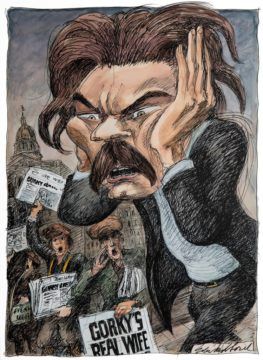

Edward Sorel at the New York Times:

In April 1906, Czar Nicholas caved in to protests from around the world, and released Maxim Gorky from the prison into which he had thrown him. Mark Twain and other writers, hearing that the celebrated author of “The Lower Depths” had been freed, invited him to New York City, and Gorky, still harassed by the secret police, accepted. With him on the voyage was the actress Maria Andreyeva.

In April 1906, Czar Nicholas caved in to protests from around the world, and released Maxim Gorky from the prison into which he had thrown him. Mark Twain and other writers, hearing that the celebrated author of “The Lower Depths” had been freed, invited him to New York City, and Gorky, still harassed by the secret police, accepted. With him on the voyage was the actress Maria Andreyeva.

Docking in Hoboken, Gorky was cheered by thousands of Russian immigrants, and a day later he was the guest of honor at a white-tie dinner arranged by Twain. Gorky, who spoke no English, came with an interpreter. Through him, he implored the guests to donate money to aid his Bolshevik comrades in overthrowing the czar.

more here.

Elizabeth Kolbert’s favourite movie is the end-of-the-world comedy

Elizabeth Kolbert’s favourite movie is the end-of-the-world comedy  I’d read “Lolita” in college, and I was too lazy to bother to read it again when preparing for my part in “The Bookshop.” I was already a huge fan of Nabokov’s — I had bought copies of his memoir, “Speak, Memory,” in bulk to hand out to my friends at college, and I had worn thin his “Lectures on Russian Literature,” which are as withering as they are brilliant. (I’ll never forget my shocked delight at his excoriation of Dostoyevsky as “a mediocre writer with wastelands of literary platitudes.”)

I’d read “Lolita” in college, and I was too lazy to bother to read it again when preparing for my part in “The Bookshop.” I was already a huge fan of Nabokov’s — I had bought copies of his memoir, “Speak, Memory,” in bulk to hand out to my friends at college, and I had worn thin his “Lectures on Russian Literature,” which are as withering as they are brilliant. (I’ll never forget my shocked delight at his excoriation of Dostoyevsky as “a mediocre writer with wastelands of literary platitudes.”) Does history have a goal? Is it possible that all the human societies that existed are ultimately a prelude to establishing a system where one entity will govern everything the world over? The Oxford University philosopher

Does history have a goal? Is it possible that all the human societies that existed are ultimately a prelude to establishing a system where one entity will govern everything the world over? The Oxford University philosopher  Why did prescription opioids bring so much misery to the small towns of postindustrial America?

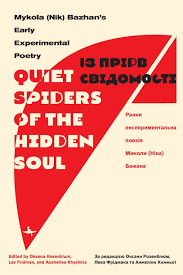

Why did prescription opioids bring so much misery to the small towns of postindustrial America? Despite his stature as a giant of Soviet Ukrainian literature, Bazhan remains all but unknown outside Ukraine. His work is formally sophisticated, his language rich, his subject matter multilayered. Translating him is, thus, no mean feat. But on top of that, for much of the 20th century, Bazhan’s pre-Party existence, and thus much of his best work, was unknown or inaccessible to potential translators. It is fitting, then, that the editors of this new volume of Bazhan’s work, Oksana Rosenblum, Lev Fridman, and Anzhelika Khyzhnia, have turned to the poet’s earlier poetry. The volume takes us through selections from Bazhan’s first three books, published in the giddy experimental atmosphere of the 1920s, before tackling some longer and more formally, thematically, and politically complex works from the early 1930s. Indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects of this book is the way it reveals the tension between Bazhan’s mercurial, untrammeled poetic genius and the creeping ideological strictures of Stalinism.

Despite his stature as a giant of Soviet Ukrainian literature, Bazhan remains all but unknown outside Ukraine. His work is formally sophisticated, his language rich, his subject matter multilayered. Translating him is, thus, no mean feat. But on top of that, for much of the 20th century, Bazhan’s pre-Party existence, and thus much of his best work, was unknown or inaccessible to potential translators. It is fitting, then, that the editors of this new volume of Bazhan’s work, Oksana Rosenblum, Lev Fridman, and Anzhelika Khyzhnia, have turned to the poet’s earlier poetry. The volume takes us through selections from Bazhan’s first three books, published in the giddy experimental atmosphere of the 1920s, before tackling some longer and more formally, thematically, and politically complex works from the early 1930s. Indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects of this book is the way it reveals the tension between Bazhan’s mercurial, untrammeled poetic genius and the creeping ideological strictures of Stalinism. It’s a little-known fact that Camus worked briefly as a meteorologist. For almost a year, from 1937-38, he wore a lab coat at the Algiers Geophysics Institute and catalogued measurements of atmospheric pressure from hundreds of weather stations across North Africa. The data had been piling up, and despite the arrogance of their imperial ambitions, the men who ran the Institute couldn’t attract enough funding. They didn’t have the money to hire a scientist trained for this “exacting and, in effect, stupefying task.”

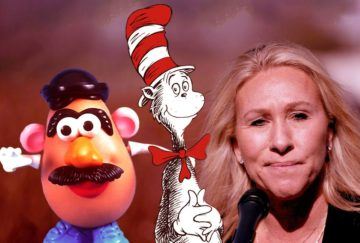

It’s a little-known fact that Camus worked briefly as a meteorologist. For almost a year, from 1937-38, he wore a lab coat at the Algiers Geophysics Institute and catalogued measurements of atmospheric pressure from hundreds of weather stations across North Africa. The data had been piling up, and despite the arrogance of their imperial ambitions, the men who ran the Institute couldn’t attract enough funding. They didn’t have the money to hire a scientist trained for this “exacting and, in effect, stupefying task.” It’s early, but Republicans have already seized on their strategy for winning the 2022 and 2024 elections. Of course, it does not depend on mundane tactics like “running on their record” or “making robust arguments about how their policies are better than their opponents.” The GOP is instead returning to the well that has, time and again, paid off handsomely: feigning umbrage over culture war flashpoints, usually ones wholly invented by the right or propped up with lies, to distract from substantive policy debates that actually impact American lives.

It’s early, but Republicans have already seized on their strategy for winning the 2022 and 2024 elections. Of course, it does not depend on mundane tactics like “running on their record” or “making robust arguments about how their policies are better than their opponents.” The GOP is instead returning to the well that has, time and again, paid off handsomely: feigning umbrage over culture war flashpoints, usually ones wholly invented by the right or propped up with lies, to distract from substantive policy debates that actually impact American lives. A new study asks the question: Do conversations end when people want them to? The short answer, it turns out, is no. The study, published this week in the journal the

A new study asks the question: Do conversations end when people want them to? The short answer, it turns out, is no. The study, published this week in the journal the  How can we summarise the Covid year from a broad historical perspective? Many people believe that the terrible toll coronavirus has taken demonstrates humanity’s helplessness in the face of nature’s might. In fact, 2020 has shown that humanity is far from helpless. Epidemics are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. Science has turned them into a manageable challenge.

How can we summarise the Covid year from a broad historical perspective? Many people believe that the terrible toll coronavirus has taken demonstrates humanity’s helplessness in the face of nature’s might. In fact, 2020 has shown that humanity is far from helpless. Epidemics are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. Science has turned them into a manageable challenge. The search for AI has always been about trying to build

The search for AI has always been about trying to build  No problem concerns journalists and press-watchers so much these days as the proliferation of conspiracy theories and misinformation on the internet. “We never confronted this level of conspiracy thinking in the U.S. previously,” Marty Baron, the former executive editor of The Washington Post, told Der Spiegel in a

No problem concerns journalists and press-watchers so much these days as the proliferation of conspiracy theories and misinformation on the internet. “We never confronted this level of conspiracy thinking in the U.S. previously,” Marty Baron, the former executive editor of The Washington Post, told Der Spiegel in a  Higgie’s book is a riposte to Renoir and centuries of unknowing and misjudging. Reading it is like travelling with an ever-excited companion who has lots to say, not all of it profound as it tumbles out in profusion and partisanship, and not always quite trustworthy, but always compelling. She is rightly enraged at the historical neglect of women artists. The marvellous illustrations here confirm her assessment of the quality of their work. Few nowadays would argue with her proposition that the history of art is ‘the history of many women not receiving their dues’. Beginning research for this book, she was ‘staggered’ by the depth and variety of paintings made by women, despite the formidable restrictions placed in their way, and despite believing herself already well informed on the subject. Ending her book, I felt much the same way, and excited at the prospect of finding out more.

Higgie’s book is a riposte to Renoir and centuries of unknowing and misjudging. Reading it is like travelling with an ever-excited companion who has lots to say, not all of it profound as it tumbles out in profusion and partisanship, and not always quite trustworthy, but always compelling. She is rightly enraged at the historical neglect of women artists. The marvellous illustrations here confirm her assessment of the quality of their work. Few nowadays would argue with her proposition that the history of art is ‘the history of many women not receiving their dues’. Beginning research for this book, she was ‘staggered’ by the depth and variety of paintings made by women, despite the formidable restrictions placed in their way, and despite believing herself already well informed on the subject. Ending her book, I felt much the same way, and excited at the prospect of finding out more.