Stephen Law in Psyche:

These squiggles have a meaning. So do spoken words, road signs, mathematical equations and signal flags. Meaning is something with which we’re intimately familiar – so familiar that, for the most part, we barely register or think about it at all. And yet, once we do begin to reflect on meaning, it can quickly begin to seem bizarre and even magical. How can a few marks on a sheet of paper reach out across time to refer to a person long dead? How can a mere sound in the air instantaneously pick out a galaxy light-years away? What gives words these extraordinary powers? The answer, of course, is that we do. But how?

These squiggles have a meaning. So do spoken words, road signs, mathematical equations and signal flags. Meaning is something with which we’re intimately familiar – so familiar that, for the most part, we barely register or think about it at all. And yet, once we do begin to reflect on meaning, it can quickly begin to seem bizarre and even magical. How can a few marks on a sheet of paper reach out across time to refer to a person long dead? How can a mere sound in the air instantaneously pick out a galaxy light-years away? What gives words these extraordinary powers? The answer, of course, is that we do. But how?

A slogan often associated with the later philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) is ‘meaning is use’. Here’s what Wittgenstein actually says:

For a large class of cases of the employment of the word ‘meaning’ – though not for all – this word can be explained in this way: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.

In order to appreciate the philosophical significance of this remark, let’s begin by looking at one of the key things that Wittgenstein is warning us against.

Suppose I say: ‘It’s hot today.’ So does a parrot. Saying the words is a process; for example, it can be done quickly or slowly.

However, unlike the parrot, I don’t just say something: I mean something. This might suggest that, when it comes to my use of language, two processes take place. But where does this second process – that of meaning something – occur?

More here.

While the dramatic breach of the Edenville Dam captured national headlines, an Undark investigation has identified 81 other dams in 24 states, that, if they were to fail, could flood a major toxic waste site and potentially spread contaminated material into surrounding communities.

While the dramatic breach of the Edenville Dam captured national headlines, an Undark investigation has identified 81 other dams in 24 states, that, if they were to fail, could flood a major toxic waste site and potentially spread contaminated material into surrounding communities.

A

A If you could soar high in the sky, as red kites often do in search of prey, and look down at the domain of all things known and yet to be known, you would see something very curious: a vast class of things that science has so far almost entirely neglected. These things are central to our understanding of physical reality, both at the everyday level and at the level of the most fundamental phenomena in physics—yet they have traditionally been regarded as impossible to incorporate into fundamental scientific explanations. They are facts not about what is—“the actual”—but about what could or could not be. In order to distinguish them from the actual, they are called counterfactuals.

If you could soar high in the sky, as red kites often do in search of prey, and look down at the domain of all things known and yet to be known, you would see something very curious: a vast class of things that science has so far almost entirely neglected. These things are central to our understanding of physical reality, both at the everyday level and at the level of the most fundamental phenomena in physics—yet they have traditionally been regarded as impossible to incorporate into fundamental scientific explanations. They are facts not about what is—“the actual”—but about what could or could not be. In order to distinguish them from the actual, they are called counterfactuals. The inspiration for

The inspiration for  You observe a phenomenon, and come up with an explanation for it. That’s true for scientists, but also for literally every person. (Why won’t my car start? I bet it’s out of gas.) But there are literally an infinite number of

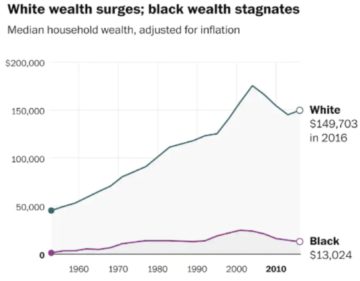

You observe a phenomenon, and come up with an explanation for it. That’s true for scientists, but also for literally every person. (Why won’t my car start? I bet it’s out of gas.) But there are literally an infinite number of  To mark 100 years since the Tulsa Massacre, President Biden

To mark 100 years since the Tulsa Massacre, President Biden  H

H A research team from the University of Massachusetts Amherst has created an electronic microsystem that can intelligently respond to information inputs without any external energy input, much like a self-autonomous living organism. The microsystem is constructed from a novel type of electronics that can process ultralow electronic signals and incorporates a device that can generate electricity “out of thin air” from the ambient environment. The groundbreaking research was published June 7 in the journal Nature Communications.

A research team from the University of Massachusetts Amherst has created an electronic microsystem that can intelligently respond to information inputs without any external energy input, much like a self-autonomous living organism. The microsystem is constructed from a novel type of electronics that can process ultralow electronic signals and incorporates a device that can generate electricity “out of thin air” from the ambient environment. The groundbreaking research was published June 7 in the journal Nature Communications. In 2013, a philosopher and ecologist named Timothy Morton proposed that humanity had entered a new phase. What had changed was our relationship to the nonhuman. For the first time, Morton wrote, we had become aware that “nonhuman beings” were “responsible for the next moment of human history and thinking.” The nonhuman beings Morton had in mind weren’t computers or

In 2013, a philosopher and ecologist named Timothy Morton proposed that humanity had entered a new phase. What had changed was our relationship to the nonhuman. For the first time, Morton wrote, we had become aware that “nonhuman beings” were “responsible for the next moment of human history and thinking.” The nonhuman beings Morton had in mind weren’t computers or  Gilles Demaneuf is a data scientist with the Bank of New Zealand in Auckland. He was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome ten years ago, and believes it gives him a professional advantage. “I’m very good at finding patterns in data, when other people see nothing,” he says.

Gilles Demaneuf is a data scientist with the Bank of New Zealand in Auckland. He was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome ten years ago, and believes it gives him a professional advantage. “I’m very good at finding patterns in data, when other people see nothing,” he says. Thirty years have passed since journalists were cut off from Punjab, and Punjab from the world. In June of each year, Sikhs throng to gurudwaras to observe one of the most significant of their religious holidays. On this day, when even the less observant find their way to gurudwaras, the Indian Army attacked Darbar Sahib—the Golden Temple, the Sikh Vatican —and dozens of other gurudwaras across the state.

Thirty years have passed since journalists were cut off from Punjab, and Punjab from the world. In June of each year, Sikhs throng to gurudwaras to observe one of the most significant of their religious holidays. On this day, when even the less observant find their way to gurudwaras, the Indian Army attacked Darbar Sahib—the Golden Temple, the Sikh Vatican —and dozens of other gurudwaras across the state. Nations, like individuals

Nations, like individuals In a recent study

In a recent study