Michael Specter in The New Yorker:

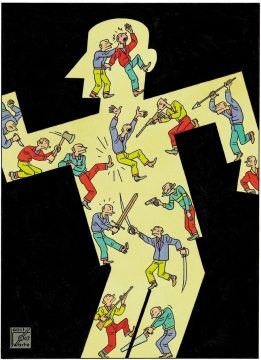

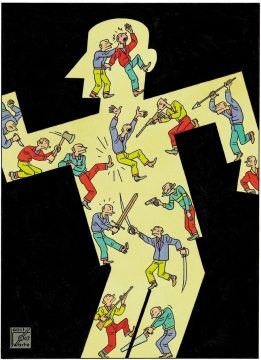

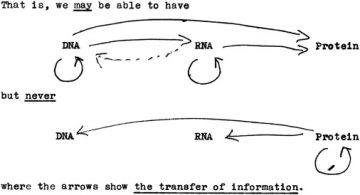

Nothing—not even the Plague—has posed a more persistent threat to humanity than viral diseases: yellow fever, measles, and smallpox have been causing epidemics for thousands of years. At the end of the First World War, fifty million people died of the Spanish flu; smallpox may have killed half a billion during the twentieth century alone. Those viruses were highly infectious, yet their impact was limited by their ferocity: a virus may destroy an entire culture, but if we die it dies, too. As a result, not even smallpox possessed the evolutionary power to influence humans as a species—to alter our genetic structure. That would require an organism to insinuate itself into the critical cells we need in order to reproduce: our germ cells. Only retroviruses, which reverse the usual flow of genetic code from DNA to RNA, are capable of that. A retrovirus stores its genetic information in a single-stranded molecule of RNA, instead of the more common double-stranded DNA. When it infects a cell, the virus deploys a special enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, that enables it to copy itself and then paste its own genes into the new cell’s DNA. It then becomes part of that cell forever; when the cell divides, the virus goes with it. Scientists have long suspected that if a retrovirus happens to infect a human sperm cell or egg, which is rare, and if that embryo survives—which is rarer still—the retrovirus could take its place in the blueprint of our species, passed from mother to child, and from one generation to the next, much like a gene for eye color or asthma.

Nothing—not even the Plague—has posed a more persistent threat to humanity than viral diseases: yellow fever, measles, and smallpox have been causing epidemics for thousands of years. At the end of the First World War, fifty million people died of the Spanish flu; smallpox may have killed half a billion during the twentieth century alone. Those viruses were highly infectious, yet their impact was limited by their ferocity: a virus may destroy an entire culture, but if we die it dies, too. As a result, not even smallpox possessed the evolutionary power to influence humans as a species—to alter our genetic structure. That would require an organism to insinuate itself into the critical cells we need in order to reproduce: our germ cells. Only retroviruses, which reverse the usual flow of genetic code from DNA to RNA, are capable of that. A retrovirus stores its genetic information in a single-stranded molecule of RNA, instead of the more common double-stranded DNA. When it infects a cell, the virus deploys a special enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, that enables it to copy itself and then paste its own genes into the new cell’s DNA. It then becomes part of that cell forever; when the cell divides, the virus goes with it. Scientists have long suspected that if a retrovirus happens to infect a human sperm cell or egg, which is rare, and if that embryo survives—which is rarer still—the retrovirus could take its place in the blueprint of our species, passed from mother to child, and from one generation to the next, much like a gene for eye color or asthma.

When the sequence of the human genome was fully mapped, in 2003, researchers also discovered something they had not anticipated: our bodies are littered with the shards of such retroviruses, fragments of the chemical code from which all genetic material is made. It takes less than two per cent of our genome to create all the proteins necessary for us to live. Eight per cent, however, is composed of broken and disabled retroviruses, which, millions of years ago, managed to embed themselves in the DNA of our ancestors. They are called endogenous retroviruses, because once they infect the DNA of a species they become part of that species. One by one, though, after molecular battles that raged for thousands of generations, they have been defeated by evolution. Like dinosaur bones, these viral fragments are fossils. Instead of having been buried in sand, they reside within each of us, carrying a record that goes back millions of years. Because they no longer seem to serve a purpose or cause harm, these remnants have often been referred to as “junk DNA.” Many still manage to generate proteins, but scientists have never found one that functions properly in humans or that could make us sick.

Then, last year, Thierry Heidmann brought one back to life.

More here.

On Saturday, the residents of Verkhoyansk, Russia, marked the first day of summer with 100 degree Fahrenheit temperatures. Not that they could enjoy it, really, as Verkhoyansk is in Siberia, hundreds of miles from the nearest beach. That’s much, much hotter than towns inside the Arctic Circle usually get. That 100 degrees appears to be a record, well above the average June high temperature of 68 degrees. Yet it’s likely the people of Verkhoyansk will see that record broken again in their lifetimes: The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet—if not faster—creating ecological chaos for the plants and animals that populate the north.

On Saturday, the residents of Verkhoyansk, Russia, marked the first day of summer with 100 degree Fahrenheit temperatures. Not that they could enjoy it, really, as Verkhoyansk is in Siberia, hundreds of miles from the nearest beach. That’s much, much hotter than towns inside the Arctic Circle usually get. That 100 degrees appears to be a record, well above the average June high temperature of 68 degrees. Yet it’s likely the people of Verkhoyansk will see that record broken again in their lifetimes: The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet—if not faster—creating ecological chaos for the plants and animals that populate the north.

In one of the twentieth century’s most memorable scenes from literature, a man is standing on a beach, pulling on a long rope that stretches out to sea. The rope is covered in thick seaweed. He yanks and tugs, and out of the foaming waves comes a horse’s head. It’s black and shiny and lies there at the water’s edge, its dead eyes staring while greenish eels slither from every orifice. The eels crawl out, shiny and entrails-like, more than two dozen of them; when the man has shoved them all into a potato sack, he pries open the horse’s grinning mouth, sticks his hands into its throat, and pulls out two more eels, as thick as his own arms.

In one of the twentieth century’s most memorable scenes from literature, a man is standing on a beach, pulling on a long rope that stretches out to sea. The rope is covered in thick seaweed. He yanks and tugs, and out of the foaming waves comes a horse’s head. It’s black and shiny and lies there at the water’s edge, its dead eyes staring while greenish eels slither from every orifice. The eels crawl out, shiny and entrails-like, more than two dozen of them; when the man has shoved them all into a potato sack, he pries open the horse’s grinning mouth, sticks his hands into its throat, and pulls out two more eels, as thick as his own arms. Until I read Howard Means’s Splash! and Bonnie Tsui’s Why We Swim, my main encounter with the history of the sport had been a Victorian-inspired swimming gala organised by members of my local team at north London’s Parliament Hill Lido. We competed in novelty races that predated the streamlining of swimming into a competitive sport, swimming upright holding umbrellas in one race, wearing blindfolds in another. We jumped into the pool in vintage dresses to see what it was like to swim hampered by heavy fabrics.

Until I read Howard Means’s Splash! and Bonnie Tsui’s Why We Swim, my main encounter with the history of the sport had been a Victorian-inspired swimming gala organised by members of my local team at north London’s Parliament Hill Lido. We competed in novelty races that predated the streamlining of swimming into a competitive sport, swimming upright holding umbrellas in one race, wearing blindfolds in another. We jumped into the pool in vintage dresses to see what it was like to swim hampered by heavy fabrics. Nothing—not even the Plague—has posed a more persistent threat to humanity than viral diseases: yellow fever, measles, and smallpox have been causing epidemics for thousands of years. At the end of the First World War, fifty million people died of the Spanish flu; smallpox may have killed half a billion during the twentieth century alone. Those viruses were highly infectious, yet their impact was limited by their ferocity: a virus may destroy an entire culture, but if we die it dies, too. As a result, not even smallpox possessed the evolutionary power to influence humans as a species—to alter our genetic structure. That would require an organism to insinuate itself into the critical cells we need in order to reproduce: our germ cells. Only retroviruses, which reverse the usual flow of genetic code from DNA to RNA, are capable of that. A retrovirus stores its genetic information in a single-stranded molecule of RNA, instead of the more common double-stranded DNA. When it infects a cell, the virus deploys a special enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, that enables it to copy itself and then paste its own genes into the new cell’s DNA. It then becomes part of that cell forever; when the cell divides, the virus goes with it. Scientists have long suspected that if a retrovirus happens to infect a human sperm cell or egg, which is rare, and if that embryo survives—which is rarer still—the retrovirus could take its place in the blueprint of our species, passed from mother to child, and from one generation to the next, much like a gene for eye color or asthma.

Nothing—not even the Plague—has posed a more persistent threat to humanity than viral diseases: yellow fever, measles, and smallpox have been causing epidemics for thousands of years. At the end of the First World War, fifty million people died of the Spanish flu; smallpox may have killed half a billion during the twentieth century alone. Those viruses were highly infectious, yet their impact was limited by their ferocity: a virus may destroy an entire culture, but if we die it dies, too. As a result, not even smallpox possessed the evolutionary power to influence humans as a species—to alter our genetic structure. That would require an organism to insinuate itself into the critical cells we need in order to reproduce: our germ cells. Only retroviruses, which reverse the usual flow of genetic code from DNA to RNA, are capable of that. A retrovirus stores its genetic information in a single-stranded molecule of RNA, instead of the more common double-stranded DNA. When it infects a cell, the virus deploys a special enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, that enables it to copy itself and then paste its own genes into the new cell’s DNA. It then becomes part of that cell forever; when the cell divides, the virus goes with it. Scientists have long suspected that if a retrovirus happens to infect a human sperm cell or egg, which is rare, and if that embryo survives—which is rarer still—the retrovirus could take its place in the blueprint of our species, passed from mother to child, and from one generation to the next, much like a gene for eye color or asthma. On May 13, 1961, two articles appeared in Nature, authored by a total of nine people, including Sydney Brenner, François Jacob and Jim Watson, announcing the isolation of messenger RNA (mRNA)

On May 13, 1961, two articles appeared in Nature, authored by a total of nine people, including Sydney Brenner, François Jacob and Jim Watson, announcing the isolation of messenger RNA (mRNA)  In Theory of the Gimmick (Harvard University Press, 2020), Ngai tracks the gimmick through a number of guises: stage props, wigs, stainless-steel banana slicers, temp agencies, fraudulent photographs, subprime loans, technological doodads, the novel of ideas. Across its many forms, the gimmick arouses our suspicion. When we say something is a gimmick, we mean it is overrated and deceptive, that you would have to be a sucker to fall for it. Yet gimmicks exert a strange hold on us. As with a magic show, we can enjoy the gimmick even while we know we are being tricked.

In Theory of the Gimmick (Harvard University Press, 2020), Ngai tracks the gimmick through a number of guises: stage props, wigs, stainless-steel banana slicers, temp agencies, fraudulent photographs, subprime loans, technological doodads, the novel of ideas. Across its many forms, the gimmick arouses our suspicion. When we say something is a gimmick, we mean it is overrated and deceptive, that you would have to be a sucker to fall for it. Yet gimmicks exert a strange hold on us. As with a magic show, we can enjoy the gimmick even while we know we are being tricked. Rome’s

Rome’s  A core principle of the academic movement that shot through elite schools in America since the early nineties was the view that individual rights, humanism, and the democratic process are all just stalking-horses for white supremacy. The concept, as articulated in books like former corporate consultant Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility (Amazon’s

A core principle of the academic movement that shot through elite schools in America since the early nineties was the view that individual rights, humanism, and the democratic process are all just stalking-horses for white supremacy. The concept, as articulated in books like former corporate consultant Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility (Amazon’s  O

O William James in turn experienced a vastation of his own. In Varieties of Religious Experience he provides a report by a ‘French correspondent’ – in reality, himself – that describes how on an ordinary evening, at twilight, ‘suddenly there fell upon me without warning, just as if it came out of darkness, a horrible fear of my own existence’. His terror became embodied in the image of an epileptic patient he had seen in an asylum, ‘like a sculptured Egyptian cat or Peruvian mummy, moving nothing but his black eyes … That shape am I.’

William James in turn experienced a vastation of his own. In Varieties of Religious Experience he provides a report by a ‘French correspondent’ – in reality, himself – that describes how on an ordinary evening, at twilight, ‘suddenly there fell upon me without warning, just as if it came out of darkness, a horrible fear of my own existence’. His terror became embodied in the image of an epileptic patient he had seen in an asylum, ‘like a sculptured Egyptian cat or Peruvian mummy, moving nothing but his black eyes … That shape am I.’ The millimeter-long roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans has about 20,000 genes—and so do you. Of course, only the human in this comparison is capable of creating either a circulatory system or a sonnet, a state of affairs that made this genetic equivalence one of the most confusing insights to come out of the Human Genome Project. But there are ways of accounting for some of our complexity beyond the level of genes, and as one new study shows, they may matter far more than people have assumed.

The millimeter-long roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans has about 20,000 genes—and so do you. Of course, only the human in this comparison is capable of creating either a circulatory system or a sonnet, a state of affairs that made this genetic equivalence one of the most confusing insights to come out of the Human Genome Project. But there are ways of accounting for some of our complexity beyond the level of genes, and as one new study shows, they may matter far more than people have assumed. In October, 2010, an Italian religious historian named Alberto Melloni stood over a small cherrywood box in the reading room of the Laurentian Library, in Florence. The box was old and slightly scuffed, and inked in places with words in Latin. It had been stored for several centuries inside one of the library’s distinctive sloping reading desks, which were designed by Michelangelo. Melloni slid the lid off the box. Inside was a yellow silk scarf, and wrapped in the scarf was a thirteenth-century Bible, no larger than the palm of his hand, which was falling to pieces. The Bible was “a very poor one,” Melloni told me recently. “Very dark. Very nothing.” But it had a singular history. In 1685, a Jesuit priest who had travelled to China gave the Bible to the Medici family, suggesting that it had belonged to Marco Polo, the medieval explorer who reached the court of Kublai Khan around 1275. Although the story was unlikely, the book had almost certainly been carried by an early missionary to China and spent several centuries there, being handled by scholars and mandarins—making it a remarkable object in the history of Christianity in Asia.

In October, 2010, an Italian religious historian named Alberto Melloni stood over a small cherrywood box in the reading room of the Laurentian Library, in Florence. The box was old and slightly scuffed, and inked in places with words in Latin. It had been stored for several centuries inside one of the library’s distinctive sloping reading desks, which were designed by Michelangelo. Melloni slid the lid off the box. Inside was a yellow silk scarf, and wrapped in the scarf was a thirteenth-century Bible, no larger than the palm of his hand, which was falling to pieces. The Bible was “a very poor one,” Melloni told me recently. “Very dark. Very nothing.” But it had a singular history. In 1685, a Jesuit priest who had travelled to China gave the Bible to the Medici family, suggesting that it had belonged to Marco Polo, the medieval explorer who reached the court of Kublai Khan around 1275. Although the story was unlikely, the book had almost certainly been carried by an early missionary to China and spent several centuries there, being handled by scholars and mandarins—making it a remarkable object in the history of Christianity in Asia. “No one in the world feels the weakness of general characterizing more than I.” So lamented Johann Gottfried von Herder, towering figure of the German Enlightenment, in his 1774 treatise This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity. “One draws together peoples and periods of time that follow one another in an eternal succession like waves of the sea,” Herder wrote. “Whom has one painted? Whom has the depicting word captured?” For Herder, the Enlightenment dream of grasping human history as a seamless whole came up against the irreducible particularity of individuals and cultures.

“No one in the world feels the weakness of general characterizing more than I.” So lamented Johann Gottfried von Herder, towering figure of the German Enlightenment, in his 1774 treatise This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity. “One draws together peoples and periods of time that follow one another in an eternal succession like waves of the sea,” Herder wrote. “Whom has one painted? Whom has the depicting word captured?” For Herder, the Enlightenment dream of grasping human history as a seamless whole came up against the irreducible particularity of individuals and cultures. In September 1991, a pair of German hikers in the Ötztal Alps, near the border between Austria and Italy, spotted something brown and human-shaped sticking out of a glacier. They immediately reported this to the authorities, thinking they had discovered the body of someone who had died while hiking. While they were correct about it being a dead body, they were a little off on the timing: what they found turned out to be the mummified corpse of a man who had died sometime before 3100 BCE.

In September 1991, a pair of German hikers in the Ötztal Alps, near the border between Austria and Italy, spotted something brown and human-shaped sticking out of a glacier. They immediately reported this to the authorities, thinking they had discovered the body of someone who had died while hiking. While they were correct about it being a dead body, they were a little off on the timing: what they found turned out to be the mummified corpse of a man who had died sometime before 3100 BCE. Since it emerged

Since it emerged