Richard Haass in Project Syndicate:

The report issued Friday by the US intelligence community on the murder of Saudi journalist and permanent US resident Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018 at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey mostly confirms what we already knew. The operation to capture or kill Khashoggi was approved by Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince and in many ways already the Kingdom’s most powerful person. MBS, as he is widely known, wanted Khashoggi dead, both to rid himself of a nettlesome critic and to intimidate other would-be critics of his rule.

We are unlikely to find a smoking gun, but MBS’s fingerprints are all over Khashoggi’s killing. There is not only abundant photographic and communications evidence that it was carried out by people close to the Crown Prince. There is also the simple reality that nothing of significant political magnitude happens in Saudi Arabia without MBS’s authorization.

Former President Donald Trump’s administration looked the other way at the time, as it often did in the face of flagrant human rights violations. Moreover, Trump wanted to avoid a rupture with MBS, whose anti-Iranian policies were appreciated and who was seen as central to his government’s willingness to purchase armaments from US manufacturers.

President Joe Biden’s administration feels differently. It has already distanced the United States from involvement in Saudi military operations in Yemen. And human rights are occupying a central role in its approach to the world. The fact that Biden has not communicated directly with MBS, and instead called the ailing King Salman, underscores Biden’s desire to separate the US relationship with the Kingdom from the relationship with the Crown Prince.

But this separation will likely prove impossible to sustain.

More here.

On a road into New Delhi, countless cars a day speed over tonnes of plastic bags, bottle tops and discarded polystyrene cups. In a single kilometre, a driver covers one tonne of plastic waste. But far from being an unpleasant journey through a sea of litter, this road is smooth and well-maintained – in fact the plastic that each driver passes over isn’t visible to the naked eye. It is simply a part of the road. This road, stretching from New Delhi to nearby Meerut, was laid using a system developed by Rajagopalan Vasudevan, a professor of chemistry at the Thiagarajar College of Engineering in India, which replaces 10% of a road’s bitumen with repurposed plastic waste.

On a road into New Delhi, countless cars a day speed over tonnes of plastic bags, bottle tops and discarded polystyrene cups. In a single kilometre, a driver covers one tonne of plastic waste. But far from being an unpleasant journey through a sea of litter, this road is smooth and well-maintained – in fact the plastic that each driver passes over isn’t visible to the naked eye. It is simply a part of the road. This road, stretching from New Delhi to nearby Meerut, was laid using a system developed by Rajagopalan Vasudevan, a professor of chemistry at the Thiagarajar College of Engineering in India, which replaces 10% of a road’s bitumen with repurposed plastic waste. When Eugen Sandow (pictured) opened his first School of Physical Culture in London in the summer of 1897, he ensured that its decor matched his personal brand. On arrival at 32A St James’s Street, visitors found themselves facing a life-sized statue of the founder himself. A nearby oil painting depicted Sandow as an ancient gladiator. In both cases his sculpted physique evoked the spirit of Greek classicism that Sandow, regarded in his heyday as the “perfect man”, strove to embody.

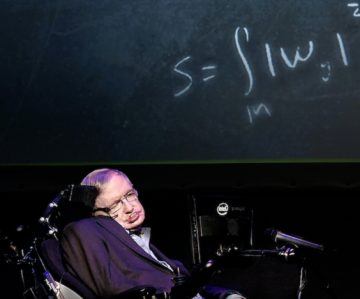

When Eugen Sandow (pictured) opened his first School of Physical Culture in London in the summer of 1897, he ensured that its decor matched his personal brand. On arrival at 32A St James’s Street, visitors found themselves facing a life-sized statue of the founder himself. A nearby oil painting depicted Sandow as an ancient gladiator. In both cases his sculpted physique evoked the spirit of Greek classicism that Sandow, regarded in his heyday as the “perfect man”, strove to embody. In one of his 2016 Reith Lectures, Stephen Hawking said an odd thing. “People have searched for mini black holes… but have so far not found any,” he intoned with his trademark voice synthesiser. “This is a pity, because if they had I would have got a Nobel Prize.” The audience at the Royal Institution in London (which included me) laughed. But I was struck by how unusual it was for a scientist to state publicly that their work warranted a Nobel. It was no passing comment. A few minutes later, Hawking described how mini black holes—which he predicted in the early 1970s—might yet be seen in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Geneva. “So I might get a Nobel Prize after all,” he added, to more laughter.

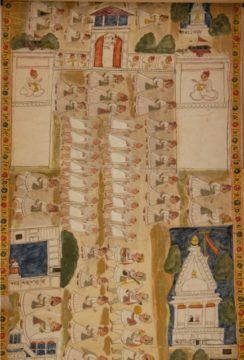

In one of his 2016 Reith Lectures, Stephen Hawking said an odd thing. “People have searched for mini black holes… but have so far not found any,” he intoned with his trademark voice synthesiser. “This is a pity, because if they had I would have got a Nobel Prize.” The audience at the Royal Institution in London (which included me) laughed. But I was struck by how unusual it was for a scientist to state publicly that their work warranted a Nobel. It was no passing comment. A few minutes later, Hawking described how mini black holes—which he predicted in the early 1970s—might yet be seen in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Geneva. “So I might get a Nobel Prize after all,” he added, to more laughter. I first encountered a snippet of the seventy-two-foot-long painted invitation letter as a four by six-inch reproduction in Susan Gole’s pioneering Indian Maps and Plans (New Delhi: Manohar, 54). No measurements were noted. Yet, I imagined the scroll’s spread—it motivated me to abandon archival research in the British Library and travel to Bikaner at short notice in April 2009. Housed in the Abhay Jain Granthalaya, maintained as the personal library of the renowned scholar of Jain religion and culture, Dr. Abhaychand Nahata, I never anticipated the extent to which this artifact would impact my research. As the librarian, Mr. Chopra, helped me carefully unfurl the scroll, held together by a spindle on either end in an openable glass box, Udaipur’s painted streets, shops, and sights were revealed. At any given instance, I could examine only a two-foot section of the scroll. I attempted to retain the painted vignette past my line of vision just as we stack storefronts in our memory while walking through a busy bazaar. Similarly, the composite image, presented within the rectangular window of the

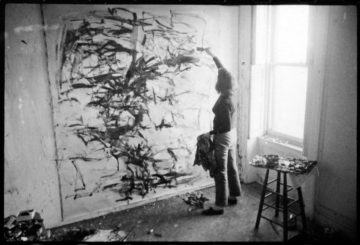

I first encountered a snippet of the seventy-two-foot-long painted invitation letter as a four by six-inch reproduction in Susan Gole’s pioneering Indian Maps and Plans (New Delhi: Manohar, 54). No measurements were noted. Yet, I imagined the scroll’s spread—it motivated me to abandon archival research in the British Library and travel to Bikaner at short notice in April 2009. Housed in the Abhay Jain Granthalaya, maintained as the personal library of the renowned scholar of Jain religion and culture, Dr. Abhaychand Nahata, I never anticipated the extent to which this artifact would impact my research. As the librarian, Mr. Chopra, helped me carefully unfurl the scroll, held together by a spindle on either end in an openable glass box, Udaipur’s painted streets, shops, and sights were revealed. At any given instance, I could examine only a two-foot section of the scroll. I attempted to retain the painted vignette past my line of vision just as we stack storefronts in our memory while walking through a busy bazaar. Similarly, the composite image, presented within the rectangular window of the  THE CANVAS IS LARGE, standing more than seven feet tall and six feet wide. Painted on a white ground, the composition reveals numerous areas in which white paint has been energetically brushed over marks in other colors, progressively editing a roiling chaos of gestures down to a sparer, more defined structure with several especially prominent elements. In the upper register, just left of center, overlapping brushstrokes in shades of red, black, blue-green, and yellow combine to form a thick vertical line, as if marking out the operative axis. Just below this upright element, there appears a dense flurry of multicolored gestures. Clustered in a roughly horizontal zone, this array tapers to either side but is both extended and visually weighted toward the right. Also on the right, a bit farther down, dozens of brushstrokes have again been layered one atop the other, creating a diagonal band. At the very bottom of the picture, yet another cluster of predominantly oblique gestures form a rough wedge, drawing the eye to the lower right. The artist has signed her first initial and last name: J. MITCHELL.

THE CANVAS IS LARGE, standing more than seven feet tall and six feet wide. Painted on a white ground, the composition reveals numerous areas in which white paint has been energetically brushed over marks in other colors, progressively editing a roiling chaos of gestures down to a sparer, more defined structure with several especially prominent elements. In the upper register, just left of center, overlapping brushstrokes in shades of red, black, blue-green, and yellow combine to form a thick vertical line, as if marking out the operative axis. Just below this upright element, there appears a dense flurry of multicolored gestures. Clustered in a roughly horizontal zone, this array tapers to either side but is both extended and visually weighted toward the right. Also on the right, a bit farther down, dozens of brushstrokes have again been layered one atop the other, creating a diagonal band. At the very bottom of the picture, yet another cluster of predominantly oblique gestures form a rough wedge, drawing the eye to the lower right. The artist has signed her first initial and last name: J. MITCHELL. IT’S ONE OF THE MIGHTIEST RIVERS you will never see, carrying some 30 times more water than all the world’s freshwater rivers combined. In the North Atlantic, one arm of the Gulf Stream breaks toward Iceland, transporting vast amounts of warmth far northward, by one estimate supplying Scandinavia with heat equivalent to 78,000 times its current energy use. Without this current — a heat pump on a planetary scale — scientists believe that great swathes of the world might look quite different.

IT’S ONE OF THE MIGHTIEST RIVERS you will never see, carrying some 30 times more water than all the world’s freshwater rivers combined. In the North Atlantic, one arm of the Gulf Stream breaks toward Iceland, transporting vast amounts of warmth far northward, by one estimate supplying Scandinavia with heat equivalent to 78,000 times its current energy use. Without this current — a heat pump on a planetary scale — scientists believe that great swathes of the world might look quite different. It sounds like the plot of some cop-buddy movie: an anarchic hippie social worker (Snoop Dogg or Owen Wilson) is forced to team up with a straight-laced conservative cop (Clint Eastwood, the Rock). Chaos and hilarity ensue. Life lessons are learned. In this case, it actually happened.

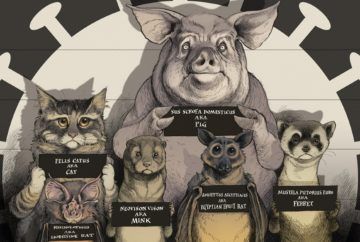

It sounds like the plot of some cop-buddy movie: an anarchic hippie social worker (Snoop Dogg or Owen Wilson) is forced to team up with a straight-laced conservative cop (Clint Eastwood, the Rock). Chaos and hilarity ensue. Life lessons are learned. In this case, it actually happened. It was the news Sophie Gryseels had been dreading for months. Almost a year into the pandemic, a seemingly healthy wild mink tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Utah. No free-roaming animal was known to have caught the virus before, although researchers had been watching for this closely. “It’s happened,” wrote Gryseels, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, in an e-mail to her colleagues. Ever since the coronavirus started spreading around the world, scientists have worried that it could leap from people into wild animals. If so, it might lurk in various species, possibly mutate and then resurge in humans even after the pandemic has subsided.

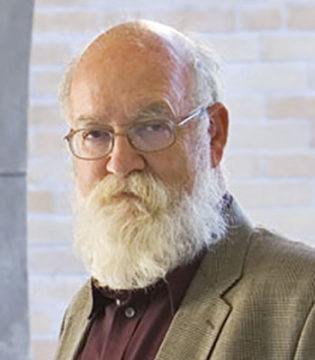

It was the news Sophie Gryseels had been dreading for months. Almost a year into the pandemic, a seemingly healthy wild mink tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Utah. No free-roaming animal was known to have caught the virus before, although researchers had been watching for this closely. “It’s happened,” wrote Gryseels, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, in an e-mail to her colleagues. Ever since the coronavirus started spreading around the world, scientists have worried that it could leap from people into wild animals. If so, it might lurk in various species, possibly mutate and then resurge in humans even after the pandemic has subsided. Causation and control are not the same thing. Not all things that are caused are controlled. Things that are controlled are caused, like everything else, but control requires a controller, an agent of sorts designed to control a process, and that requires feedback: information about the trajectory and conditions that can be used by the controller to modulate the action. This is a fundamental point of control theory. Think about firing a rifle bullet. You’re controlling the direction of the gun barrel and, with the trigger, the time of the bullet emerging from the gun barrel. Are you controlling the course of the bullet after that? No. Where it goes after it leaves the muzzle is out of your control. Now, if you’re a really good shot, you may be able to calculate in advance the windage and so forth and you may be able to get it in the bull’s eye almost every time. But you are unable to affect the trajectory of the bullet after it leaves the gun. So it is not a controlled trajectory, it is a ballistic trajectory. It goes where it goes and, if your eyes were good enough to watch it and see that it was going “off course,” you’d have feedback, but you wouldn’t be able to do anything about it. Feedback is only useful information coming back to a controller if the controller also maintains an informational link back to the thing that’s being controlled. You fired the gun. You caused that bullet to go where it went, but you did not control the bullet after it left the gun. Compare that with a guided missile. A guided missile, after it’s launched, can still be controlled, to some extent, often to a great extent (as in a cruise missile). As you know, one of the chief inventions of technology in warfare in the last fifty years is the development of remote control missiles and, of course, remote control drones. Remote control is real, and readily distinguished from out of control. Autonomy is non-remote control, local or internal control, and it is just as real, and even more important.

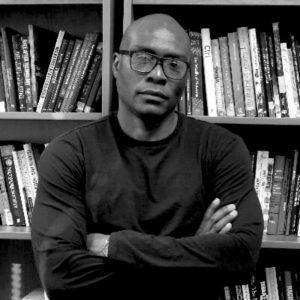

Causation and control are not the same thing. Not all things that are caused are controlled. Things that are controlled are caused, like everything else, but control requires a controller, an agent of sorts designed to control a process, and that requires feedback: information about the trajectory and conditions that can be used by the controller to modulate the action. This is a fundamental point of control theory. Think about firing a rifle bullet. You’re controlling the direction of the gun barrel and, with the trigger, the time of the bullet emerging from the gun barrel. Are you controlling the course of the bullet after that? No. Where it goes after it leaves the muzzle is out of your control. Now, if you’re a really good shot, you may be able to calculate in advance the windage and so forth and you may be able to get it in the bull’s eye almost every time. But you are unable to affect the trajectory of the bullet after it leaves the gun. So it is not a controlled trajectory, it is a ballistic trajectory. It goes where it goes and, if your eyes were good enough to watch it and see that it was going “off course,” you’d have feedback, but you wouldn’t be able to do anything about it. Feedback is only useful information coming back to a controller if the controller also maintains an informational link back to the thing that’s being controlled. You fired the gun. You caused that bullet to go where it went, but you did not control the bullet after it left the gun. Compare that with a guided missile. A guided missile, after it’s launched, can still be controlled, to some extent, often to a great extent (as in a cruise missile). As you know, one of the chief inventions of technology in warfare in the last fifty years is the development of remote control missiles and, of course, remote control drones. Remote control is real, and readily distinguished from out of control. Autonomy is non-remote control, local or internal control, and it is just as real, and even more important. The internet has made it so much easier for people to talk to each other, in a literal sense. But it hasn’t necessarily made it easier to have rewarding, productive, good-faith conversations. Here I talk with sociologist Rod Graham about what kinds of conversations the internet does enable, and should enable, and how we can work to make them better. We discuss both how social media are used for nefarious purposes, from cyberbullying to driving extremism, but also how they can be mobilized for more lofty goals. We also get into some of the lost nuances in conventional discussions of race, including how many minorities are more culturally conservative than an oversimplified narrative would lead us to believe, and the tricky relationship between online discourse and social cohesion.

The internet has made it so much easier for people to talk to each other, in a literal sense. But it hasn’t necessarily made it easier to have rewarding, productive, good-faith conversations. Here I talk with sociologist Rod Graham about what kinds of conversations the internet does enable, and should enable, and how we can work to make them better. We discuss both how social media are used for nefarious purposes, from cyberbullying to driving extremism, but also how they can be mobilized for more lofty goals. We also get into some of the lost nuances in conventional discussions of race, including how many minorities are more culturally conservative than an oversimplified narrative would lead us to believe, and the tricky relationship between online discourse and social cohesion.

In Ferrante’s most recent novel, The Lying Life of Adults, we are pulled yet again into the story with the tale of a missing woman, Aunt Vittoria. Unlike Lila, she has not disappeared altogether but is estranged from her brother, Andrea, and her 12-year-old niece, Giovanna, who narrates the story. While Giovanna and her parents live in a middle-class section of Naples, Vittoria has remained in Pascone, the working-class neighborhood in the city’s Industrial Zone where she and Andrea were raised. Throughout the novel, we get conflicting stories from Vittoria and Andrea about what led to their estrangement. A dispute about who should inherit their mother’s apartment following her death was certainly the breaking point, but there had long been tension between them. Early on, it becomes clear that Andrea is frustrated that his sister did not respond to the poverty of their childhood in the same way he did: by leaving Pascone behind with no qualms or doubts and embracing the tastes and habits of the Italian bourgeoisie. But what takes longer to be revealed is that Vittoria is perhaps no better, that her working-class pride may not be as sturdy as she wants her young, wide-eyed niece to think.

In Ferrante’s most recent novel, The Lying Life of Adults, we are pulled yet again into the story with the tale of a missing woman, Aunt Vittoria. Unlike Lila, she has not disappeared altogether but is estranged from her brother, Andrea, and her 12-year-old niece, Giovanna, who narrates the story. While Giovanna and her parents live in a middle-class section of Naples, Vittoria has remained in Pascone, the working-class neighborhood in the city’s Industrial Zone where she and Andrea were raised. Throughout the novel, we get conflicting stories from Vittoria and Andrea about what led to their estrangement. A dispute about who should inherit their mother’s apartment following her death was certainly the breaking point, but there had long been tension between them. Early on, it becomes clear that Andrea is frustrated that his sister did not respond to the poverty of their childhood in the same way he did: by leaving Pascone behind with no qualms or doubts and embracing the tastes and habits of the Italian bourgeoisie. But what takes longer to be revealed is that Vittoria is perhaps no better, that her working-class pride may not be as sturdy as she wants her young, wide-eyed niece to think. The interviewers often push Girard to explain how his theory applies to real life, and he is happy to oblige. The theory’s journey into the world is a great story in its own right. No sooner did his argument reach a certain “elegance” than Girard started to realize its growing applicability: “You suddenly see that there is a single explanation for a thousand different phenomena.” He first formulated his theory in a book of literary history, then went on to apply it to the study of mythology and religion, then to politics and international relations, then to society and economy, fashion and eating disorders, and whatnot. Just open a newspaper and pick something, anything, at random. Even the stock market? Especially the stock market, Girard would respond. That’s “the most mimetic institution” of all—indeed, a textbook illustration of how mimetic theory works: “You desire stock not because it is objectively desirable. You know nothing about it, but you desire stuff exclusively because other people desire it. And if other people desire it, its value goes up and up and up.” There is hardly a field, sphere of life, or situation, where Girard’s theory does not apply. He finds that fascinating. Some of his readers find it too good to be true. Others find it scandalous.

The interviewers often push Girard to explain how his theory applies to real life, and he is happy to oblige. The theory’s journey into the world is a great story in its own right. No sooner did his argument reach a certain “elegance” than Girard started to realize its growing applicability: “You suddenly see that there is a single explanation for a thousand different phenomena.” He first formulated his theory in a book of literary history, then went on to apply it to the study of mythology and religion, then to politics and international relations, then to society and economy, fashion and eating disorders, and whatnot. Just open a newspaper and pick something, anything, at random. Even the stock market? Especially the stock market, Girard would respond. That’s “the most mimetic institution” of all—indeed, a textbook illustration of how mimetic theory works: “You desire stock not because it is objectively desirable. You know nothing about it, but you desire stuff exclusively because other people desire it. And if other people desire it, its value goes up and up and up.” There is hardly a field, sphere of life, or situation, where Girard’s theory does not apply. He finds that fascinating. Some of his readers find it too good to be true. Others find it scandalous.