Bob Blaisdell in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

What are you working on right now?

I just published a novel in Norway two months ago. I’m now writing another novel which somehow is related, and I’ve started it, I’ve written a hundred pages or so, so I’m in the middle of the beginning of that, which is the hardest part. But that’s what I’m doing.

I just published a novel in Norway two months ago. I’m now writing another novel which somehow is related, and I’ve started it, I’ve written a hundred pages or so, so I’m in the middle of the beginning of that, which is the hardest part. But that’s what I’m doing.

The middle of the beginning is the hardest part? Not the beginning but the middle of the beginning is the hardest?

Yeah, yeah. That’s the hardest part. Before the novel decides itself and you just can follow it along. Before that happens, you have to make the space where it later will unfold, and the space, it seems when you are writing, is nothing in itself. The feeling is that nothing is leaving the page, it is flat and dull and all you want to do is to start again afresh. Once I did that, started again and again, and in the end I had 800 pages of beginnings. So now I tend to stick with it, no matter how bad it feels, trying to be patient, hoping for something to evolve. That’s hard work and you don’t know whether it’s going to be something or not, and it’s not good in itself. It’s just like building a scaffolding or something.

More here.

In 1972,

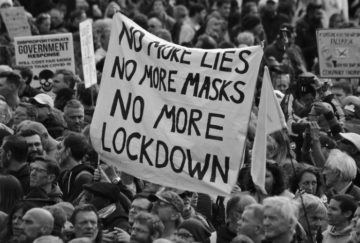

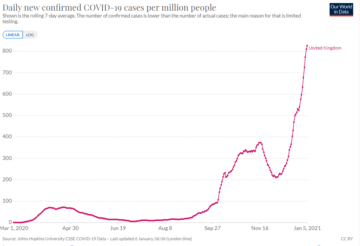

In 1972,  Over the past year, mobilizations around the world have sprung up against governmental efforts to contain the coronavirus through lockdowns, social distancing guidelines, mask mandates, and vaccines. Led in many cases by angry freelancers and the self-employed, amplified by entrepreneurs of speculative and totalizing prophecies, these movements are less what José Ortega y Gasset called “the revolt of the masses” and more “the revolt of the Mittelstand”—small- and medium-sized businesses. In comparison to the populism that dominated discussion in 2017, they are less tethered to mediagenic leaders and parties, slipperier on the traditional political spectrum, and less fixated on the assumption of state power. The spectacular and deadly storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6 has understandably eclipsed all other mobilizations for the moment. Yet, by drawing back the lens, we can see where aspects of a narrowly defined Trumpism overlap with a broader global phenomenon—and where they do not.

Over the past year, mobilizations around the world have sprung up against governmental efforts to contain the coronavirus through lockdowns, social distancing guidelines, mask mandates, and vaccines. Led in many cases by angry freelancers and the self-employed, amplified by entrepreneurs of speculative and totalizing prophecies, these movements are less what José Ortega y Gasset called “the revolt of the masses” and more “the revolt of the Mittelstand”—small- and medium-sized businesses. In comparison to the populism that dominated discussion in 2017, they are less tethered to mediagenic leaders and parties, slipperier on the traditional political spectrum, and less fixated on the assumption of state power. The spectacular and deadly storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6 has understandably eclipsed all other mobilizations for the moment. Yet, by drawing back the lens, we can see where aspects of a narrowly defined Trumpism overlap with a broader global phenomenon—and where they do not. But let’s say it again: to call Gray a misanthrope or a reactionary or a nationalist (or to apply to him any other term from the vocabulary of contemporary political morality) is to miss the point. His books are not attacks on humanity as such. Nor is he tubthumping for a particular politics or even a particular morality (I’ll come in a moment to the question of whether or not a specific politics can or should be extracted from Gray’s work). Instead, his books are in the first instance the record of an honourable attempt to discover what can be said about human beings if we dispense, as thoroughly as we can, with the things that human beings have said about themselves. To step out of Gray’s Total Perspective Vortex and ask, “But what’s left?” is to misunderstand the purpose of the Vortex. What’s left, when Gray is finished, is everything: life, death, nature, the universe. All there is, in other words. The point is the seeing. In the final sentence of Straw Dogs, he asks, “Can we not think of the aim of life as being simply to see?”

But let’s say it again: to call Gray a misanthrope or a reactionary or a nationalist (or to apply to him any other term from the vocabulary of contemporary political morality) is to miss the point. His books are not attacks on humanity as such. Nor is he tubthumping for a particular politics or even a particular morality (I’ll come in a moment to the question of whether or not a specific politics can or should be extracted from Gray’s work). Instead, his books are in the first instance the record of an honourable attempt to discover what can be said about human beings if we dispense, as thoroughly as we can, with the things that human beings have said about themselves. To step out of Gray’s Total Perspective Vortex and ask, “But what’s left?” is to misunderstand the purpose of the Vortex. What’s left, when Gray is finished, is everything: life, death, nature, the universe. All there is, in other words. The point is the seeing. In the final sentence of Straw Dogs, he asks, “Can we not think of the aim of life as being simply to see?” The brief examination of the work of Heinrich von Kleist (1777-1811) conducted here is intended as an essay in criticism in the spirit of Sartre: “Une technique romanesque renvoie toujours à la métaphysique du romancier. La tâche du critique est de dégager celle-ci avant d’apprécier celle-là.” The concept of metaphysics Sartre employs refers, on my reading, to the hardly controversial thought that literary works generally (not only novels) render worlds imaginatively present, and that these worlds exhibit principles of intelligibility. To free up the metaphysics of an artistic world, then, is to solicit the deep criteria (or categories) that organize that world. Such criticism brings the form of an aesthetically achieved world to light and demonstrates how that form is made salient linguistically, rhetorically, narratively, dramatically, and so forth. Call this the non-formalistic criticism of form. Needless to say, the account of Kleist’s work I develop here does not aspire to exhaustiveness. The aim, rather, is to limn the contours of Kleist’s artistic achievement such that acknowledgement of its originality and importance is felt to constitute an intellectual obligation. Acknowledgement, a variant of Hegelian “recognition,” deserves to replace the now faded and, in Sartre’s use, merely technical notion of appreciation.

The brief examination of the work of Heinrich von Kleist (1777-1811) conducted here is intended as an essay in criticism in the spirit of Sartre: “Une technique romanesque renvoie toujours à la métaphysique du romancier. La tâche du critique est de dégager celle-ci avant d’apprécier celle-là.” The concept of metaphysics Sartre employs refers, on my reading, to the hardly controversial thought that literary works generally (not only novels) render worlds imaginatively present, and that these worlds exhibit principles of intelligibility. To free up the metaphysics of an artistic world, then, is to solicit the deep criteria (or categories) that organize that world. Such criticism brings the form of an aesthetically achieved world to light and demonstrates how that form is made salient linguistically, rhetorically, narratively, dramatically, and so forth. Call this the non-formalistic criticism of form. Needless to say, the account of Kleist’s work I develop here does not aspire to exhaustiveness. The aim, rather, is to limn the contours of Kleist’s artistic achievement such that acknowledgement of its originality and importance is felt to constitute an intellectual obligation. Acknowledgement, a variant of Hegelian “recognition,” deserves to replace the now faded and, in Sartre’s use, merely technical notion of appreciation. Visualize, if you will, a group of bacteria cells. They are kind of silly looking, when you get right down to it: shaped like a sphere or a pill, sometimes covered in tiny hairs or spikes. While technically alive, it is hard to imagine them as being particularly intelligent, much less capable of storing information like artificially intelligent machines such as computers. Curiously, that’s exactly what a group of researchers just did: edited DNA inside individual bacteria cells in order to store digital data.

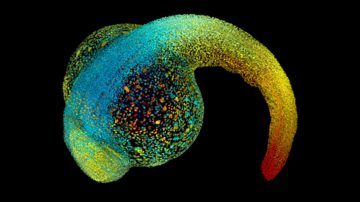

Visualize, if you will, a group of bacteria cells. They are kind of silly looking, when you get right down to it: shaped like a sphere or a pill, sometimes covered in tiny hairs or spikes. While technically alive, it is hard to imagine them as being particularly intelligent, much less capable of storing information like artificially intelligent machines such as computers. Curiously, that’s exactly what a group of researchers just did: edited DNA inside individual bacteria cells in order to store digital data. At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain. None of this could happen without forces that squeeze, bend and tug the growing animal into shape. Even when it reaches adulthood, its cells will continue to respond to pushing and pulling — by each other and from the environment. Yet the manner in which bodies and tissues take form remains “one of the most important, and still poorly understood, questions of our time”, says developmental biologist Amy Shyer, who studies morphogenesis at the Rockefeller University in New York City. For decades, biologists have focused on the ways in which genes and other biomolecules shape bodies, mainly because the tools to analyse these signals are readily available and always improving. Mechanical forces have received much less attention.

At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain. None of this could happen without forces that squeeze, bend and tug the growing animal into shape. Even when it reaches adulthood, its cells will continue to respond to pushing and pulling — by each other and from the environment. Yet the manner in which bodies and tissues take form remains “one of the most important, and still poorly understood, questions of our time”, says developmental biologist Amy Shyer, who studies morphogenesis at the Rockefeller University in New York City. For decades, biologists have focused on the ways in which genes and other biomolecules shape bodies, mainly because the tools to analyse these signals are readily available and always improving. Mechanical forces have received much less attention. Mr. Faruqi has been credited among scholars with the revival of Urdu literature, especially from the 18th and 19th centuries. His output as a scholar, editor, publisher, critic, literary historian, translator and acclaimed writer of both poetry and novels was varied and prolific.

Mr. Faruqi has been credited among scholars with the revival of Urdu literature, especially from the 18th and 19th centuries. His output as a scholar, editor, publisher, critic, literary historian, translator and acclaimed writer of both poetry and novels was varied and prolific. Let’s start with the good news.

Let’s start with the good news.

THE BELIEVER: Your books combine elements of memoir, epistemological analysis, ontological meditation, anthropological observation, and plenty of other genres. They are usually written in the first person (singular or plural), and sometimes in the second person. How did you decide to adopt this freedom of style, and what do you hope to accomplish with it?

THE BELIEVER: Your books combine elements of memoir, epistemological analysis, ontological meditation, anthropological observation, and plenty of other genres. They are usually written in the first person (singular or plural), and sometimes in the second person. How did you decide to adopt this freedom of style, and what do you hope to accomplish with it? She was a poet who could carve both stillness and speed from the gap and one who, for me, lit the match. She was the poet who first taught me to obsess over the responsibility of the line break and in her house, she held her shoulders like a woman no longer afraid to let it be known she liked to be amused. Whatever she and her line breaks had been through, she’d long ago found the courage to say.

She was a poet who could carve both stillness and speed from the gap and one who, for me, lit the match. She was the poet who first taught me to obsess over the responsibility of the line break and in her house, she held her shoulders like a woman no longer afraid to let it be known she liked to be amused. Whatever she and her line breaks had been through, she’d long ago found the courage to say. The violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol Building last week, incited by President Donald Trump, serves as the grimmest moment in one of the darkest chapters in the nation’s history. Yet the rioters’ actions—and Trump’s own role in, and response to, them—come as little surprise to many, particularly those who have been studying the president’s mental fitness and the psychology of his most ardent followers since he took office. One such person is Bandy X. Lee, a forensic psychiatrist and president of the World Mental Health Coalition.

The violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol Building last week, incited by President Donald Trump, serves as the grimmest moment in one of the darkest chapters in the nation’s history. Yet the rioters’ actions—and Trump’s own role in, and response to, them—come as little surprise to many, particularly those who have been studying the president’s mental fitness and the psychology of his most ardent followers since he took office. One such person is Bandy X. Lee, a forensic psychiatrist and president of the World Mental Health Coalition. The spectacular violence in the Capitol on January 6th was the outcome of

The spectacular violence in the Capitol on January 6th was the outcome of