Susan B. Glasser in The New Yorker:

Precisely at noon on Wednesday, Donald Trump’s disastrous Presidency will end, two weeks to the day after he unleashed a mob of his supporters to storm the Capitol, seeking to overturn the election results, and one week to the day after he was impeached for so doing. He leaves behind a city and a country reeling from four hundred thousand Americans dead, as of Tuesday, from a pandemic whose gravity he downplayed and denied; an economic crisis; and an internal political rift so great that it invites comparisons to the Civil War.

Precisely at noon on Wednesday, Donald Trump’s disastrous Presidency will end, two weeks to the day after he unleashed a mob of his supporters to storm the Capitol, seeking to overturn the election results, and one week to the day after he was impeached for so doing. He leaves behind a city and a country reeling from four hundred thousand Americans dead, as of Tuesday, from a pandemic whose gravity he downplayed and denied; an economic crisis; and an internal political rift so great that it invites comparisons to the Civil War.

In the end, Trump was everything his haters feared—a chaos candidate, in the prescient words of one of his 2016 rivals, who became a chaos President. An American demagogue, he embraced division and racial discord, railed against a “deep state” within his own government, praised autocrats and attacked allies, politicized the administration of justice, monetized the Presidency for himself and his children, and presided over a tumultuous, turnover-ridden Administration via impulsive tweets. He leaves office, Gallup reported this week, with the lowest average approval ratings in the history of the modern Presidency. Defeated by Joe Biden in the 2020 election by seven million votes, Trump became the first incumbent seeking reëlection to see his party lose the White House, Senate, and the House of Representatives since Herbert Hoover, in 1932. A liar on an unprecedented scale, Trump made more than thirty thousand false statements in the course of his Presidency, according to the Washington Post, culminating in perhaps the biggest lie of all: that he won an election that he decisively lost.

Anne Schult: Over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, reflections on contagious disease as allegory have abounded, and some of the most canonical texts engaging with this trope—from Susan Sontag’s

Anne Schult: Over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, reflections on contagious disease as allegory have abounded, and some of the most canonical texts engaging with this trope—from Susan Sontag’s  What is the world made of? How does it behave? These questions, aimed at the most basic level of reality, are the subject of fundamental physics. What counts as fundamental is somewhat contestable, but it includes our best understanding of matter and energy, space and time, and dynamical laws, as well as complex emergent structures and the sweep of the cosmos. Few people are better positioned to talk about fundamental physics than Frank Wilczek, a Nobel Laureate who has made significant contributions to our understanding of the strong interactions, dark matter, black holes, and condensed matter, as well as proposing the existence of

What is the world made of? How does it behave? These questions, aimed at the most basic level of reality, are the subject of fundamental physics. What counts as fundamental is somewhat contestable, but it includes our best understanding of matter and energy, space and time, and dynamical laws, as well as complex emergent structures and the sweep of the cosmos. Few people are better positioned to talk about fundamental physics than Frank Wilczek, a Nobel Laureate who has made significant contributions to our understanding of the strong interactions, dark matter, black holes, and condensed matter, as well as proposing the existence of  It is time to define responsibility and hold these companies accountable for how they aid and abet criminal activity. And it is time to listen to those who have shouted from the rooftops about these issues for years, as opposed to allowing Silicon Valley leaders to dictate the terms.

It is time to define responsibility and hold these companies accountable for how they aid and abet criminal activity. And it is time to listen to those who have shouted from the rooftops about these issues for years, as opposed to allowing Silicon Valley leaders to dictate the terms. Earlier in his career, Gregory writes, theater was a “drug to relieve the pain of living.” But escaping into his “calling” came with no shortage of throbbing side effects. One of the “most awful” days of Gregory’s life is the one when he directs a scene at Strasberg’s Actors Studio only to receive a brutal critique from the famed teacher in front of his fellow students, among them Marilyn Monroe and Paul Newman. (He’d stay away from Strasberg’s class for months.) The belated success of his Alice came only after a succession of early failures: being fired from three consecutive directorships at small regional theaters. An “enfant terrible” in these years, Gregory hired a chemist to synthesize the smell of “rotting flesh” for a production in Philadelphia, resulting in an actor vomiting during a tech rehearsal and Gregory’s dismissal from the play. Another firing, from a theater in Los Angeles, came after he was punched by the program’s benefactor, the movie star Gregory Peck.

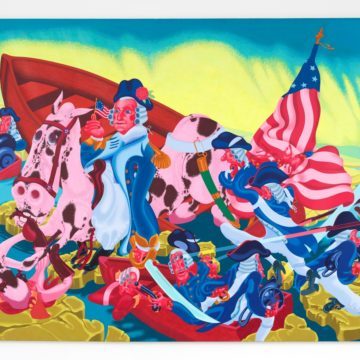

Earlier in his career, Gregory writes, theater was a “drug to relieve the pain of living.” But escaping into his “calling” came with no shortage of throbbing side effects. One of the “most awful” days of Gregory’s life is the one when he directs a scene at Strasberg’s Actors Studio only to receive a brutal critique from the famed teacher in front of his fellow students, among them Marilyn Monroe and Paul Newman. (He’d stay away from Strasberg’s class for months.) The belated success of his Alice came only after a succession of early failures: being fired from three consecutive directorships at small regional theaters. An “enfant terrible” in these years, Gregory hired a chemist to synthesize the smell of “rotting flesh” for a production in Philadelphia, resulting in an actor vomiting during a tech rehearsal and Gregory’s dismissal from the play. Another firing, from a theater in Los Angeles, came after he was punched by the program’s benefactor, the movie star Gregory Peck. A mild sensation in the late Sixties, a cult artist in the early Aughts, and now a seasoned art world veteran, Saul, who is 86, is having a moment. “How long until Peter Saul is rediscovered once and for all,” Beau Rutland wrote on the occasion of Saul’s comprehensive 2017 show at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt. European retrospectives and newly respectful reviews have culminated in a two-floor survey at the New Museum last February. It is Saul’s first retrospective in New York City, accompanied by a lavish catalog and the publication of his “professional artist correspondence,” a fascinating collection of letters written to his parents and his longtime gallerist Allan Frumkin.

A mild sensation in the late Sixties, a cult artist in the early Aughts, and now a seasoned art world veteran, Saul, who is 86, is having a moment. “How long until Peter Saul is rediscovered once and for all,” Beau Rutland wrote on the occasion of Saul’s comprehensive 2017 show at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt. European retrospectives and newly respectful reviews have culminated in a two-floor survey at the New Museum last February. It is Saul’s first retrospective in New York City, accompanied by a lavish catalog and the publication of his “professional artist correspondence,” a fascinating collection of letters written to his parents and his longtime gallerist Allan Frumkin. It was 10 years ago that

It was 10 years ago that  After 35 years of sharing everything from a love for jazz music to tubes of lip gloss, twins Kimberly and Kelly Standard assumed that when they became sick with Covid-19 their experiences would be as identical as their DNA. The virus had different plans. Early last spring, the sisters from Rochester, Michigan, checked themselves into the hospital with fevers and shortness of breath. While Kelly was discharged after less than a week, her sister ended up in intensive care. Kimberly spent almost a month in critical condition, breathing through tubes and dipping in and out of shock. Weeks after Kelly had returned to their shared home, Kimberly was still relearning how to speak, walk and chew and swallow solid food she could barely taste. Nearly a year later, the sisters are bedeviled by the bizarrely divergent paths their illnesses took.

After 35 years of sharing everything from a love for jazz music to tubes of lip gloss, twins Kimberly and Kelly Standard assumed that when they became sick with Covid-19 their experiences would be as identical as their DNA. The virus had different plans. Early last spring, the sisters from Rochester, Michigan, checked themselves into the hospital with fevers and shortness of breath. While Kelly was discharged after less than a week, her sister ended up in intensive care. Kimberly spent almost a month in critical condition, breathing through tubes and dipping in and out of shock. Weeks after Kelly had returned to their shared home, Kimberly was still relearning how to speak, walk and chew and swallow solid food she could barely taste. Nearly a year later, the sisters are bedeviled by the bizarrely divergent paths their illnesses took. Over the past 10 years, numerous studies have shown that our obsession with happiness and high personal confidence may be making us less content with our lives, and less effective at reaching our actual goals. Indeed, we may often be happier when we stop focusing on happiness altogether.

Over the past 10 years, numerous studies have shown that our obsession with happiness and high personal confidence may be making us less content with our lives, and less effective at reaching our actual goals. Indeed, we may often be happier when we stop focusing on happiness altogether. Spider legs seem to have minds of their own. According to findings published

Spider legs seem to have minds of their own. According to findings published  Critics of Silicon Valley censorship for years heard the same refrain: tech platforms like Facebook, Google and Twitter are private corporations and can host or ban whoever they want. If you don’t like what they are doing, the solution is not to complain or to regulate them. Instead, go create your own social media platform that operates the way you think it should.

Critics of Silicon Valley censorship for years heard the same refrain: tech platforms like Facebook, Google and Twitter are private corporations and can host or ban whoever they want. If you don’t like what they are doing, the solution is not to complain or to regulate them. Instead, go create your own social media platform that operates the way you think it should.

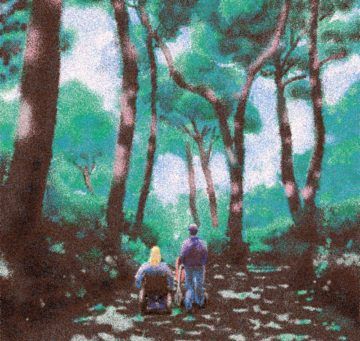

It was a night in mid-April that I fell asleep to the phrase this is too hard pinging through my brain, and they were the first words to cross my mind when I opened my eyes the next morning. I texted my sisters: “Remember the easy days when it was JUST a baby and cancer???” I pulled myself out of bed, plopped heavily into my wheelchair and stared in the mirror with my fingers splayed across my growing belly. That day we had to decide if my partner Micah would start a second round of chemotherapy treatments that would weaken his ability to fight against this new virus if he caught it, or forgo the treatment and change his odds against cancer. Our baby would arrive in a few weeks.

It was a night in mid-April that I fell asleep to the phrase this is too hard pinging through my brain, and they were the first words to cross my mind when I opened my eyes the next morning. I texted my sisters: “Remember the easy days when it was JUST a baby and cancer???” I pulled myself out of bed, plopped heavily into my wheelchair and stared in the mirror with my fingers splayed across my growing belly. That day we had to decide if my partner Micah would start a second round of chemotherapy treatments that would weaken his ability to fight against this new virus if he caught it, or forgo the treatment and change his odds against cancer. Our baby would arrive in a few weeks. After Donald Trump lost the US presidency last year, he retained the consolation prize of his Twitter account. Commentators debated how Mr Trump would seek to profit from the 88 million followers he had accumulated: a new TV career or another presidential bid? Yet on 8 January, he lost his cherished platform after he was permanently suspended by Twitter because of “the risk of further incitement of violence”. Two days earlier a rabble of Trump fanatics, conspiracy theorists and white supremacists had stormed the US Capitol, resulting in five deaths. In a video posted on Twitter, Mr Trump told the mob, “We love you” and later tweeted: “These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide victory is so viciously & unceremoniously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long.”

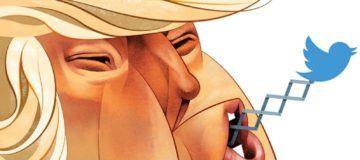

After Donald Trump lost the US presidency last year, he retained the consolation prize of his Twitter account. Commentators debated how Mr Trump would seek to profit from the 88 million followers he had accumulated: a new TV career or another presidential bid? Yet on 8 January, he lost his cherished platform after he was permanently suspended by Twitter because of “the risk of further incitement of violence”. Two days earlier a rabble of Trump fanatics, conspiracy theorists and white supremacists had stormed the US Capitol, resulting in five deaths. In a video posted on Twitter, Mr Trump told the mob, “We love you” and later tweeted: “These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide victory is so viciously & unceremoniously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long.”