In Maastricht, Nearing Departure

In two days, you will leave.

For now: dusk, wine, small cigar.

You will have stayed three months

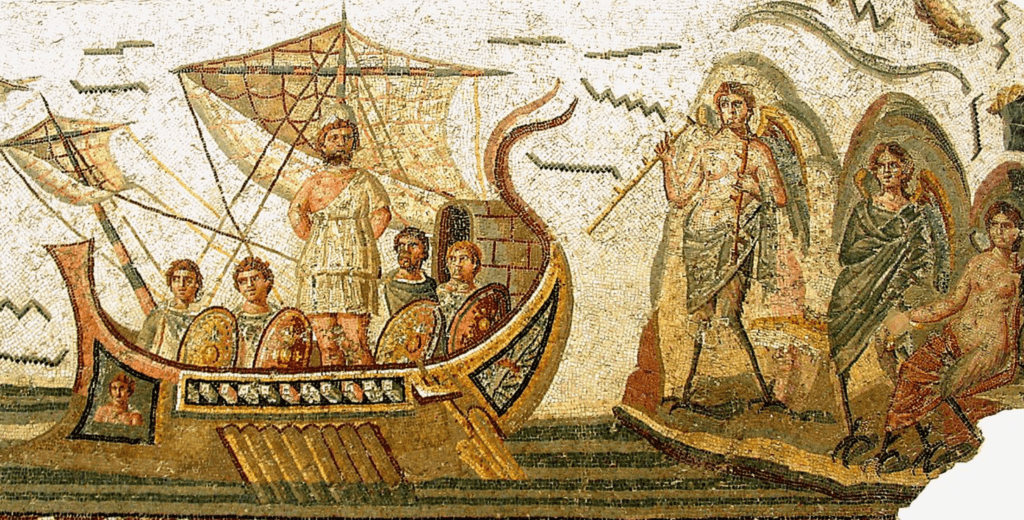

in Maastricht, a city occasioned

a couple thousand years ago

by soldiers crossing a river.

Walking over theirs

your footprints are invisible.

And something about mortality

sinks in slantwise.

It’s not that nothing you do matters

– although, frankly, how?

On these cobblestone streets

slicked by rain, there’s no traction.

Perhaps it’s the way

others can look through one, here,

small reminders of inconsequentiality.

But you could learn to love this.

The solitary bat juking in jagged circles.

The web of airplanes crisscrossing the sky,

their vapor trails pink-hued

by the already disappeared sun

as they near the edge of sight.

In all this, what’s not to love?

And night comes on so slowly,

the children asleep or nearing sleep,

the neighbors at card games on the balcony.

You could learn to love this.

The rich acrid taste lingering

as it leaves the mouth.

The cherishing and the letting go,

not always in that order.

by Tim DeJong

from the Ecotheo Review

The singer and guitarist Julien Baker makes raw, ghostly rock music that’s rooted in personal confession. But, unlike some artists operating in that mode, she’s figured out how to turn fragility into a display of fortitude. Baker’s songs—which explore themes of self-sabotage, atonement, and restitution—are aching but tough. This stems, in part, from Baker’s spiritual upbringing. She was raised in a devout Christian family near Memphis, Tennessee, and sang in church. When she came out as gay, at seventeen, she prepared herself for a swift denunciation, but her parents were compassionate. (Her father began scouring the Bible for passages about acceptance.) It’s possible to hear the echoes of Christian hymnals in her first two albums—ideas of love and grace, mentions of God and rejoicing. Baker has a tattoo that reads “God exists” and has said that she senses a kind of divine presence in art, or, as she once put it, evidence of “the possibility of man to be good.”

The singer and guitarist Julien Baker makes raw, ghostly rock music that’s rooted in personal confession. But, unlike some artists operating in that mode, she’s figured out how to turn fragility into a display of fortitude. Baker’s songs—which explore themes of self-sabotage, atonement, and restitution—are aching but tough. This stems, in part, from Baker’s spiritual upbringing. She was raised in a devout Christian family near Memphis, Tennessee, and sang in church. When she came out as gay, at seventeen, she prepared herself for a swift denunciation, but her parents were compassionate. (Her father began scouring the Bible for passages about acceptance.) It’s possible to hear the echoes of Christian hymnals in her first two albums—ideas of love and grace, mentions of God and rejoicing. Baker has a tattoo that reads “God exists” and has said that she senses a kind of divine presence in art, or, as she once put it, evidence of “the possibility of man to be good.” There is a story about René Descartes according to which the philosopher once owned a female automaton so convincing that a superstitious mariner, seeing the machine in operation, declared it the work of the devil and threw it into the sea. In some versions, Descartes is said to have built the automaton to replace his illegitimate daughter, Francine, who died in childhood. Though apocryphal, the tale persists because it combines a moving human tragedy with an intellectual problem – the relationship between mind and matter – that was central to Descartes’s own philosophy. It is a thought experiment disguised as a fairy tale, or perhaps vice versa.

There is a story about René Descartes according to which the philosopher once owned a female automaton so convincing that a superstitious mariner, seeing the machine in operation, declared it the work of the devil and threw it into the sea. In some versions, Descartes is said to have built the automaton to replace his illegitimate daughter, Francine, who died in childhood. Though apocryphal, the tale persists because it combines a moving human tragedy with an intellectual problem – the relationship between mind and matter – that was central to Descartes’s own philosophy. It is a thought experiment disguised as a fairy tale, or perhaps vice versa. I stumbled upon the legend of Nanda Devi and Nanda Kot and the lost CIA plutonium on a cold October night in 1987, sitting with friends, swilling cheap malt liquor around a roaring campfire in Yosemite. To my best recollection, Tucker recounted the most outrageous climbing yarn I’d ever heard. Tucker, whose low-slung build lent him an authoritative air, was one of those whose expression becomes more earnest and animated with each drink.

I stumbled upon the legend of Nanda Devi and Nanda Kot and the lost CIA plutonium on a cold October night in 1987, sitting with friends, swilling cheap malt liquor around a roaring campfire in Yosemite. To my best recollection, Tucker recounted the most outrageous climbing yarn I’d ever heard. Tucker, whose low-slung build lent him an authoritative air, was one of those whose expression becomes more earnest and animated with each drink. Historian Adam Tooze has argued that COVID-19 is the first economic crisis of the Anthropocene, a term encapsulating the idea that human impact on the environment and climate is so extreme that it has moved us out of the Holocene into a new geological epoch. While this argument remains the subject of deep disagreement among experts, those advocating for the Anthropocene emphasize that humans have so drastically altered the environment that we have become agents of transformations we cannot reliably control. Indeed, we are daily reminded of these effects by extreme weather events, species extinctions, and new global health emergencies.

Historian Adam Tooze has argued that COVID-19 is the first economic crisis of the Anthropocene, a term encapsulating the idea that human impact on the environment and climate is so extreme that it has moved us out of the Holocene into a new geological epoch. While this argument remains the subject of deep disagreement among experts, those advocating for the Anthropocene emphasize that humans have so drastically altered the environment that we have become agents of transformations we cannot reliably control. Indeed, we are daily reminded of these effects by extreme weather events, species extinctions, and new global health emergencies. Gonville and Caius College,

Gonville and Caius College,  In Russian, the word for oblivion is “zabveniye,” suggesting a prolonged or unending state of forgetting, a designated holding cell for all forgotten things. “Oblivion, the copycat of nonexistence, has a new twin brother: the dead memory of the collector,” Maria Stepanova writes in In Memory of Memory. Beautifully translated by the poet Sasha Dugdale, the book teems with oblivion. Family heirlooms are “dragged out of their oblivion,” experiences and memories are saved from its cold embrace. “All the past is carried off into oblivion,” Stepanova writes, “and it leaves a clear space for the future.” Oblivion is a kind of storage facility for exhausted histories. Inside its walls, Stepanova acts as collector and critic, and makes her temporary home.

In Russian, the word for oblivion is “zabveniye,” suggesting a prolonged or unending state of forgetting, a designated holding cell for all forgotten things. “Oblivion, the copycat of nonexistence, has a new twin brother: the dead memory of the collector,” Maria Stepanova writes in In Memory of Memory. Beautifully translated by the poet Sasha Dugdale, the book teems with oblivion. Family heirlooms are “dragged out of their oblivion,” experiences and memories are saved from its cold embrace. “All the past is carried off into oblivion,” Stepanova writes, “and it leaves a clear space for the future.” Oblivion is a kind of storage facility for exhausted histories. Inside its walls, Stepanova acts as collector and critic, and makes her temporary home. One of Adorno’s most sweeping and frequent characterizations of his project in Aesthetic Theory has it that the “task that confronts aesthetics today” is an “emancipation from absolute idealism.” The context (and the phrase itself) makes it explicit that he means Hegel, but only in so far as Hegel represents the culmination and essence of modern philosophy itself, or what Adorno calls “identity thinking.” He means by this that reflection on art should be freed from an aspiration for any even potential reconciliationist relation with contemporary society, or any sort of role in the potential rationalization or justification of any reform of any basic aspect of late modernity, or freed even from any aspiration for an aesthetic comprehension of that society, as if it had some coherent structure available for comprehension. He especially means that any expression or portrayal of the suffering caused in modern societies—capitalist, bourgeois society—that calls such a society to account in its own terms is excluded. Those terms have become irredeemably degraded and corrupt. Modern bourgeois society is in itself, root and branch, “wrong,” “false,” and the problem of art has become what it must be in such a world. What it must be is “negative,” and any attempt to understand Adorno must begin and end with that claim.

One of Adorno’s most sweeping and frequent characterizations of his project in Aesthetic Theory has it that the “task that confronts aesthetics today” is an “emancipation from absolute idealism.” The context (and the phrase itself) makes it explicit that he means Hegel, but only in so far as Hegel represents the culmination and essence of modern philosophy itself, or what Adorno calls “identity thinking.” He means by this that reflection on art should be freed from an aspiration for any even potential reconciliationist relation with contemporary society, or any sort of role in the potential rationalization or justification of any reform of any basic aspect of late modernity, or freed even from any aspiration for an aesthetic comprehension of that society, as if it had some coherent structure available for comprehension. He especially means that any expression or portrayal of the suffering caused in modern societies—capitalist, bourgeois society—that calls such a society to account in its own terms is excluded. Those terms have become irredeemably degraded and corrupt. Modern bourgeois society is in itself, root and branch, “wrong,” “false,” and the problem of art has become what it must be in such a world. What it must be is “negative,” and any attempt to understand Adorno must begin and end with that claim. The best cinematic performances don’t share some standard of craft or technique; what they have in common is a feeling of invention and discovery, of emotional depth and power, and a sense of self-consciousness regarding the idea and the art of performance itself. They also reflect broader transformations in the art of cinema during their times. Such actors as Joan Crawford, Barbara Stanwyck, and Jimmy Stewart were already stars in the high studio era of the nineteen-thirties, but their work became more freely expressive, more galvanic, in the postwar years, when the studios lost their tight grip on production—and when a new generation of directors made their mark in that freer environment. The French New Wave, developing new techniques with a new generation of actors (and crew), lifted layers of varnish from the art of acting to fill the screen with performances of jolting immediacy, spontaneity, and vulnerability.

The best cinematic performances don’t share some standard of craft or technique; what they have in common is a feeling of invention and discovery, of emotional depth and power, and a sense of self-consciousness regarding the idea and the art of performance itself. They also reflect broader transformations in the art of cinema during their times. Such actors as Joan Crawford, Barbara Stanwyck, and Jimmy Stewart were already stars in the high studio era of the nineteen-thirties, but their work became more freely expressive, more galvanic, in the postwar years, when the studios lost their tight grip on production—and when a new generation of directors made their mark in that freer environment. The French New Wave, developing new techniques with a new generation of actors (and crew), lifted layers of varnish from the art of acting to fill the screen with performances of jolting immediacy, spontaneity, and vulnerability. What we used to call genetic engineering has been subject to decades of bioethical scrutiny. Then, the arrival of CRISPR — which allows researchers to cut and paste gene sequences with vastly improved accuracy and efficiency — catapulted reassuringly distant science fiction into a pressing reality, and helped to concentrate minds. There’s now enough technical and popular writing on the technology and its ethics to fill many bookshelves. Given that not even ten years have passed since the first papers showing a practical use for CRISPR in human genome editing, these accounts inevitably go over much of the same territory. The differences are in the authors’ perspectives — broadly enthusiastic about the possibilities of genome editing, or not — and whether the focus is on the discoveries, the ramifications, the personalities involved or some combination. Two new books on the topic differ markedly in reach, style and emphasis. Reading them together gives insight into what the CRISPR story means — for knowledge, for society and for research as an endeavour.

What we used to call genetic engineering has been subject to decades of bioethical scrutiny. Then, the arrival of CRISPR — which allows researchers to cut and paste gene sequences with vastly improved accuracy and efficiency — catapulted reassuringly distant science fiction into a pressing reality, and helped to concentrate minds. There’s now enough technical and popular writing on the technology and its ethics to fill many bookshelves. Given that not even ten years have passed since the first papers showing a practical use for CRISPR in human genome editing, these accounts inevitably go over much of the same territory. The differences are in the authors’ perspectives — broadly enthusiastic about the possibilities of genome editing, or not — and whether the focus is on the discoveries, the ramifications, the personalities involved or some combination. Two new books on the topic differ markedly in reach, style and emphasis. Reading them together gives insight into what the CRISPR story means — for knowledge, for society and for research as an endeavour. I’ve never really understood why Georg Trakl talks about foreheads so much. I mean, you can imagine the word coming up once in a poem for some reason or other. I can even see that there is something fascinating about foreheads in that they are both of and not of the face. That’s to say, you don’t generally get a face without a forehead. The forehead sets up the face. And yet, it’s not really part of the face per se. The forehead is claimed to some degree by the rest of the head. It is a glimpse of the skull. It is a stoic and mostly featureless reminder that behind the bones of the head are the squishy parts of the brain. So, yes, I acknowledge that foreheads are, perhaps, more intriguing than at first they may seem.

I’ve never really understood why Georg Trakl talks about foreheads so much. I mean, you can imagine the word coming up once in a poem for some reason or other. I can even see that there is something fascinating about foreheads in that they are both of and not of the face. That’s to say, you don’t generally get a face without a forehead. The forehead sets up the face. And yet, it’s not really part of the face per se. The forehead is claimed to some degree by the rest of the head. It is a glimpse of the skull. It is a stoic and mostly featureless reminder that behind the bones of the head are the squishy parts of the brain. So, yes, I acknowledge that foreheads are, perhaps, more intriguing than at first they may seem. On a spectrum of philosophical topics, one might be tempted to put mathematics and morality on opposite ends. Math is one of the most pristine and rigorously-developed areas of human thought, while morality is notoriously contentious and resistant to consensus. But the more you dig into the depths, the more alike these two fields appear to be. Justin Clarke-Doane argues that they are very much alike indeed, especially when it comes to questions of “reality” and “objectivity” — but that they aren’t quite exactly analogous. We get a little bit into the weeds, but this is a case where close attention will pay off.

On a spectrum of philosophical topics, one might be tempted to put mathematics and morality on opposite ends. Math is one of the most pristine and rigorously-developed areas of human thought, while morality is notoriously contentious and resistant to consensus. But the more you dig into the depths, the more alike these two fields appear to be. Justin Clarke-Doane argues that they are very much alike indeed, especially when it comes to questions of “reality” and “objectivity” — but that they aren’t quite exactly analogous. We get a little bit into the weeds, but this is a case where close attention will pay off. A few weeks ago I served, as I sometimes do, on a dissertation-defense committee at a certain venerable Old World university. The event took place in a building whose foundations date to the thirteenth century, in a specialized “salle de soutenance” constructed in the nineteenth. The defendant was made to sit at a small desk beneath a looming podium, where we, the honorable members of the jury, were solemnly seated. The borrowed vocabulary from the world of the criminal trial is intentional and unmistakable. As usual I tried to play my part and look as grim and serious as possible. I confess I find it fairly easy, at least for a short time, to get swept up by the spirit of such rituals.

A few weeks ago I served, as I sometimes do, on a dissertation-defense committee at a certain venerable Old World university. The event took place in a building whose foundations date to the thirteenth century, in a specialized “salle de soutenance” constructed in the nineteenth. The defendant was made to sit at a small desk beneath a looming podium, where we, the honorable members of the jury, were solemnly seated. The borrowed vocabulary from the world of the criminal trial is intentional and unmistakable. As usual I tried to play my part and look as grim and serious as possible. I confess I find it fairly easy, at least for a short time, to get swept up by the spirit of such rituals. For Shah, migration has always been the rule rather than the exception, but it will become even more common as the planet warms. The low-lying country of Bangladesh has a population of more than 150 million. If the seas rise three feet—quite likely to happen this century—a fifth of its land, on which some 30 million people live, will be submerged. Those 30 million will be forced to move, and when they do, it will matter how they’re regarded. As “Bangladeshis” perpetually out of place, they will likely struggle to find safe berth. It would be better, Shah suggests, to drop the labels, recognize human beings as a migratory species, and build institutions around that fact.

For Shah, migration has always been the rule rather than the exception, but it will become even more common as the planet warms. The low-lying country of Bangladesh has a population of more than 150 million. If the seas rise three feet—quite likely to happen this century—a fifth of its land, on which some 30 million people live, will be submerged. Those 30 million will be forced to move, and when they do, it will matter how they’re regarded. As “Bangladeshis” perpetually out of place, they will likely struggle to find safe berth. It would be better, Shah suggests, to drop the labels, recognize human beings as a migratory species, and build institutions around that fact.