Laura Cumming in The Guardian:

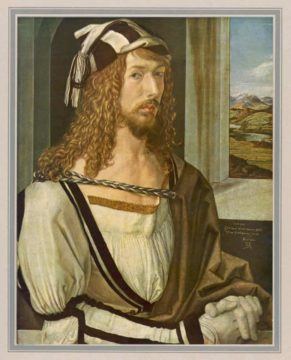

Albrecht Dürer was the first great sightseer in the history of art, travelling Europe to see conjoined twins, Aztec gold, Venetian gondolas and the bones of an 18ft giant. He crossed the Alps more than once and voyaged for six days in the freezing winter of 1520 to see a whale on a beach in Zeeland. The ship was nearly wrecked, but somehow Dürer saved the day and they eventually reached the shore. The sands were empty. The great creature had sailed away.

Albrecht Dürer was the first great sightseer in the history of art, travelling Europe to see conjoined twins, Aztec gold, Venetian gondolas and the bones of an 18ft giant. He crossed the Alps more than once and voyaged for six days in the freezing winter of 1520 to see a whale on a beach in Zeeland. The ship was nearly wrecked, but somehow Dürer saved the day and they eventually reached the shore. The sands were empty. The great creature had sailed away.

This magnificent new book by Philip Hoare takes its title from that tale, but only as a point of departure. The narrative soon turns into a trip of another kind entirely, a captivating journey through art and life, nature and human nature, biography and personal memoir. Giants walk the earth: Dürer and Martin Luther, Shakespeare and Blake, Thomas Mann, Marianne Moore, WH Auden, David Bowie. Hoare summons them like Prospero, his writing the animating magic that brings the people of the past directly into our present and unleashes spectacular visions along the way.

Just to follow him to that same beach in Zeeland, for instance, is to be entranced by his descriptions of deserted ports, windblown flatlands and shadowy waters. Hoare sees the creatures Dürer never saw, as if on his behalf. He offers the poignant revelation that the giant’s bones were actually those of a bowhead whale, knowing what it would have meant to the artist. Shown the day’s catch in a local restaurant, he marvels at the orange spots on the glistening brown plaice – “the fingerprints of a saint” – and imagines Dürer immediately drawing the fish on his napkin. Both men are present in that moment; both of Hoare’s pictures are perfect.

More here.

If you were somehow able to travel back in time some 130,000 years and chance upon a Neanderthal, you might find yourself telling them about some of humanity’s greatest inventions, such as spanakopita and TikTok. The Neanderthal would have no idea what you were saying, much less talking about, but they might be able to hear you perfectly, picking up on the voiceless consonants “t,” “k” and “s” that appear in many modern human languages. A team of scientists has reconstructed the outer and middle ear of Neanderthals and concluded that they listened to the world much like we do. Their

If you were somehow able to travel back in time some 130,000 years and chance upon a Neanderthal, you might find yourself telling them about some of humanity’s greatest inventions, such as spanakopita and TikTok. The Neanderthal would have no idea what you were saying, much less talking about, but they might be able to hear you perfectly, picking up on the voiceless consonants “t,” “k” and “s” that appear in many modern human languages. A team of scientists has reconstructed the outer and middle ear of Neanderthals and concluded that they listened to the world much like we do. Their

Scientists have come up with a computer program that can master a variety of 1980s exploration games, paving the way for more self-sufficient robots.

Scientists have come up with a computer program that can master a variety of 1980s exploration games, paving the way for more self-sufficient robots. Last spring,

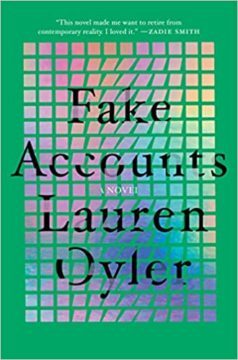

Last spring,  Since its consolidation at the end of the eighteenth century, the realist novel has been the premier vehicle for the depiction of contemporary life. For over two hundred years, a relatively fixed set of representational techniques – point-of-view, voice, description, dialogue, plot – has managed to adapt to the radical transformations of modernity: the nuclearization of the family, the entry of women into public life, the liberalization of sexual mores, industrialization and deindustrialization, urbanization and suburbanization, secularization, the lifeworlds of dominated classes and colonized nations, war on a planetary scale, and new conceptions of cognition and identity formation, to name just a few. By doubling down on its core strength – the linguistic representation of inner experience – the novel even managed to fend off challenges from rival media, like film and television. But over the last decade or so it has become clear that changes in the texture of the contemporary itself, due primarily to the diffusion of digital networked media, have begun to strain the capacity of the novel – as an institution, as a medium, as a form – to fulfil its traditional remit.

Since its consolidation at the end of the eighteenth century, the realist novel has been the premier vehicle for the depiction of contemporary life. For over two hundred years, a relatively fixed set of representational techniques – point-of-view, voice, description, dialogue, plot – has managed to adapt to the radical transformations of modernity: the nuclearization of the family, the entry of women into public life, the liberalization of sexual mores, industrialization and deindustrialization, urbanization and suburbanization, secularization, the lifeworlds of dominated classes and colonized nations, war on a planetary scale, and new conceptions of cognition and identity formation, to name just a few. By doubling down on its core strength – the linguistic representation of inner experience – the novel even managed to fend off challenges from rival media, like film and television. But over the last decade or so it has become clear that changes in the texture of the contemporary itself, due primarily to the diffusion of digital networked media, have begun to strain the capacity of the novel – as an institution, as a medium, as a form – to fulfil its traditional remit. During a rare excursion to a clothes shop I took last month, an older woman walked in, looked around at the other shoppers and exclaimed, “humans!” It was an unusual moment of bonding with strangers. Mostly I just hold my breath as people squeeze past me at the supermarket. In this year of staying two metres away from practically everyone, we’ve all become used to treating other people as potentially toxic. Now that vaccinations are under way, we’re allowed to hope that we will one day emerge from hibernation. What will socialising be like on the other side? And how will we cope with being together again?

During a rare excursion to a clothes shop I took last month, an older woman walked in, looked around at the other shoppers and exclaimed, “humans!” It was an unusual moment of bonding with strangers. Mostly I just hold my breath as people squeeze past me at the supermarket. In this year of staying two metres away from practically everyone, we’ve all become used to treating other people as potentially toxic. Now that vaccinations are under way, we’re allowed to hope that we will one day emerge from hibernation. What will socialising be like on the other side? And how will we cope with being together again? Black History Month has been celebrated in the United States for close to 100 years. But what is it, exactly, and how did it begin?

Black History Month has been celebrated in the United States for close to 100 years. But what is it, exactly, and how did it begin? Joshua Cohen in Boston Review:

Joshua Cohen in Boston Review: Jamie McCallum in Aeon:

Jamie McCallum in Aeon: Elizabeth Anderson in The Nation:

Elizabeth Anderson in The Nation: Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire in The Atlantic:

Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire in The Atlantic: The Believer is the highly anticipated second book from Sarah Krasnostein, author of multi-award-winning

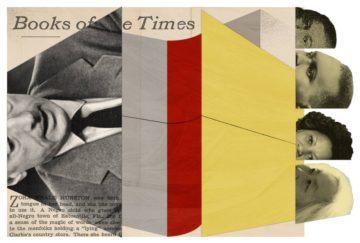

The Believer is the highly anticipated second book from Sarah Krasnostein, author of multi-award-winning  To wander through 125 years of book reviews is to endure assault by adjective. All the fatuous books, the frequently brilliant, the disappointing, the essential. The adjectives one only ever encounters in a review (indelible, risible), the archaic descriptors (sumptuous). So many masterpieces, so many duds — now enjoying quiet anonymity.

To wander through 125 years of book reviews is to endure assault by adjective. All the fatuous books, the frequently brilliant, the disappointing, the essential. The adjectives one only ever encounters in a review (indelible, risible), the archaic descriptors (sumptuous). So many masterpieces, so many duds — now enjoying quiet anonymity.