the more stuff you threw away, the better you were performing your civic duty: refuse and surfeit was built into the semiotics of display in Henry VIII’s England, which explains why, on formal occasions, it was stylish to have claret and white wine running down the gutters. Three generations later and Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarian troops had found new ways to manipulate codes of waste and value. In 1646 they ransacked Winchester cathedral and sent all the precious parchments off to London to be made into kites “withal to fly in the air”.

more here.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson Meets Emily Dickinson

Martha Ackmann at The Atlantic:

Dickinson said her life had not been constrained or dreary in any way. “I find ecstasy in living,” she explained. The “mere sense of living is joy enough.” When at last the opportunity arose, Higginson posed the question he most wanted to ask: Did you ever want a job, have a desire to travel or see people? The question unleashed a forceful reply. “I never thought of conceiving that I could ever have the slightest approach to such a want in all future time.” Then she loaded on more. “I feel that I have not expressed myself strongly enough.” Dickinson reserved her most striking statement for what poetry meant to her, or, rather, how it made her feel. “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me I know that is poetry,” she said. “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way.” Dickinson was remarkable. Brilliant. Candid. Deliberate. Mystifying. After eight years of waiting, Higginson was finally sitting across from Emily Dickinson of Amherst, and all he wanted to do was listen.

Dickinson said her life had not been constrained or dreary in any way. “I find ecstasy in living,” she explained. The “mere sense of living is joy enough.” When at last the opportunity arose, Higginson posed the question he most wanted to ask: Did you ever want a job, have a desire to travel or see people? The question unleashed a forceful reply. “I never thought of conceiving that I could ever have the slightest approach to such a want in all future time.” Then she loaded on more. “I feel that I have not expressed myself strongly enough.” Dickinson reserved her most striking statement for what poetry meant to her, or, rather, how it made her feel. “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me I know that is poetry,” she said. “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way.” Dickinson was remarkable. Brilliant. Candid. Deliberate. Mystifying. After eight years of waiting, Higginson was finally sitting across from Emily Dickinson of Amherst, and all he wanted to do was listen.

more here.

The Shape of Epidemics

S. Jones and Stefan Helmreich in Boston Review (figure from From Kristine Moore et al., “The Future of the COVID-19 Pandemic” (April 30, 2020). Used by Boston Review with permission from the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota):

S. Jones and Stefan Helmreich in Boston Review (figure from From Kristine Moore et al., “The Future of the COVID-19 Pandemic” (April 30, 2020). Used by Boston Review with permission from the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota):

On January 29, just under a month after the first instances of COVID-19 were reported in Wuhan, Chinese health officials published a clinical report about their first 425 cases, describing them as “the first wave of the epidemic.” On March 4 the French epidemiologist Antoine Flahault asked, “Has China just experienced a herald wave, to use terminology borrowed from those who study tsunamis, and is the big wave still to come?” The Asia Times warned shortly thereafter that “a second deadly wave of COVID-19 could crash over China like a tsunami.” A tsunami, however, struck elsewhere, with the epidemic surging in Iran, Italy, France, and then the United States. By the end of April, with the United States having passed one million cases, the wave forecasts had become bleaker. Prominent epidemiologists predicted three possible future “wave scenarios”—described by one Boston reporter as “seascapes,” characterized either by oscillating outbreaks, the arrival of a “monster wave,” or a persistent and rolling crisis.

While this language may be new to much of the public, the figure of the wave has long been employed to describe, analyze, and predict the behavior of epidemics. Understanding this history can help us better appreciate the conceptual inheritances of a scientific discipline suddenly at the center of public discussion. It can also help us judge the utility as well as limitations of those representations of epidemiological waves now in play in thinking about the science and policy of COVID-19. As the statistician Edward Tufte writes in his classic work The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (1983), “At their best, graphics are instruments for reasoning about quantitative information.” The wave, operating as a hybrid of the diagrammatic, mathematical, and pictorial, certainly does help to visualize and think about COVID-19 data, but it also does much more. The wave image has become an instrument for public health management and prediction—even prophecy—offering a synoptic, schematic view of the dynamics it describes.

More here.