Category: Archives

Introducing Pierre Klossowski’s ‘The Suspended Vocation’

Brian Evenson at Music & Literature:

This is not to say that Klossowski was standoffish. One of the interesting things about him is that once you finally notice him you begin to see his shadowy presence everywhere in twentieth-century French culture. He was, for instance, an early French translator of Walter Benjamin—as well as Wittgenstein, Heidegger, and Kafka, among others. When very young, he was a secretary for André Gide and appears semidisguised as a character in Gide’s novel The Counterfeiters, a novel he appears to have helped edit and for which he also made illustrations (which were turned down for being too overtly erotic). The older brother of the painter Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, better known as Balthus, Klossowski was an artist himself, and his work is at once naïve and pornographically explicit in a way that sometimes references occult texts, mythology, and Klossowski’s own prose. He was a friend of Georges Bataille—and indeed Bataille’s own investigation of erotism might best be read in counterpoint to Klossowski. He was involved marginally with surrealists, spent time in a Dominican seminary, was later involved with the existentialists, and wrote philosophical texts on Friedrich Nietzsche and the Marquis de Sade that were influential for post-structuralism. His book-length economico-philosophical essay La Monnaie vivante (Living Currency) Foucault called “the best book of our times.” Fiction writer, philosopher, translator, and visual artist, Klossowski worked in many modes and media and seemed to touch the lives of many of the literary and artistic figures we now admire. Indeed, once he’s noticed, it’s hard not to suspect he’s lurking even where you don’t see him.

This is not to say that Klossowski was standoffish. One of the interesting things about him is that once you finally notice him you begin to see his shadowy presence everywhere in twentieth-century French culture. He was, for instance, an early French translator of Walter Benjamin—as well as Wittgenstein, Heidegger, and Kafka, among others. When very young, he was a secretary for André Gide and appears semidisguised as a character in Gide’s novel The Counterfeiters, a novel he appears to have helped edit and for which he also made illustrations (which were turned down for being too overtly erotic). The older brother of the painter Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, better known as Balthus, Klossowski was an artist himself, and his work is at once naïve and pornographically explicit in a way that sometimes references occult texts, mythology, and Klossowski’s own prose. He was a friend of Georges Bataille—and indeed Bataille’s own investigation of erotism might best be read in counterpoint to Klossowski. He was involved marginally with surrealists, spent time in a Dominican seminary, was later involved with the existentialists, and wrote philosophical texts on Friedrich Nietzsche and the Marquis de Sade that were influential for post-structuralism. His book-length economico-philosophical essay La Monnaie vivante (Living Currency) Foucault called “the best book of our times.” Fiction writer, philosopher, translator, and visual artist, Klossowski worked in many modes and media and seemed to touch the lives of many of the literary and artistic figures we now admire. Indeed, once he’s noticed, it’s hard not to suspect he’s lurking even where you don’t see him.

more here.

Cortex Envy and IQ

Mark Dery at Cabinet:

For much of their history, intelligence tests have been rotten with the cultural and class biases of their makers, a diagnostic deck stacked against minorities, immigrants, and those at the bottom of the wage pyramid. Test designers have equated English-language fluency with intelligence, presumed a familiarity with upper-class pastimes such as tennis, and expected the examinee to provide the word “shrewd” as a synonym for “Jewish.” As late as the 1960 revision, the Stanford-Binet was presenting six-year-old children with crude cartoons of two women, one obviously Anglo-Saxon, the other a golliwog caricature of an African-American, with a broad nose and thick lips. The test accepted only one correct answer to the question, “Which is prettier?”12

For much of their history, intelligence tests have been rotten with the cultural and class biases of their makers, a diagnostic deck stacked against minorities, immigrants, and those at the bottom of the wage pyramid. Test designers have equated English-language fluency with intelligence, presumed a familiarity with upper-class pastimes such as tennis, and expected the examinee to provide the word “shrewd” as a synonym for “Jewish.” As late as the 1960 revision, the Stanford-Binet was presenting six-year-old children with crude cartoons of two women, one obviously Anglo-Saxon, the other a golliwog caricature of an African-American, with a broad nose and thick lips. The test accepted only one correct answer to the question, “Which is prettier?”12

Terman begrudgingly conceded that environmental factors might play some small part in IQ-test scores. For the most part, though, he was a thoroughgoing hereditarian.

more here.

The Allies of Whiteness

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

A FEW LONG WEEKS AGO, during the Covid-19 pandemic but before the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department, I wrote about racism in publishing, looking particularly at whom publishing lauds and applauds. The Pulitzer Prizes, those cherished gewgaws of the would-be kings and queens of publishing, had just been handed out a few days earlier. As my column noted, the award for feature writing was handed to a young white male journalist named Ben Taub. A darling at The New Yorker (who has, per one journalist who served with him on a panel, “an unlimited budget”), Taub won his Pulitzer for an article titled “Guantánamo’s Darkest Secret.”

A FEW LONG WEEKS AGO, during the Covid-19 pandemic but before the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department, I wrote about racism in publishing, looking particularly at whom publishing lauds and applauds. The Pulitzer Prizes, those cherished gewgaws of the would-be kings and queens of publishing, had just been handed out a few days earlier. As my column noted, the award for feature writing was handed to a young white male journalist named Ben Taub. A darling at The New Yorker (who has, per one journalist who served with him on a panel, “an unlimited budget”), Taub won his Pulitzer for an article titled “Guantánamo’s Darkest Secret.”

None of this was surprising; staff writers at The New Yorker (whose editor David Remnick sits on the Pulitzer Prize Board) win Pulitzers all the time and almost ritualistically; the only question seems to be who among them will be selected. Except that there was a problem. Much of Taub’s story was drawn from a book by Mohamedou Ould Salahi about his time in the Guantánamo prison, not from any length of field reporting (he spent only a week with Salahi). Salahi’s book, Guantánamo Diary, did not receive a Pulitzer Prize. A white man won a prestigious award for telling a story that a brown man had already told. The white people involved noticed nothing amiss. Nor did any of them—either those at The New Yorker or anyone associated with the board of the Pulitzer Prizes—ever bother to respond to questions I had raised.

I bring this up now because in the weeks since, as America’s simmering pot of racial cruelties has boiled over, many who are instrumental in lubricating the rise of the Ben Taubs of the world, or scores of others like him, have cast themselves as “white allies.” Never mind their routine preference for promoting those in whom they “see themselves”; never mind their secret biases, their always-white darlings. Those who once simply hid behind a haute snobbery (think Vogue editor Anna Wintour) are now, thanks to the fear of cultural irrelevance, donning the garb of white allyship.

It is a tricky situation. At a time when so many feel their public face requires some sort of pretense to being “white allies,” it becomes necessary to distinguish them. White allies, the long-standing and authentic ones, are not simply performing allyship on social media; they have been—since before yesterday—finding ways to make changes; they are reaching out in real life, considering and critiquing their own choices and their own complicity. (Margaret Sullivan’s column this week in the Washington Post is a good example of this.) On the other hand, these interloping others—I call them “allies of whiteness”—are interested only in the most superficial, most easy-to-use, convenient-from-country-homes sorts of allyship.

More here.

Elephants Have a Secret Weapon Against Cancer

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

In 2012, on a whim, Vincent Lynch decided to search the genome of the African elephant to see if it had extra anti-cancer genes. Cancers happen when cells build up mutations in their DNA that allow them to grow and divide uncontrollably. Bigger animals, whose bodies comprise more cells, should therefore have a higher risk of cancer. This is true within species: On average, taller humans are more likely to develop tumors than shorter ones, and bigger dogs have a higher cancer risk than smaller ones.

In 2012, on a whim, Vincent Lynch decided to search the genome of the African elephant to see if it had extra anti-cancer genes. Cancers happen when cells build up mutations in their DNA that allow them to grow and divide uncontrollably. Bigger animals, whose bodies comprise more cells, should therefore have a higher risk of cancer. This is true within species: On average, taller humans are more likely to develop tumors than shorter ones, and bigger dogs have a higher cancer risk than smaller ones.

But this trend breaks down when you look across species. Elephants are no more susceptible to tumors than Chihuahuas, and whales are no more likely to develop cancers than humans—if anything, their risk is lower. That’s especially strange because big animals also tend to have longer life spans, giving more opportunities for each of their already abundant cells to become cancerous. They ought to be walking (or swimming) masses of tumors—but clearly they aren’t. For the vast majority of mammals that have been studied, the odds of dying from cancer range from 1 to 10 percent, whether you’re talking about a 50-gram grass mouse or a 5,000-kilogram African elephant.

This puzzling trend is called Peto’s paradox, named after the British epidemiologist Richard Peto, who described it in the 1970s. Since then, biologists have proposed hundreds of hypotheses to explain it. Some note that larger animals have lower metabolic rates; this reduces the rate at which they acquire mutations. Others have suggested that in big animals, tumors need more time to reach a lethal size; during that time, the tumors likely to grow debilitating secondary tumors of their own.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Acquainted With the Night

I have been one acquainted with the night.

I have walked out in rain—and back in rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light.

I have looked down the saddest city lane.

I have passed by the watchman on his beat

And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain.

I have stood still and stopped the sound of feet

When far away an interrupted cry

Came over houses from another street,

But not to call me back or say good-by;

And further still at an unearthly height,

One luminary clock against the sky

Proclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right.

I have been one acquainted with the night.

by Robert Frost

Wednesday, June 24, 2020

Our addiction to predictions will be the end of us

Samanth Subramanian in Politico:

Trawling through the news archives, I found predictions of “the new normal” — the post-pandemic world — from as early as the first week of March. At the time, the United Kingdom hadn’t yet gone into lockdown; neither had France, India or Spain. In the United States, President Donald Trump had just about stopped declaring that the virus would miraculously disappear.

Roughly 3,400 people had died as of March 6 but you could still fly from London to New York. The contours of the months to come were fuzzy and indistinct, and yet there we were, making forecasts about life after the coronavirus.

The situation today is, in relative terms, not hugely different. Several governments don’t yet know when and how they will move out of lockdown. We don’t know who will be left immune after this spell of sickness, or if there will be a vaccine, or if there will be a second wave of COVID-19 this winter, or if the virus will mutate, or when it’ll be possible to travel freely across the world once again.

But even in the midst of this flux and uncertainty, we are toiling away at more predictions.

More here.

‘Recovered’ from COVID-19 doesn’t mean healthy again

Mike Moffitt in the San Francisco Chronicle:

Most people who catch the new coronavirus don’t experience severe symptoms, and some have no symptoms at all. COVID-19 saves its worst for relatively few.

Most people who catch the new coronavirus don’t experience severe symptoms, and some have no symptoms at all. COVID-19 saves its worst for relatively few.

ICU nurse Sherie Antoinette has seen the serious cases first hand.

The lucky ones — if you can call them that — recover, but not in the sense that their lives are back to normal. For some, the damage is permanent. Their organs will never fully heal.

“When they say ’recovered,’ they don’t tell you that that means you may need a lung transplant,” Antoinette wrote in a Twitter post. “Or that you may come back after discharge with a massive heart attack or stroke, because COVID makes your blood thick as hell. Or that you may have to be on oxygen for the rest of your life.”

More here.

Cognitive Ease and the Illusion of Truth

Noam Chomsky on BLM, the Bernie Sanders campaign, Trump, and other things

Michael Brooks at Reader Supported News:

MB: What are your thoughts as you look at the movement that has erupted after the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police?

NC: The first thing that comes to mind is the absolutely unprecedented scope and scale of participation, engagement, and public support. If you look at polls, it’s astonishing. The public support both for Black Lives Matter and the protests is well beyond what it was, say, for Martin Luther King at the peak of his popularity, at the time of the “I Have a Dream” speech. It’s also far beyond the level of public reaction to earlier police killings.

NC: The first thing that comes to mind is the absolutely unprecedented scope and scale of participation, engagement, and public support. If you look at polls, it’s astonishing. The public support both for Black Lives Matter and the protests is well beyond what it was, say, for Martin Luther King at the peak of his popularity, at the time of the “I Have a Dream” speech. It’s also far beyond the level of public reaction to earlier police killings.

It may be the most similar to the reaction to the beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles. They beat him almost to death. Most of the attackers were freed in the courts without charge. There was a week of protest; sixty people were killed, and they had to call in federal troops to quell the protests. But that was in Los Angeles. Now it’s everywhere.

And it’s not just the police killing — it’s background issues. It’s beginning to move into concern, inquiries, and protests about the facts that lead to events like this occurring. This rise in consciousness is aided by the rise in consciousness of four hundred years of vicious repression.

More here.

The Exploitative Cancer Drug Industry Needs to Be Euthanized

Ian Neff in Jacobin:

The cost of cancer treatment in the United States continues to skyrocket. It’s gotten so bad that GoFundMe has special tips to help people with cancer beg for their lives from strangers on the internet. You can scroll through all the cancer-related fundraisers and see endless stories of people who need tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars for treatment. The comments are filled with people in similar situations, heartbreakingly earnest prayers, and some who are envious that their own campaigns didn’t go so well. In a recent paper, I argued that the for-profit pharmaceutical industry will always stand as a threat to justice in cancer care. The solution to that threat is not timid regulation, but to replace that industry entirely. The social burden of cancer makes it a particularly ripe field for supplanting for-profit drug development with a socialized model, and the existing industry and research structure can be transformed to serve the public rather than profits.

The cost of cancer treatment in the United States continues to skyrocket. It’s gotten so bad that GoFundMe has special tips to help people with cancer beg for their lives from strangers on the internet. You can scroll through all the cancer-related fundraisers and see endless stories of people who need tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars for treatment. The comments are filled with people in similar situations, heartbreakingly earnest prayers, and some who are envious that their own campaigns didn’t go so well. In a recent paper, I argued that the for-profit pharmaceutical industry will always stand as a threat to justice in cancer care. The solution to that threat is not timid regulation, but to replace that industry entirely. The social burden of cancer makes it a particularly ripe field for supplanting for-profit drug development with a socialized model, and the existing industry and research structure can be transformed to serve the public rather than profits.

Why start with cancer research? Cancer is, in the language of anthropology, a “total social fact.” It permeates society, simultaneously uniting and dividing everything with its tendrils, creating borders between Susan Sontag’s “kingdom of the sick” and the dominion of the well. It threatens life, it strains relationships, and it makes insufferable demands of patients and their families alike. As S. Lochlann Jain explains, cancer is “at one moment a paper trail and at another an identity . . . a statistic . . . a bankruptcy . . . a scientific quandary.” Cancer is a cultural weight, physical threat, and potential economic ruin in one package you can carry without so much as a tote bag.

These costs have real health consequences for people with cancer. A quarter of people who have trouble paying for their treatment cut their pills in half or otherwise ration medicine to get by. A recent study shows that almost half of patients who have to pay more than $2,000 out of pocket for pills to treat cancer have to abandon that treatment altogether. This shouldn’t surprise anyone since 40 percent of Americans can’t scrape together $400 in a pinch. At the same time, intravenous drug prices have risen 18 percent faster than inflation. There’s no escape from the crushing burden of drug costs.

More here.

The Coronavirus and Right-Wing Postmodernism

John Horgan in Scientific American:

I’m recovering from flu, so I’ve spent more time than usual by myself lately, with odd ideas swirling around in my feverish brain. Recently a bunch of different thoughts–about Thomas Kuhn, AIDS denialism, George Bush, Errol Morris, Trump and of course the coronavirus—clumped together in a way that made me think: blog post! I’ll start with Kuhn. He is the philosopher of science who argued, in his 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, that science can never achieve absolute, objective truth. Reality is unknowable, forever hidden behind the veil of our assumptions, preconceptions and definitions, or “paradigms.” At least that’s what I thought Kuhn argued, but his writings were so murky that I couldn’t be sure. When I interviewed him in 1991, I was determined to discover just how skeptical he really was.

I’m recovering from flu, so I’ve spent more time than usual by myself lately, with odd ideas swirling around in my feverish brain. Recently a bunch of different thoughts–about Thomas Kuhn, AIDS denialism, George Bush, Errol Morris, Trump and of course the coronavirus—clumped together in a way that made me think: blog post! I’ll start with Kuhn. He is the philosopher of science who argued, in his 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, that science can never achieve absolute, objective truth. Reality is unknowable, forever hidden behind the veil of our assumptions, preconceptions and definitions, or “paradigms.” At least that’s what I thought Kuhn argued, but his writings were so murky that I couldn’t be sure. When I interviewed him in 1991, I was determined to discover just how skeptical he really was.

Really, really skeptical, it turned out. We spoke for several hours in Kuhn’s office at MIT, and I found myself sticking up for the idea that science gets some things right. At one point, I told Kuhn that his philosophy applied to fields with a “metaphysical” cast, like quantum mechanics, but not to more straightforward realms, like the study of infectious diseases. As an example, I brought up AIDS. A few skeptics, notably virologist Peter Duesberg, were questioning whether the so-called human immunodeficiency virus, HIV, actually causes AIDS. These skeptics were either right or wrong, I said, not just right or wrong within the context of a particular social-cultural-linguistic context. Kuhn shook his head vigorously and said:

I would say there are too many grounds for slippage. There’s a whole spectrum of viruses involved. There’s a whole spectrum of conditions of which AIDS is one or several or so forth… I think when this all comes out you’ll say, Boy, I see why [Duesberg] believed that, and he was onto something. I’m not going to tell you he was right, or he was wrong. We don’t believe any of that anymore. But neither do we believe anymore what these guys who said it was the cause believe… The question as to what AIDS is as a clinical condition and what the disease entity is itself is not — it is subject to adjustment. And so forth. When one learns to think differently about these things, if one does, the question of right and wrong will no longer seem to be the relevant question.

Wednesday Poem

Dad Poem (Ultrasound #2)

—with a line from Gwendolyn Brooks

Months into the plague now,

I am disallowed

entry even into the waiting

room with Mom, escorted outside

instead by men armed

with guns & bottles

of hand sanitizer, their entire

countenance its own American

metaphor. So the first time

I see you in full force,

I am pacing maniacally

up & down the block outside,

Facetiming the radiologist

& your mother too,

her arm angled like a cellist’s

to help me see.

We are dazzled by the sight

of each bone in your feet,

the pulsing black archipelago

of your heart, your fists in front

of your face like mine when I

was only just born, ten times as big

as you are now. Your great-grandmother

calls me Tyson the moment she sees

this pose. Prefigures a boy

built for conflict, her barbarous

and metal little man. She leaves

the world only months after we learn

you are entering into it. And her mind

the year before that. In the dementia’s final

days, she envisions herself as a girl

of seventeen, running through fields

of strawberries, unfettered as a king

-fisher. I watch your stance and imagine

her laughter echoing back across the ages,

you, her youngest descendant born into

freedom, our littlest burden-lifter, world

-beater, avant-garde percussionist

swinging darkness into song.

by Joshua Bennett

from Poets.org

Bollywood Grooves

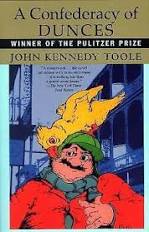

John Kennedy Toole @50

James McWilliams at Public Books:

The New York publishers were wrong. A Confederacy of Dunces did, in fact, make a point, a fundamental one. Percy grasped it immediately: the book was a screed against American materialism and optimism, a defense of the oddball outcasts who live on the fringes and resist the push of progress, and a celebration of those who try to drop out with dignity.

The New York publishers were wrong. A Confederacy of Dunces did, in fact, make a point, a fundamental one. Percy grasped it immediately: the book was a screed against American materialism and optimism, a defense of the oddball outcasts who live on the fringes and resist the push of progress, and a celebration of those who try to drop out with dignity.

The novel delivered one of American literature’s finest condemnations of a national obsession so pervasive that, with the exception of the South, the United States experienced it the way a fish experiences water: A Confederacy of Dunces challenged the whole idea of work. Toole’s critique begins and ends with the novel’s protagonist, the unprecedented antihero Ignatius J. Reilly. Ignatius, 30, is a flatulent and grandiose medievalist who lives with his mother, reads Boethius, and, between chronic bouts of masturbation and moviegoing, scribbles “a lengthy indictment against our century.”

more here.

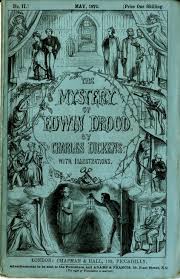

The Mystery of Edwin Drood

Frances Wilson at Literary Review:

While he was writing Edwin Drood, Dickens was imbibing large quantities of opium, a drug that allows us, Thomas De Quincey explained in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, access to a ‘second life’. Opium also allows the ‘guilty man’, De Quincey continued, to regain ‘for one night … the hopes of his youth, and hands washed pure of blood’. But at the same time as releasing the guilty man from his chains, taking opium causes further feelings of guilt. ‘In the one crime of OPIUM’, wailed Coleridge, whose life was destroyed by it, ‘what crime have I not made myself guilty of!’

While he was writing Edwin Drood, Dickens was imbibing large quantities of opium, a drug that allows us, Thomas De Quincey explained in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, access to a ‘second life’. Opium also allows the ‘guilty man’, De Quincey continued, to regain ‘for one night … the hopes of his youth, and hands washed pure of blood’. But at the same time as releasing the guilty man from his chains, taking opium causes further feelings of guilt. ‘In the one crime of OPIUM’, wailed Coleridge, whose life was destroyed by it, ‘what crime have I not made myself guilty of!’

Dickens was the master of guilt: Little Dorrit’s Arthur Clenham is a study in the psychopathology of the guilty man, and so is John Jasper. But it was his own guilt that increasingly haunted Dickens, and the figure of Jasper was a disguised self-portrait.

more here.

Tuesday, June 23, 2020

Frans de Waal On Animal Intelligence And Emotions

Mark Leviton in The Sun:

Leviton: Darwin wrote that the difference in mind between humans and higher animals is “one of degree and not of kind.” What do you think he meant?

Leviton: Darwin wrote that the difference in mind between humans and higher animals is “one of degree and not of kind.” What do you think he meant?

De Waal: I think Darwin meant that the way we think is not fundamentally different from the way other species think, and I’m completely in agreement with him, even though people have attacked him for it over the years and said this was one of the things he was wrong about. There are some elements to human thought processes that are special, but the whole structure of cognition — how it works, what we can comprehend, how we find solutions to problems — is not so different. Human cognition is a variety of animal cognition.

Leviton: Why do you think some people have such a hard time accepting that idea?

De Waal: It’s strange, especially at a time when neuroscience is showing us the similarities between the monkey brain and the human brain. For instance, there’s no part of a human brain that you don’t also find in a monkey brain. There are no synapses or transmitters that are different. Even the blood supply is the same. We do have bigger brains, it’s true, which is certainly important.

Let me tell you a funny story about that.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Maria Konnikova on Poker, Psychology, and Reason

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

The best chess and Go players in the world aren’t human beings any more; they’re artificially-intelligent computer programs. But the best poker players are still humans. Poker is a laboratory for understanding how rationality works in real-world situations: it features stochastic events, incomplete information, Bayesian updating, game theory, reading other people, a battle between emotions and reason, and real-world stakes. Maria Konnikova started in psychology, turned to writing, and then took up professional-level poker, and has learned a lot along the way about the challenges of being rational. We talk about what games like poker can teach us about thinking and human psychology.

The best chess and Go players in the world aren’t human beings any more; they’re artificially-intelligent computer programs. But the best poker players are still humans. Poker is a laboratory for understanding how rationality works in real-world situations: it features stochastic events, incomplete information, Bayesian updating, game theory, reading other people, a battle between emotions and reason, and real-world stakes. Maria Konnikova started in psychology, turned to writing, and then took up professional-level poker, and has learned a lot along the way about the challenges of being rational. We talk about what games like poker can teach us about thinking and human psychology.

More here.

The New Truth

Jacob Siegel in Tablet:

There are distinct and deep-rooted traditions of rational empiricism and religious sermonizing in American history. But these two modes seem to have become fused together in a new form of argumentation that is validated by elite institutions like the universities, The New York Times, Gracie Mansion, and especially on the new technology platforms where battles over the discourse are now waged. The new mode is argument by commandment: It borrows the form to game the discourse of rational argumentation in order to issue moral commandments. No official doctrine yet exists for this syncretic belief system but its features have been on display in all of the major debates over political morality of the past decade. Marrying the technical nomenclature of rational proof to the soaring eschatology of the sermon, it releases adherents from the normal bounds of reason. The arguer-commander is animated by a vision of secular hell—unremitting racial oppression that never improves despite myths about progress; society as a ceaseless subjection to rape and sexual assault; Trump himself, arriving to inaugurate a Luciferean reign of torture. Those in possession of this vision do not offer the possibility of redemption or transcendence, they come to deliver justice. In possession of justice, the arguer-commander is free at any moment to throw off the cloak of reason and proclaim you a bigot—racist, sexist, transphobe—who must be fired from your job and socially shunned.

There are distinct and deep-rooted traditions of rational empiricism and religious sermonizing in American history. But these two modes seem to have become fused together in a new form of argumentation that is validated by elite institutions like the universities, The New York Times, Gracie Mansion, and especially on the new technology platforms where battles over the discourse are now waged. The new mode is argument by commandment: It borrows the form to game the discourse of rational argumentation in order to issue moral commandments. No official doctrine yet exists for this syncretic belief system but its features have been on display in all of the major debates over political morality of the past decade. Marrying the technical nomenclature of rational proof to the soaring eschatology of the sermon, it releases adherents from the normal bounds of reason. The arguer-commander is animated by a vision of secular hell—unremitting racial oppression that never improves despite myths about progress; society as a ceaseless subjection to rape and sexual assault; Trump himself, arriving to inaugurate a Luciferean reign of torture. Those in possession of this vision do not offer the possibility of redemption or transcendence, they come to deliver justice. In possession of justice, the arguer-commander is free at any moment to throw off the cloak of reason and proclaim you a bigot—racist, sexist, transphobe—who must be fired from your job and socially shunned.

More here.