Alicia Ault in Smithsonian:

As long as vaccines have existed, humans have been suspicious of both the shots and those who administer them. The first inoculation deployed in America, against smallpox in the 1720s, was decried as antithetical to God’s will. An outraged citizen tossed a bomb through the window of a house where pro-vaccination Boston minister Cotton Mather lived to dissuade him from his mission. It did not stop Mather’s campaign.

As long as vaccines have existed, humans have been suspicious of both the shots and those who administer them. The first inoculation deployed in America, against smallpox in the 1720s, was decried as antithetical to God’s will. An outraged citizen tossed a bomb through the window of a house where pro-vaccination Boston minister Cotton Mather lived to dissuade him from his mission. It did not stop Mather’s campaign.

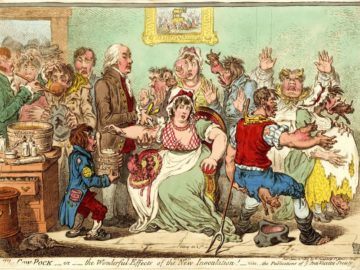

After British physician Edward Jenner developed a more effective smallpox vaccine in the late 1700s—using a related cowpox virus as the inoculant—fear of the unknown continued despite its success in preventing transmission. An 1802 cartoon, entitled The Cow Pock—or—the Wonderful Effects of the New Innoculation, depicts a startled crowd of vaccinees who have seemingly morphed into a cow-human chimera, with the front ends of cattle leaping out of their mouths, eyes, ears and behinds. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, says the outlandish fiction of the cartoon continues to reverberate with false claims that vaccines cause autism, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, or that the messenger RNA-based Covid-19 vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna lead to infertility. “People are just frightened whenever you inject them with a biological, so their imaginations run wild,” Offit recently told attendees of “Racing for Vaccines,” a webinar organized by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. “The birth of the first anti-vaccine movement was with the first vaccine,” says Offit. People don’t want to be compelled to take a vaccine, so “they create these images, many of which obviously are based on false notions.”

More here.

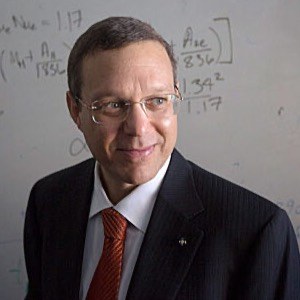

For 7 years as president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Robert Tjian helped steer hundreds of millions of dollars to scientists probing provocative ideas that might transform biology and biomedicine. So the biochemist was intrigued a couple of years ago when his graduate student David McSwiggen uncovered data likely to fuel excitement about a process called phase separation, already one of the hottest concepts in cell biology.

For 7 years as president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Robert Tjian helped steer hundreds of millions of dollars to scientists probing provocative ideas that might transform biology and biomedicine. So the biochemist was intrigued a couple of years ago when his graduate student David McSwiggen uncovered data likely to fuel excitement about a process called phase separation, already one of the hottest concepts in cell biology. To observers of the American class system in the 21st century, the common conflation of social class with income is a source of amusement as well as frustration. Depending on how you slice and dice the population, you can come up with as many income classes as you like—four classes with 25%, or the 99% against the 1%, or the 99.99% against the 0.01%. In the United States, as in most advanced societies, class tends to be a compound of income, wealth, education, ethnicity, religion, and race, in various proportions. There has never been a society in which the ruling class consisted merely of a basket of random rich people.

To observers of the American class system in the 21st century, the common conflation of social class with income is a source of amusement as well as frustration. Depending on how you slice and dice the population, you can come up with as many income classes as you like—four classes with 25%, or the 99% against the 1%, or the 99.99% against the 0.01%. In the United States, as in most advanced societies, class tends to be a compound of income, wealth, education, ethnicity, religion, and race, in various proportions. There has never been a society in which the ruling class consisted merely of a basket of random rich people. Imagine bits of wood trapped in eddies of a stream, going round and round atop the waters that flow beneath them. The image comes to mind in response to a surprising show—surprisingly great, contrary to my skeptical expectation—at

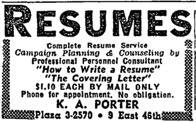

Imagine bits of wood trapped in eddies of a stream, going round and round atop the waters that flow beneath them. The image comes to mind in response to a surprising show—surprisingly great, contrary to my skeptical expectation—at  For as long as we have been writing cover letters, or covering letters, and whatever preceded covering letters, writers have sought the support of those who have mastered the craft du jour. Lurie describes what he believes is the earliest example of an advertisement for how-to guides on writing “cover letters.” He says, “The first true sign that cover letters were mainstream enough to cause job applicants some anxiety was an advertisement in 1965, in the Boston Globe.” Again, it should come as no surprise, that one will find an advertisement for a how-to guide on “the covering letter” (again in the New York Times) in August 1955—more than a decade before the example that Mr. Lurie cites in the Boston Globe, and indeed much closer to the pair of Dutch Boy ads.

For as long as we have been writing cover letters, or covering letters, and whatever preceded covering letters, writers have sought the support of those who have mastered the craft du jour. Lurie describes what he believes is the earliest example of an advertisement for how-to guides on writing “cover letters.” He says, “The first true sign that cover letters were mainstream enough to cause job applicants some anxiety was an advertisement in 1965, in the Boston Globe.” Again, it should come as no surprise, that one will find an advertisement for a how-to guide on “the covering letter” (again in the New York Times) in August 1955—more than a decade before the example that Mr. Lurie cites in the Boston Globe, and indeed much closer to the pair of Dutch Boy ads. One relevant fact is that people over 65 have a higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than younger people do, and those over 75 are at even higher risk.

One relevant fact is that people over 65 have a higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than younger people do, and those over 75 are at even higher risk. The possible existence of technologically advanced extraterrestrial civilizations — not just alien microbes, but cultures as advanced (or much more) than our own — is one of the most provocative questions in modern science. So provocative that it’s difficult to talk about the idea in a rational, dispassionate way; there are those who loudly insist that the probability of advanced alien cultures existing is essentially one, even without direct evidence, and others are so exhausted by overblown claims in popular media that they want to squelch any such talk. Astronomer Avi Loeb thinks we should be taking this possibility seriously, so much so that he suggested that the recent interstellar interloper

The possible existence of technologically advanced extraterrestrial civilizations — not just alien microbes, but cultures as advanced (or much more) than our own — is one of the most provocative questions in modern science. So provocative that it’s difficult to talk about the idea in a rational, dispassionate way; there are those who loudly insist that the probability of advanced alien cultures existing is essentially one, even without direct evidence, and others are so exhausted by overblown claims in popular media that they want to squelch any such talk. Astronomer Avi Loeb thinks we should be taking this possibility seriously, so much so that he suggested that the recent interstellar interloper  Our differences over policy are substantial, but they’re

Our differences over policy are substantial, but they’re  I

I  JERUSALEM — Israel, which leads the world in vaccinating its population against the coronavirus, has produced some encouraging news: Early results show a significant drop in infection after just one shot of a two-dose vaccine, and better than expected results after both doses. Public health experts caution that the data, based on the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, is preliminary and has not been subjected to clinical trials. Even so, Dr. Anat Ekka Zohar, vice president of Maccabi Health Services, one of the Israeli health maintenance organizations that released the data, called it “very encouraging.” In the first early report, Clalit, Israel’s largest health fund, compared 200,000 people aged 60 or over who received a first dose of the vaccine to a matched group of 200,000 who had not been vaccinated yet. It said that 14 to 18 days after their shots, the partially vaccinated patients were

JERUSALEM — Israel, which leads the world in vaccinating its population against the coronavirus, has produced some encouraging news: Early results show a significant drop in infection after just one shot of a two-dose vaccine, and better than expected results after both doses. Public health experts caution that the data, based on the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, is preliminary and has not been subjected to clinical trials. Even so, Dr. Anat Ekka Zohar, vice president of Maccabi Health Services, one of the Israeli health maintenance organizations that released the data, called it “very encouraging.” In the first early report, Clalit, Israel’s largest health fund, compared 200,000 people aged 60 or over who received a first dose of the vaccine to a matched group of 200,000 who had not been vaccinated yet. It said that 14 to 18 days after their shots, the partially vaccinated patients were  Didion, now eighty-six, has been an object of fascination ever since, boosted by the black-lace renaissance she experienced after publishing “The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005), her raw and ruminative account of the months following Dunne’s sudden death. Generally, writers who hold readers’ imaginations across decades do so because there’s something unsolved in their project, something that doesn’t square and thus seems subject to the realm of magic. In Didion’s case, a disconnect appears between the jobber-like shape of her writing life—a shape she often emphasizes in descriptions of her working habits—and the forms that emerged as the work accrued. For all her success, Didion was seventy before she finished a nonfiction book that was not drawn from newsstand-magazine assignments. She and Dunne started doing that work with an eye to covering the bills, and then a little more. (Their Post rates allowed them to rent a tumbledown Hollywood mansion, buy a banana-colored Corvette Stingray, raise a child, and dine well.) And yet the mosaic-like nonfiction books that Didion produced are the opposite of jobber books, or market-pitched books, or even useful, fibrous, admirably executed books. These are strange books, unusually shaped. They changed the way that journalistic storytelling and analysis were done.

Didion, now eighty-six, has been an object of fascination ever since, boosted by the black-lace renaissance she experienced after publishing “The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005), her raw and ruminative account of the months following Dunne’s sudden death. Generally, writers who hold readers’ imaginations across decades do so because there’s something unsolved in their project, something that doesn’t square and thus seems subject to the realm of magic. In Didion’s case, a disconnect appears between the jobber-like shape of her writing life—a shape she often emphasizes in descriptions of her working habits—and the forms that emerged as the work accrued. For all her success, Didion was seventy before she finished a nonfiction book that was not drawn from newsstand-magazine assignments. She and Dunne started doing that work with an eye to covering the bills, and then a little more. (Their Post rates allowed them to rent a tumbledown Hollywood mansion, buy a banana-colored Corvette Stingray, raise a child, and dine well.) And yet the mosaic-like nonfiction books that Didion produced are the opposite of jobber books, or market-pitched books, or even useful, fibrous, admirably executed books. These are strange books, unusually shaped. They changed the way that journalistic storytelling and analysis were done. SM

SM  In April 2020, during the

In April 2020, during the  Kenny Chow was born in Myanmar, and moved to New York City in 1987. He worked for years as a diamond setter for a jeweller, earning enough to buy a house for his family before he was laid off in 2011. At that point, Chow decided to become a taxi driver like his brother, scraping together financing to buy a taxi medallion for $750,000. This allowed him to operate as a sole proprietor, with the medallion as an asset.

Kenny Chow was born in Myanmar, and moved to New York City in 1987. He worked for years as a diamond setter for a jeweller, earning enough to buy a house for his family before he was laid off in 2011. At that point, Chow decided to become a taxi driver like his brother, scraping together financing to buy a taxi medallion for $750,000. This allowed him to operate as a sole proprietor, with the medallion as an asset.