Adam Tooze over at Substack:

I was forced to talk about bitcoin this week. On a podcast (in German).

The discussion was triggered by the remarkable surge in bitcoin’s value – the second great surge in the Ur-crypto’s turbulent history since it’s launch on 3 January 2009.

Lisa Splanemann, the journalist with whom I do the podcast, has been pushing the topic for a while. I was reluctant.

Money talk is political talk. We should be selective in the political talk we engage in. I don’t like the politics of crypto/bitcoin.

Money is an expression of social power. In particular, it is an amalgam of the power and confidence leveraged by the state and capital. All actual monies, whatever form they are cast in, have an element of “fiat” about them.

As the Merriman-Webster dictionary helpfully explains: “fiat: a command or act of will that creates something without or as if without further effort. According to the Bible, the world was created by fiat.”

The fiat money world is the world that we have inhabited since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system between 1971 and 1973. It is normally contrasted to the gold standard world that preceded it. But are gold and “fiat” really that different? To back a currency with gold is a political choice too, anchored in structures of expectation on the part of creditors, debtors and investors, on systems for gold production, storage, relationships between banks and central banks, in other words structures of power.

More here.

We don’t read diarists because we admire them, but because they were there, and they note down what they saw and heard. “Chips” Channon was wrong about almost everything. But do we read Boswell, Casanova, Pepys, Alan Clark or even Sasha Swire for their judgement? We do not. We read them to be taken aback, and to question ourselves. Exhausting, massive, genuinely shocking, and still revelatory, this new edition of the Channon diaries is a work of irrigation and genuine scholarship. Few people may read them from cover to cover, but the stories they contain will rattle noisily around our culture for decades ahead.

We don’t read diarists because we admire them, but because they were there, and they note down what they saw and heard. “Chips” Channon was wrong about almost everything. But do we read Boswell, Casanova, Pepys, Alan Clark or even Sasha Swire for their judgement? We do not. We read them to be taken aback, and to question ourselves. Exhausting, massive, genuinely shocking, and still revelatory, this new edition of the Channon diaries is a work of irrigation and genuine scholarship. Few people may read them from cover to cover, but the stories they contain will rattle noisily around our culture for decades ahead.

On 7 March 1965, the nation came to grips with one of the most iconic images synonymous with the fight for voting rights and equality.

On 7 March 1965, the nation came to grips with one of the most iconic images synonymous with the fight for voting rights and equality.  For the mathematician Sarah Hart, a close reading of “Moby-Dick” reveals not merely (per D.H. Lawrence) “one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world” and “the greatest book of the sea ever written,” but also a work awash in mathematical metaphors. “Herman Melville, he really liked mathematics — you can see it in his books,” said Dr. Hart, a professor at Birkbeck, University of London, during a February talk on “

For the mathematician Sarah Hart, a close reading of “Moby-Dick” reveals not merely (per D.H. Lawrence) “one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world” and “the greatest book of the sea ever written,” but also a work awash in mathematical metaphors. “Herman Melville, he really liked mathematics — you can see it in his books,” said Dr. Hart, a professor at Birkbeck, University of London, during a February talk on “ A lost poem by

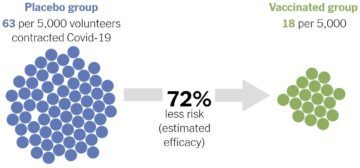

A lost poem by  Efficacy is a crucial concept in vaccine trials, but it’s also a tricky one. If a vaccine has an efficacy of, say, 95 percent, that doesn’t mean that 5 percent of people who receive that vaccine will get Covid-19. And just because one vaccine ends up with a higher efficacy estimate than another in trials doesn’t necessarily mean it’s superior. Here’s why.

Efficacy is a crucial concept in vaccine trials, but it’s also a tricky one. If a vaccine has an efficacy of, say, 95 percent, that doesn’t mean that 5 percent of people who receive that vaccine will get Covid-19. And just because one vaccine ends up with a higher efficacy estimate than another in trials doesn’t necessarily mean it’s superior. Here’s why. More than two decades after the country democratized, a sense of insecurity persists in daily life in South Africa, and access to the public good of security has remained astonishingly unequal. In lieu of equitable access to security, affluent neighborhoods are adorned with nine-foot cement walls, expandable steel security gates, and armed guards. Even the state itself employs private security officers, hiring private guards to patrol the outside of police precincts and to carry out unseemly land evictions. Private security in South Africa is like a snake eating its own tail, as the government itself invests in the firms that are undermining its own authority.

More than two decades after the country democratized, a sense of insecurity persists in daily life in South Africa, and access to the public good of security has remained astonishingly unequal. In lieu of equitable access to security, affluent neighborhoods are adorned with nine-foot cement walls, expandable steel security gates, and armed guards. Even the state itself employs private security officers, hiring private guards to patrol the outside of police precincts and to carry out unseemly land evictions. Private security in South Africa is like a snake eating its own tail, as the government itself invests in the firms that are undermining its own authority. In 1966, a young American journalist named Frances FitzGerald began publishing articles from South Vietnam in leading magazines, including this one. She was the unlikeliest of war correspondents—born into immense privilege, a daughter of the high-WASP ascendancy. Her father, Desmond FitzGerald, was a top CIA official; her mother, Marietta Tree, a socialite and liberal activist. FitzGerald was raised with servants and horses, and she had to fend off advances from the likes of Adlai Stevenson (her mother’s lover) and Henry Kissinger. Her family contacts got her through the door of feature journalism in New York, but as a woman, she was denied the chance to pursue the serious work she wanted to do. She escaped this jeweled trap by making her own way to Saigon at age 25, just as the American war was escalating.

In 1966, a young American journalist named Frances FitzGerald began publishing articles from South Vietnam in leading magazines, including this one. She was the unlikeliest of war correspondents—born into immense privilege, a daughter of the high-WASP ascendancy. Her father, Desmond FitzGerald, was a top CIA official; her mother, Marietta Tree, a socialite and liberal activist. FitzGerald was raised with servants and horses, and she had to fend off advances from the likes of Adlai Stevenson (her mother’s lover) and Henry Kissinger. Her family contacts got her through the door of feature journalism in New York, but as a woman, she was denied the chance to pursue the serious work she wanted to do. She escaped this jeweled trap by making her own way to Saigon at age 25, just as the American war was escalating. Everyone seems to be talking about the problems with physics: Peter Woit’s book Not Even Wrong, Lee Smolin’s The Trouble With Physics, and Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math leap to mind, and they have started a wider conversation. But is all of physics really in trouble, or just some of it? If you actually read these books, you’ll see they’re about so-called “fundamental” physics. Some other parts of physics are doing just fine, and I want to tell you about one. It’s called “condensed matter physics,” and it’s the study of solids and liquids. We are living in the golden age of condensed matter physics.

Everyone seems to be talking about the problems with physics: Peter Woit’s book Not Even Wrong, Lee Smolin’s The Trouble With Physics, and Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math leap to mind, and they have started a wider conversation. But is all of physics really in trouble, or just some of it? If you actually read these books, you’ll see they’re about so-called “fundamental” physics. Some other parts of physics are doing just fine, and I want to tell you about one. It’s called “condensed matter physics,” and it’s the study of solids and liquids. We are living in the golden age of condensed matter physics. A mutating virus is destroying a world-view that has ruled governments, business and popular culture for a century or more. A model in which humankind was achieving ever higher levels of control over the planet has shaped much of modern thinking. Evolution has been understood as the ascent from primeval slime to unchallengeable human dominance over all other forms of life. Fundamentally at odds with the theory of natural selection, this was never more than pseudo-science. Yet from the late 19th century onwards it became a ruling paradigm, captivating generations of thinkers and inspiring world-changing political movements. Today the myth is crumbling. For the first time in history, using genomic sequencing, natural selection is being observed, in detail and real time, at the level of genes. Evolution is continuing, rapidly, with the virus as the chief protagonist.

A mutating virus is destroying a world-view that has ruled governments, business and popular culture for a century or more. A model in which humankind was achieving ever higher levels of control over the planet has shaped much of modern thinking. Evolution has been understood as the ascent from primeval slime to unchallengeable human dominance over all other forms of life. Fundamentally at odds with the theory of natural selection, this was never more than pseudo-science. Yet from the late 19th century onwards it became a ruling paradigm, captivating generations of thinkers and inspiring world-changing political movements. Today the myth is crumbling. For the first time in history, using genomic sequencing, natural selection is being observed, in detail and real time, at the level of genes. Evolution is continuing, rapidly, with the virus as the chief protagonist.

Branko Milanovic in Foreign Affairs:

Branko Milanovic in Foreign Affairs: Jane Hu in Bookforum:

Jane Hu in Bookforum: Joanna Wuest in Psyche:

Joanna Wuest in Psyche: AMONG THE MANY ENTRIES in Edwin Frank’s increasingly encyclopedic New York Review Books Classics series is a genre of postwar European memoir: informed by psychoanalysis, ironic in tone or form, and of subject matter that’s both bourgeois and aristocratic—or at the intersections where upwardly moving middle classes and downwardly mobile inherited scions most resemble each other. Gregor von Rezzori’s Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, J. R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself, Jessica Mitford’s Hons and Rebels: these books record their authors’ efforts to collect the pieces and resolve mysteries of their childhoods and adolescence—a task often complicated by the shattering impact of the Second World War—and have also become documents in their own right, testaments not only to a bygone world but to a bygone way of reckoning with privilege, secrets, desire, belonging, and money. Richard Wollheim’s Germs, first published posthumously in 2004, hits all these notes: his parents’ somewhat open marriage, his lower-class granny, his immersion in a milieu of genuine artists, appreciators, and pompous hucksters and hustlers, sometimes united in the same person. Wollheim was still fine-tuning the manuscript when he died in 2003, at eighty, and what we have is mostly organized around the childhood and adolescent years before he arrived at Oxford, though with occasional associative leaps forward and backward in time.

AMONG THE MANY ENTRIES in Edwin Frank’s increasingly encyclopedic New York Review Books Classics series is a genre of postwar European memoir: informed by psychoanalysis, ironic in tone or form, and of subject matter that’s both bourgeois and aristocratic—or at the intersections where upwardly moving middle classes and downwardly mobile inherited scions most resemble each other. Gregor von Rezzori’s Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, J. R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself, Jessica Mitford’s Hons and Rebels: these books record their authors’ efforts to collect the pieces and resolve mysteries of their childhoods and adolescence—a task often complicated by the shattering impact of the Second World War—and have also become documents in their own right, testaments not only to a bygone world but to a bygone way of reckoning with privilege, secrets, desire, belonging, and money. Richard Wollheim’s Germs, first published posthumously in 2004, hits all these notes: his parents’ somewhat open marriage, his lower-class granny, his immersion in a milieu of genuine artists, appreciators, and pompous hucksters and hustlers, sometimes united in the same person. Wollheim was still fine-tuning the manuscript when he died in 2003, at eighty, and what we have is mostly organized around the childhood and adolescent years before he arrived at Oxford, though with occasional associative leaps forward and backward in time.